Cityscape of early modern architecture 1916-1934

‘Städte bauen heisst mit dem Hausmaterial Raum gestalten’ Albert Erich Brinckmann, Platz und Monument (1908)

The educational hand of the SDAP

Reformers of the Liberal Union before World War I

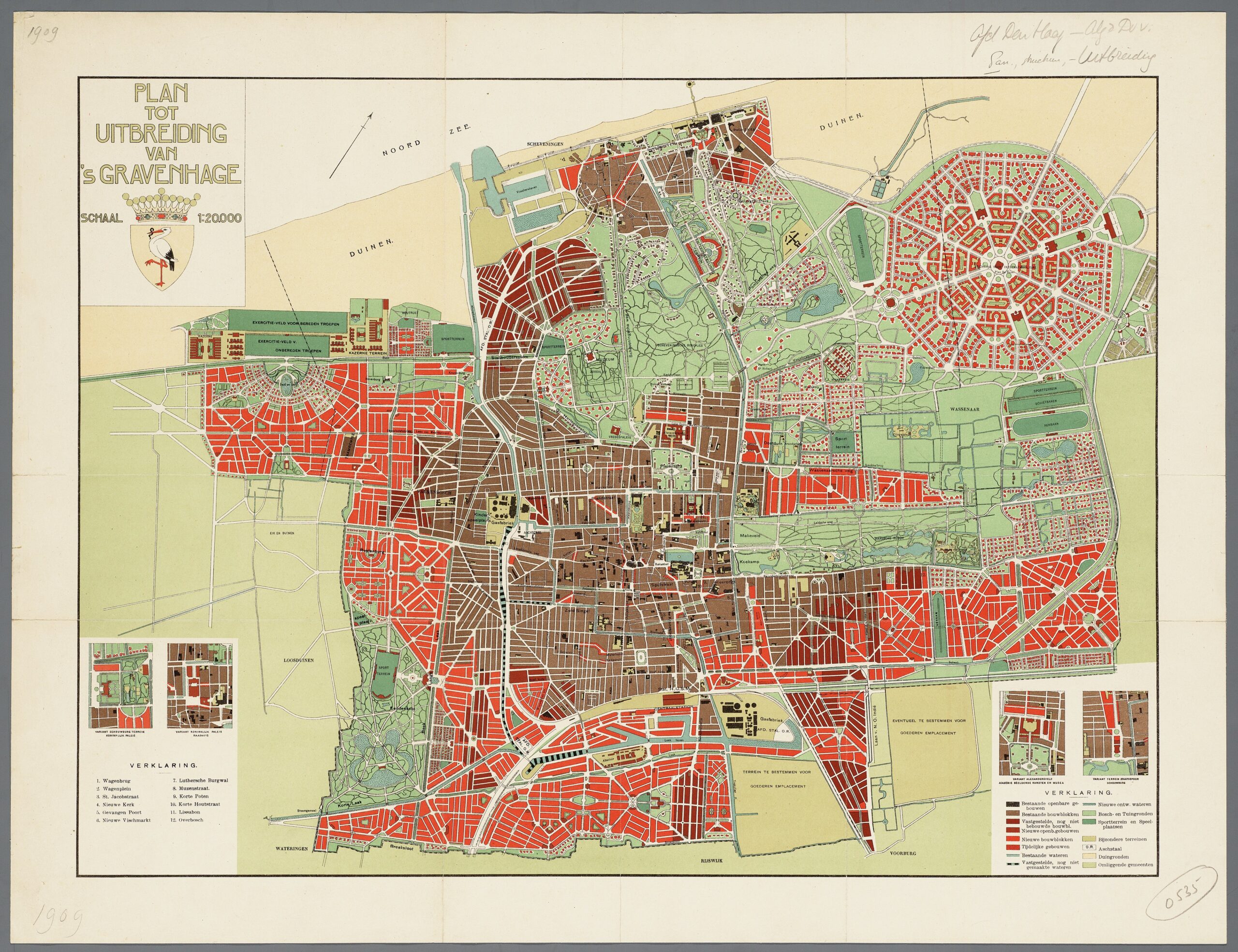

The Hague experienced significant growth during the period between the two World Wars, particularly from 1916 to 1928, resulting in an influx of new residents. In 1914, The Hague had a population of 301,847, which increased to 344,624 in 1918 and 504,262 in 1940. Over the span of 1914 to 1940, the city gained 200,000 inhabitants. From 1917 to 1927, there was a notable increase in the construction of association houses by new housing associations. The construction of municipal houses reached its peak between 1917 and 1927, with approximately 800 homes built per year in the peak years of 1921, 1922, 1923, and 1924. The peak years for construction were 1921 (approximately 620 homes), 1922 (approximately 600 homes), 1924 (almost 700 homes), and 1925 (1,000 homes), with 1923 being an outlier with only 100 homes built. Another outlier year was 1935, when around 500 homes were constructed (Bakker Schut, 1939).

The Land Company of the municipality experienced significant growth due to various expansions. According to Freijser & Teunissen (2008: 85), the proceeds from ground leases quadrupled during this period. Additionally, the number of homes owned by the municipality and corporations in the new suburbs increased significantly. The housing associations in The Hague had appropriate names, such as: Algemeene Coöperatieve Woningvereeniging, Verbetering zij ons Streven, Volksbelang, Luctor et Emergo, Die Haghe, Patrimonium, De Goede Woning, Nutswoningen, Beter Wonen, Openbaar Belang, Ons Belang, Onze Hulp is in den Naam der Heeren. (Baker Schut, 1939: 232). Names that all breathe the spirit of a new collectivism.

The village’s character and lush greenery along the main roads would be preserved. However, the urban areas and their architecture would undergo changes. The extravagant and vibrant architecture of the late 19th century, which focused heavily on individuality, would be replaced by large residential neighborhoods made of stone and brick with flat roofs (all residential houses would no longer have turrets). In these neighborhoods, it would be difficult to distinguish individual apartments from the overall structure of urban blocks.

Furthermore, the connection between ‘Hausmaterial’ and ‘Raum’ is characteristic, creating a hygienic and compact living environment. In The Hague, this connection is referred to as the ‘Beautiful Unity’ or ‘Schoone Eenheid’ in Dutch. The cityscape of collectivization construction, consisting of brick urban blocks of housing affordable houses in monumental neighborhoods with high densities, was developed between and based on the ideals of equality and commonality cherished by the SDAP party.

This concept, known as Gesamtkunst, as described by Berlage, resulted in the integration of monumental urban spaces, intimate residential squares, plants, and affordable association houses in The Hague’s neighborhoods. The ‘Schoone Eenheid’ was not only concerned with formalistic aspects, but also aimed to achieve hygienic urban planning by ensuring sufficient fresh air and daylight in the homes. Building profiles were carefully recorded and improved over the years. The Hague became known for its double brick blocks with intimate residential squares, which were a response to the severe housing shortages caused by the First World War (Bakker Schut, 1939).

The Liberal Union made significant progress in urban development and housing, which led to the implementation of the Housing Act (1901-1902). This was an important first step. Another major step was the expansion plan by Berlage in The Hague in 1908. However, this plan was not put into action due to a lack of land and finances. The ambitions with Berlage’s plan were no more than for inspiration. The third step involved the actual implementation of the Housing Act and the expansion plan.

Two important figures in this process were Liberal Union aldermen, Dr. Cornelis Lely (1854-1929) and Jacob Simons (1845-1921). Simons served as a councilor from 1895 to 1913 and as an alderman for finance from 1904 to 1913. Lely had a diverse background, having been a member of the House of Representatives, a minister, and a governor in Suriname. From 1908 to 1913, he served as an alderman of Local Works and Properties and Fishing Port in The Hague. The completion of the ideal of affordable and hygienic housing for everyone in the new city was entrusted to Piet Bakker Schut and the red aldermen from the interwar period.

Alderman Simons, a member of the Liberal Union, founded the ‘Gemeentelijke Credietbank’ (1914-1921), which later changed its name to ‘nv Bank voor Nederlandsche Gemeenten’ on 24 January 1922. After becoming an alderman, Simons also became the director of the ‘Association of Dutch Municipalities’ (VNG). The bank provided advances and loans for the purchase of land and the construction of affordable housing. Another alderman from the Liberal Union, Lely, emphasized the need for actual funds to be allocated in order to implement the housing law. Additionally, Lely introduced the concept of leasehold, which laid the groundwork for the land policy of the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDAP) during the interwar period.

SDAP hegemony in the interwar period

On December 12, 1917, the municipal secretary of The Hague announced the introduction of universal suffrage for men and the right for women to run as candidates. In the 1918 House of Representatives elections, all men were granted the right to vote and the proportional representation system was implemented, replacing the district system.

This resulted in a significant victory for the confessional Roman Catholic State Party RK and the SDAP. The SDAP supported Article 23 of the constitution, which granted freedom for special education, in exchange for women’s suffrage from the confessionals. The Liberal Union and Free Liberals suffered major losses.

In the 1919 local elections, women were allowed to run for office and be elected without voting themselves. Later that year, they were also granted the right to vote, and in 1922, they were allowed to vote themselves. In The Hague, the SDAP emerged as the major winner, leading to the rise of red aldermen in cities like Amsterdam (Wibaut, Monne de Miranda), Rotterdam (Heijkoop), and The Hague (Drees, Vrijenhoek).

Young politicians like Willem Drees (1886-1988) and Kornelis ter Laan (1871-1963) emerged in The Hague. Ter Laan served as a municipal councilor in The Hague from 1905 to 1914 and was also a member of the House of Representatives from 1901 to 1914. Drees, on the other hand, was a member of the Hague city council from 1913 to 1941 and held positions as an alderman and party leader of The Hague SDAP from 1919 to 1933. After 1933, he entered national politics.

The SDAP and the confessionals prioritized control and influence over society, leading to a strong focus on public housing and urban planning. This marked the end of fifty years of free enterprise and laissez-faire urban development. The devastation and disorder caused by the First World War, as well as the severe housing shortage, likely played a role in this shift. Consequently, a turbulent period commenced for public housing and urban planning in the Netherlands.

After 1919, the typical reflection colleges of The Hague appeared in the municipality, which continued with a varying composition until 1939. The Social Democrats, along with the ‘confessional’ parties: Roman Catholic State Party, Anti-Revolutionary Party, and Christian Historical Union. The ‘liberal’ group consisted of the League of Free Liberals, Liberal Union, Liberal Democratic League, and Freedom League (from 1921). In the 1919 elections, the SDAP had 14 seats, the confessional parties had 16 seats, and the liberals had 9 seats. The three Liberal parties decreased from 26 to 9 seats. In the 1923 elections, the SDAP had 13 seats, the confessional parties had 19 seats, and the liberals had 8 seats. In the 1927 elections, the SDAP had 14 seats, the confessional parties had 18 seats, and the liberals had 9 seats.

This resulted in 2 alderman posts for the SDAP, 2 posts for the confessional parties, and 1 post for the Liberals. For the SDAP, the most important criterion for participating in a college was the leasehold. The large-scale implementation of the Housing Act ambitions was entrusted to Bakker Schut. After the significant election victory in 1919, the SDAP’s hegemony would be complete, and Bakker Schut would solely focus on implementing the Housing Act.

During the interwar period, the Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP) held significant power. Several individuals within the party played crucial roles, including Piet Bakker Schut (1877-1952), who took over from Lindo in 1919 and became the director of the newly established Department of Urban Development and Housing. Another important figure was Dr. Hendrik Enno van Gelder (1876-1960), who served as a party ideologue, lawyer, cultural official, museum reformer, and archivist. Dr. Hendrik Petrus Berlage (1856-1934), an iconic architect, acted as a special advisor to the College of The Hague. Dr. Willem Drees (1886-1988) served as an alderman for social affairs and later public works, while Machiel Vrijenhoek (1884-1947) held the position of alderman for public works.

According to the SDAP-members, the municipal government had to accept a strong leading role (Buschman & Sman, 1994). This responsibility was given to Bakker Schut, who acted as a central figure in coordinating various aspects. Drees, through his tact, managed to maintain the coalition of SDAP, Liberal Union, and confessionals in the city executive and council of The Hague between 1919 and 1933, ensuring the continuation of the land policy. In the last two years leading up to 1933, Drees was involved in public works.

Vrijenhoek, an architect specializing in housing, became a city councillor in 1919. He served as an alderman for public works from 1923 to 1933 and again from 1935 to 1941. Vrijenhoek was well acquainted with The Hague and its new developments, having received his education at the Academy of Visual Arts and Technical Sciences in Rotterdam and the Teekenacademie in The Hague. He also worked at the Hague office of Broese van Groenou and De Clercq. Vrijenhoek attended numerous international conferences on public housing and urban planning, where he gained insights into the latest advancements in the field.

Some other notable architects from The Hague who played significant roles were Jan Wils (1891-1972), Co Brandes (1884-1955), and later Dirk Roosenburg (1887-1962).

The goal of the SDAP was to improve the living conditions of the urban population living in slums and courtyards in The Hague and Scheveningen. They aimed to provide them with better housing, promote a sense of community, and strengthen the bond between individuals. This was particularly important due to the housing shortages caused by the migration flow from Belgium during the First World War.

The SDAP believed that the individualism and laissez-faire of bourgeois society were responsible for the problems in the city during the nineteenth century. The SDAP’s main policies included land policy with leasehold, which allowed the municipality to carry out their ambitious housing projects, and a system to finance and secure housing for low-income individuals. The initial groundwork for these policies was done by Liberal Union aldermen Lely and Simons.

Land policy of the Hague SDAP 1919-1933

As mentioned, there were significant problems during the First World War. These included: (a) a lack of affordable land for building; (b) a lack of funding for housing law housing; (c) a shortage of raw materials and workers, making housing unaffordable; (d) uncertainty regarding who would build the affordable houses, whether it would be the municipality or housing associations.

In 1911, Lely became the first to implement the leasehold scheme and argued that housing law houses could only be built with additional community funding. Aldermen such as Jurriaan Kok, Droogleever Fortuyn, and Vrijenhoek continued to carry out the leasehold.

In 1916, the problems were mentioned again in a publication called The Building Ordinance and the Housing Issue (De bouwverordening en het woningvraagstuk) by Dirk Egbert Wentink (1867-1940), who was an architect and inspector of public health. This book was a collection of articles from the period 1911-1912 and 1914 that had appeared in the monthly magazine ‘De Gemeenteraad’.

Wentink argued that the building ordinance was hindering the improvement of public housing. He believed that the requirements for land use should include the placement of buildings in relation to the public road, the placement of buildings in relation to each other, and the height of buildings. According to Wentink, the provisions in the Housing Act that should have been included in the Building and Housing Ordinance were as follows:

- Governments were allowed to provide subsidies to recognized housing associations and construction companies that worked towards the development of proper public housing.

- Municipalities were now required to create a building and housing ordinance that contained regulations for new buildings, particularly residential homes. These regulations stated that no construction, renovation, or expansion could take place without a municipal building permit. Homeowners were also obligated to perform certain maintenance tasks.

- If a building was poorly maintained, the municipality had the authority to declare it uninhabitable. In cases where the owner neglected their responsibilities, the municipality could even expropriate the property or clear it.

- Municipalities were mandated to create expansion and zoning plans, and these plans had to be reviewed every ten years.

- Municipalities with a population of over 10,000 or a growth rate of 20% in the last five years were required to expand.

The issue of land had to be addressed and the use of land had to be resolved. Lindo also made this argument, but was not listened to. This problem was at the core of the matter: the interests of building-land-companies that could freely speculate and drive-up land prices in beautiful neighborhoods. It was generally believed that land policy needed to be regulated by the government, but nothing was done. With these publications, Wentink outlined the problems that the SDAP faced and implicitly formulated the party’s program during the interwar period, which included municipal land purchase, construction of municipal or association houses, and the leasing of land. A revolving fund would finance urban development.

The main principle of the land policy was that leasehold was the standard, and land could only be sold in special circumstances. Land that had been purchased was then reissued on a leasehold basis after houses were built. Leaseholders were required to pay an annual ground rent to the municipality, and after 75 years, the land would revert back to the municipality. This leasehold system allowed the municipality to generate income, which could be used to help finance housing and other facilities.

This was made possible through the establishment of a revolving fund for affordable housing, thanks to the financial organization at the ‘Association of Dutch Municipalities’ (Vereniging van Nederlandse Gemeenten) by former alderman Simons from The Hague. In 1914, Simons founded the ‘Gemeentelijke Credietbank’, which later became the ‘Bank voor Nederlandse Gemeenten’ in 1922, providing loans to municipalities for financing housing projects. Thanks to the efforts of Lely and Simons, affordable housing during the interwar period became a reality in The Hague.

The Hague had very few opportunities to expand because it was surrounded by neighboring municipalities. However, at the beginning of the twentieth century, this changed and the municipal boundaries were significantly expanded (Everts, 1918). On December 31, 1900, 252 hectares of Rijswijk were added to The Hague. On December 31, 1902, 666 hectares of Loosduinen were also added, followed by another 508 hectares of Wassenaar and Voorburg on July 16, 1907. In total, The Hague became 4,171 hectares in size. In 1923, Loosduinen was annexed, providing The Hague with a large amount of land for its ambitious plans. Additionally, the municipality of The Hague purchased a significant amount of land in neighboring municipalities through a private law arrangement, although it required cooperation to make use of it.

In 1909, the Municipal Land Company was established. A map from 1913, included as an appendix to this book, shows the plots of land that the municipality of The Hague had already purchased in Loosduinen and Voorburg, in addition to the plots within its own municipality. It appears that the land company, under Lely and Lindo, acquired a substantial amount of land in neighboring municipalities (Gelder H. , Jurriaan Kok, Lindo, Stoffels, & Zuylen van Nyevelt, 1913).

In addition to a lack of money, land, expensive raw materials, and workers, there was also tension in The Hague between Lindo and Berlage. Lindo, who was Berlage’s opponent and predecessor, was given the authority by The Hague politics to judge Berlage’s expansion plan. Lindo criticized Berlage for not considering the landscape and believed that the connections made to the old city through major breakthroughs would ruin it. Lindo presented three options to the council and provided an explanation for each. Ultimately, the council chose option two, which required a more comprehensive plan. Only the main roads and squares needed to be determined in advance, as argued by Sitte in 1889. The details within the main roads would serve as a basis for landowners to focus on, and the municipality had the freedom to approve or reject any deviations. In terms of the aesthetic quality of the buildings, Lindo supported Berlage’s proposal to establish a aesthetic committee. It was decided that the plan would be submitted to the city council in parts, along with comments from Lindo.

In order to buy out private individuals, a significant amount of money was required for practical reasons. This was particularly challenging because, during the second half of the nineteenth century, the city council did not want to infringe upon the rights of private landowners. As a result, the plan was heavily debated between Lindo’s supporters and those who believed in a more detailed planning approach, such as Jurriaan Kok, his predecessor Lely, and the SDAP-member Ter Laan (Boekraad & Aerts, 1991). The debate on the enlargement plan primarily focused on these two extreme positions. There was also a third position from the Liberal Union, which supported the Housing Act and a detailed plan, but was not as extensive as the SDAP’s vision.

Due to a lack of funds and available land, the council postponed the issue and passed a motion stating that they did not want to establish ground rules. The strategy was to let the experts work on concrete plans first and then decide what to do with them at a later stage (Boekraad & Aerts, 1991: 69). With this decision, the municipal council withdrew from the discussion, giving the municipal executive more freedom to act. However, the council’s actions were seen as a delaying tactic to avoid fulfilling the obligations of the Housing Act. Nevertheless, without sufficient land and funds, it is challenging to come up with a comprehensive city plan.

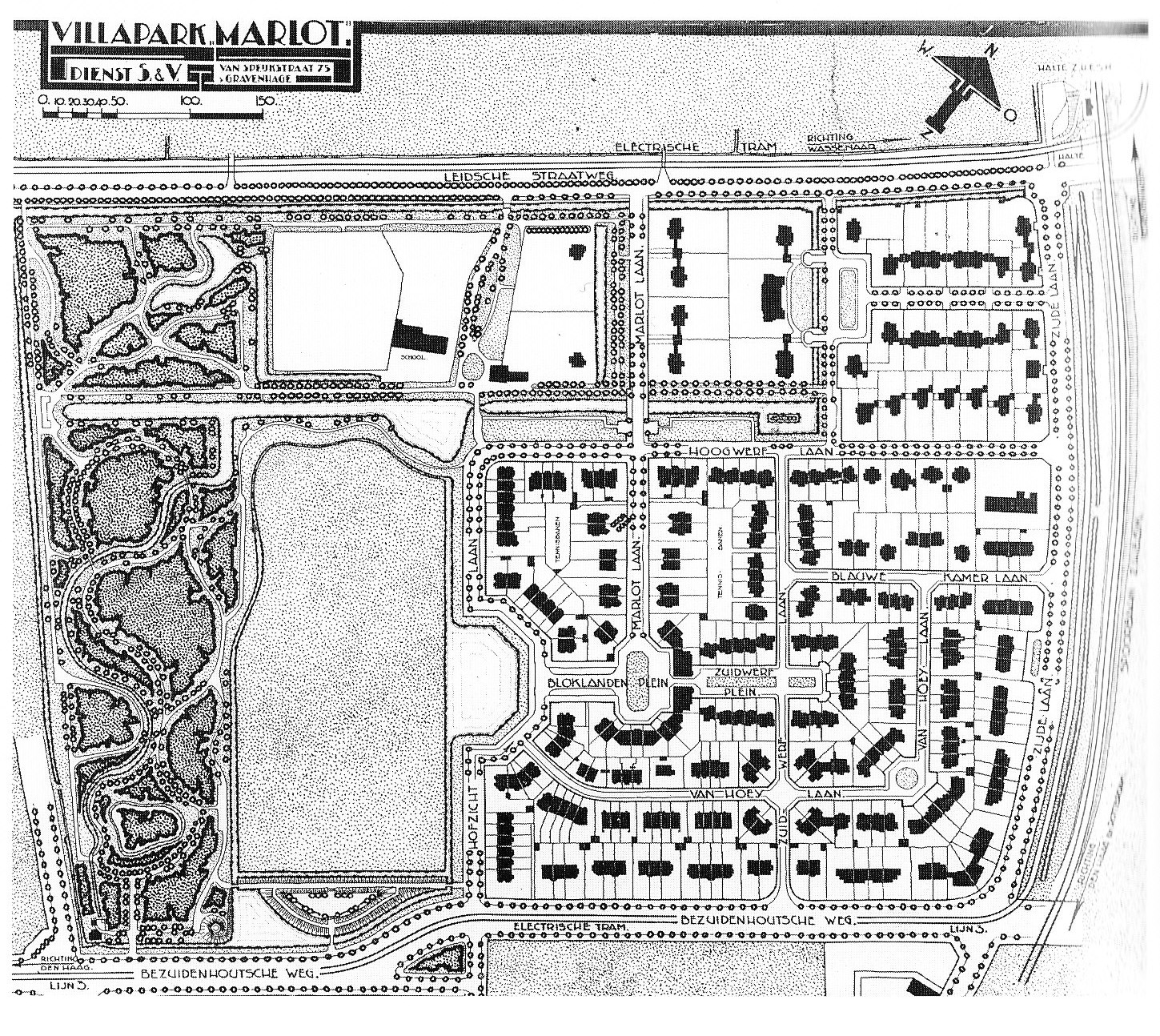

The SDAP took control after winning the 1919 election, which allowed women to vote. Bakker Schut, the new director of the Department of Urban Development and Housing, implemented the SDAP public housing program with his permanent architects starting in 1919. During the period between the two world wars, power and authority were concentrated in Bakker Schut. Starting in 1910, architects were limited by the aesthetic committee, which was tightly controlled by Bakker Schut during this time. Material traders were cut off from the central purchase of building materials by the N.V. Centrale Bouwmaterialen Voorziening (CBV) starting in 1918. Contractors were marginalized by the municipal contractor N.V. Haagsche Bouwmaatschappij (Habo) starting in 1921. Urban planners from outside were excluded by the municipal management through sketch plans that already defined the building outlines, known as the Marlot-method. There were many protests, but opponents were excluded and silenced by arguing that a large number of housing units needed to be built, and contractors’ prices made it impossible (Bakker Schut, 1921) (Leeuw-Roord, 1981).

The architects, The Hague Art Circle and The New Hague School

The Haagse Kunstkring, which was transformed by Berlage and Wils, was a willing body that propagated the ideas of SDAP. Wils played an important role as the secretary of the Department of Architecture and Applied Arts in organizing the exhibitions between 1918 and 1923. He was able to organize various special activities through his contacts with De Sphinx (Leiden Art Association) and De Stijl. Celebrities such as architects B. Taut and E. Mendelsohn, El Lissitsky, mathematician M.H.J. Schoenmaekers, J. Hoffman, J.J.P. Oud, M. Eisler, and F. Schumacher (Deutscher Werkbund) were invited. The permanent members, including Berlage, Huszár, Zwart, Van Doesburg, and Wils, often held exhibitions and lectures there.

The Haagse Kunstkring included not only architects and artists, but also policymakers such as Jurriaan Kok, Bakker Schut, and ir. Henk Suyver, who was an urban planner and deputy director of the Urban Development and Housing Department. Brandes was also involved in club life and in 1918 he founded a magazine called Living Art. When Wils became the editor of this magazine, he had a conflict with Van Doesburg, and as a result, he was only indirectly involved in the De Stijlbeweging movement. The Haagse Kunstkring introduced the innovations of German architecture and urban planning to The Hague.

In 1923, the Amsterdam architecture critic C.J. Blaauw identified and named the ‘New Hague School architecture’ (Freijser & Teunissen, 2008). The New Hague School differed in its composition from many simple affodable association houses and the architecture of Kropholler, for example, which was Bakker Schut’s favorite. However, the architects of both styles shared similar objectives: they aimed to use architecture to bring about societal change (Freijser, 1985) (Freijser & Teunissen, 2008). The simplicity of the brick and the attention to detail brought a sense of unity to this architecture. Additionally, there were many similarities and mutual influences between the New Hague School, influenced by Lloyd Wright and the style movement as seen by Wils and Brandes, and the simple association houses influenced by Kropholler, which Bakker Schut found appealing.

The architecture of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959), who was a contemporary of Berlage, played an important role in the New Hague School. The architects in The Hague became acquainted with Frank Lloyd Wright through Berlage. In 1911-12, he traveled to America and returned with many examples of his new architecture. Jan Wils and Dirk Roosenburg worked at Berlage’s office during the war years. While Berlage had previously been impressed by Louis Sullivan’s projects, his employees were more fascinated by Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1913, Berlage published a booklet titled American Travel Memories. Berlage referred to Lloyd Wright as the most talented architect, but whether he agreed with the new architecture was still uncertain. Eventually, the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague would draw inspiration from Lloyd Wright’s compositions. Its design was characterized by the interplay of horizontal planes and vertical rhythms, similar to the Style movement or the interlocking cubes seen in Co Brandes.

The compositions were often asymmetrical. There were no figurative elements or decorations like in Amsterdam, and the architecture was abstract, strict, and simple. The main materials used were brick and gravel concrete for the horizontal building elements. The masonry surfaces in cubist volumes were also characteristic. Chimneys, eaves, canopies, lintels, and water hammers were used as horizontal and vertical accents. The expressiveness of the building volumes reflected the spatial organization of the buildings, in contrast to the architecture of the affordable association houses in the urban blocks, where the individual houses could not be seen on the façade. Inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, the transition between inside and outside was emphasized with masonry terraces, garden walls, and pergolas. In the New Hague School, the details were proportionate to the whole, and the whole was integrated into the larger space outside the building, expressing a Gesamtkunstwerk.

Three architects, Wils, Brandes, and Roosenburg, played important roles. All three were knowledgeable about international advancements in architecture and urban planning.

Roosenburg traveled to Germany and Italy from 1909 to 1910. He studied at the Technical College in Delft from 1905 to 1911 under Grandpré Molière, where he was taught by Evers and Klinkhamer in classical aesthetics and the Beaux-Arts tradition. The house of Miss H. Luyt on Kerkhoflaan, built in 1918, is one of the earliest and most beautiful examples of Lloyd Wright houses in The Hague. In 1923, Wils, along with J.J.P. Oud, W.M. Dudok, and Mart Stam, was sent to the ‘Internationale Architektur-Ausstellung im Bauhaus’ in Weimar. According to architectural historian Van Bergeijk (1986, 1995, 2002, 2003, 2007), Wils was considered the Dutch representative of modern Dutch architecture. Despite disagreements and conflicts, Van Doesburg recognized Wils in 1920 as a pioneer of cubist architecture and the use of industrial techniques and products. Even before the First World War, Wils visited Germany and Berlin to stay updated on developments.

Brandes returned to The Hague from Germany in 1909. Brandes received his training as an architectural draftsman at the Lotz Architectural Institute, which was an arts and crafts and drawing school in The Hague. He became a member of the Haagse Kunstkring and lived with his friend Willem Verschoor, whom he had met at the Lotz Institute. The school was founded by architect Moritz Lotz, who was the superintendent at Gemeentewerken in The Hague. Brandes then gained practical experience working with Van der Steur, who was involved in the construction of the Peace Palace, among other projects. From 1912 to 1915, Brandes worked with the architects Hoek and Wouters, where he held the position of chief-de-bureau. However, due to the war, the partnership dissolved. In 1915, Brandes established himself as an independent architect in Wassenaar, but he remained associated with Wouters until 1918. In 1911 and 1912, Brandes and Verschoor went on study trips to Berlin, possibly to attend an exhibition on modern German architecture at the Kunstkring in 1910. Brandes’ notable works include the beautiful residential park Marlot (1920/25), the Dalton Lyceum (1934) and the surrounding houses, as well as a large number of other houses. He was the most prolific architect during the interwar period. Bakker Schut apparently saw in Brandes a practical architect who could effectively combine new aesthetics with the concept of serial housing.

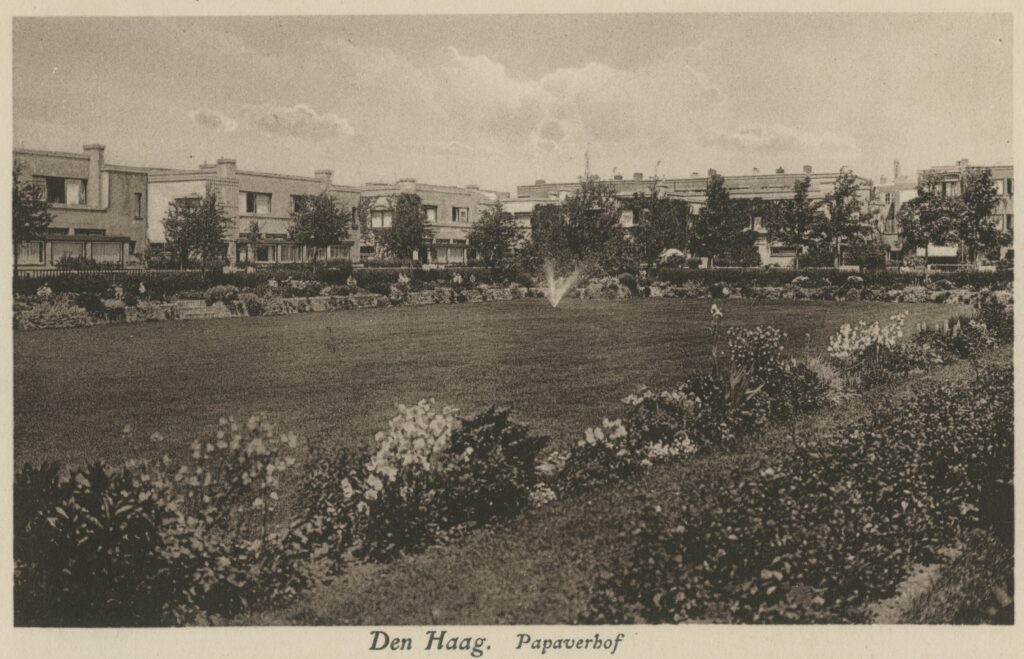

The New Hague School also included architects such as Bernhard Bijvoet, Jan Duiker, Jan Greve, Jo Limburg, Hendrik Wouda, Frans Lourijsen, Henk Wegerif, Cor van Eesteren, and Jan Buijs. Urban planners from the municipality, such as Suyver, Greve, and Alberts, shaped the monumental districts. Marlot vwith an urban plan by Suyver and house designs of Brandes, and Papaverhof van Wils are the most iconic urban ensembles from the interwar period in The Hague.

The aesthetic committee

The cultural policy pursued by individuals like Bakker Schut and Van Gelder on behalf of the SDAP can be best understood by looking at the role and authority of the Hague aesthetic committee. During these years, the committee was responsible for implementing the political ideals through the evaluation of building plans on municipal land. Initially, from 1910 to 1921, the committee only tested building plans, which was already a significant task. However, after 1921, all building plans were subject to evaluation by the committee. Furthermore, the committee also started evaluating expansion plans at a later stage.

Berlage & Lindo

Based on the advice of Berlage and with the support of Lindo, an aesthetic committee was established on July 17, 1910. The committee consisted of four members. One member was delegated by ‘The Society for the Promotion of Architecture’ (later reformed as the BNA), and another member was delegated by the ‘Board of Directors of the Academy of Fine Arts of The Hague’. The remaining two members were appointed by the municipal executive. In the Hague aesthetic committee, it was customary for architects to present their building plans to the committee in sketch form. Only after the committee’s approval, the plans were submitted to the city council for further approval.

The annual reports of the aesthetic committee did not mention the architects who had produced the plans, nor did they discuss the content of the plans. The committee’s standards were not explicitly written down, but they were implied. However, the annual reports did give some understanding of the standards that the committee members used to evaluate the plans. The selection of committee members itself was a decision that reflected the desired image for The Hague.

Initially, the committee members closely followed the ideals of the SDAP party in The Hague, and their powers were consistently expanding. In 1936, the aesthetic committee (Schoonheidscommissie) was renamed the quality committee (Welstandscommissie). However, the architects appointed by the BNA, who were part of the committee, became increasingly disloyal to the political leaders in The Hague. The committee members started to avoid political control more and more. The committee’s aesthetic advice also seemed to hinder the construction of serial housing, which required a certain level of cost-effectiveness. Eventually, all the powers of the aesthetic committee were transferred back to the Urban Development and Housing Department of Bakker Schut, which was the main center of cultural politics in The Hague during the interwar period.

Caring for the cityscape

In 1918, Wils published an article titled ‘De Zorg voor het stadsbeeld’ in which he argues for granting unlimited power of attorney for prosperity. According to Wils, in the past, it was common for regulations to ensure the preservation of a beautiful cityscape, as ‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever.’ However, currently, we are able to provide our cities with good traffic roads, excellent sewerage, street lighting, and even more comfort, but the aesthetic aspect of the cityscape is not being considered. (Wils, 1918: 213).

Wils was not concerned with the committees and regulatory greed that imposed ‘quality’ on the people through a top-down policy. Wils believed that the innate sense of quality in people needed to be developed in schools and made central to education. Wils also believed that quality should become a part of life, a way of being and contemplating. Wils thought that the daily press should also pay more attention to this. Wils expressed sadness that the public is currently fixated on questions of dubious importance that have a short lifespan, and does not notice the ugly house in which they live, a house that does not meet reasonable requirements.

Regarding the aesthetic committees, Wils stated that: ‘For several years, we have been aware of the existence of aesthetic committees in our country. It is unfortunate to observe that these committees have not lived up to our expectations in most cases. This can be attributed to either insufficient instructions or the incompetence of the committee members. Instead of being a driving force for the development of urban beauty, they have had a hindering effect. The effective functioning of a quality commission primarily relies on having unlimited authority. Additionally, the members should be modern artists who are unbiased and have a keen eye for the architectural value of the designs being assessed.’ (Wils, 1918: 215).

Wils was frustrated that architects were not being held to high standards. Anyone was allowed to submit a design for their lunchroom, as long as it met basic technical requirements. Wils believed that if only competent individuals, specifically construction artists, were allowed to design and construct buildings, it would eliminate the need for committees and building inspections. Wils compared this to the situation in Germany, where architects were held to higher standards.

All building plans, 1921

In the year 1921, there were significant changes. The Building and Housing Ordinance of The Hague was modified, and according to Article 94, it became mandatory to submit all building plans. Article 94 was referred to as the aesthetic paragraph of The Hague Building Ordinance. The city council provided instructions to the aesthetic committee regarding the desired cityscape. The committee was established by the new Alderman for Public Works, Mr. P. Drooglever Fortuyn.

The aesthetic committee was also significantly expanded to include nine members and was given its own secretariat. The ordinary members of the committee were divided into three sections, each with its own neighborhood. The city council appointed six members, the BNA appointed three members, and from the official side, the directors were Bakker Schut (urban planning and housing), Westbroek (parks and green spaces), Van Gelder (art and science), J. Lely (municipality works), and G.A. Meijer (building and housing supervision).

The aesthetic committee was given a significant increase in tasks and gained more influence over the built environment. The advisor of the municipality, Berlage, also presented his plans for the breakthrough at the Prison Gate to the committee. It was noteworthy that Van Gelder, a cultural ideologue and museum reformer from the SDAP, was also a member of the aesthetic committee. Together with Bakker Schut and Berlage, the SDAP ideals were effectively implemented in The Hague, as seen in the new buildings. The cityscape was shaped and colored by the process of collectivization. In that same year, alderman Vrijenhoek also took office. The number of meetings increased to 52 per year. In 1921, Jan Wils’ Papaverhof in the Daal en Berg-garden neighborhood was likely discussed in the aesthetic committee, although no report was made of it (HGA bnr 579-01, inv: P4504.0, Annual Report Aesthetic committee 1921).

In a meeting in 1921, the aesthetic committee, mayor, aldermen (Vrijenhoek), and the Commission for Local Works and Property decided to conduct a trial for cooperation. Their goal was to create a building plan for an unsold municipal site in order to improve urban planning. This proposal was made on July 15, 1921. Bakker Schut’s Department of Urban Development and Housing was given the task of developing a building plan for the sites in Marlot. The department then approached architects Verschoor, Brandes, and Hellendoorn to create the building plans. The mayor and aldermen believed that these plans met the welfare requirements sufficiently, so they deemed it unnecessary to submit them to the aesthetic committee. As a result, the aesthetic committee was no longer involved in the planning process.

After deliberation among the chairman of the aesthetic committee, W. de Vriend Jr., the secretary R.C. Mauve, the alderman Vrijenhoek, and the director of the Department of Urban Development and Housing, Bakker Schut, the board made an additional appointment. Going forward, the chairman and secretary of the aesthetic committee will be involved in all discussions between the department and the architects regarding this type of building plan. The chairman and secretary were given access to the preliminary draft and shared responsibility for the success of the final plans.

Architects’ vs politicians

The divide between architects and politicians, which had been present for a while, became evident in 1923. The annual report of the commission in 1923 described a disagreement between the Urban Development and Housing Department and the aesthetic committee. This led to a new contradiction. (Reference: HGA bnr 579-01, inv: P4504.0, Annual Report Aesthetic committee 1923).

According to the 1925 annual report of the aesthetic committee, the college believed it was preferable for the president and deputy chairman not to be architects. Previously, the committee itself appointed these positions, but this rule was changed. In the future, the municipal executive would appoint individuals for these roles, just as they did in the early days of the aesthetic committee. In 1925, the committee held 54 meetings at its peak. However, the goals of the municipality and the aesthetic committee appeared to diverge rather than align. (Reference: HGA bnr 579-01, inv: P4504.0, Annual Report Aesthetic committee 1925).

The stormy development of public housing and urban planning

After Lindo retired in 1918, the Department of Urban Development and Housing was separated from the Department of Municipal Works in 1919. Bakker Schut became the director until his retirement in 1939. Alderman Jurriaan Kok was responsible for initiating this separation. The land department remained a part of the new department. Shortly after, urban planner Suyver and inspector Van Boven joined the team. Architects Pet, Greve, and Albers were already working there. Suyver eventually became the deputy director and would succeed Bakker Schut in 1939.

During the interwar period, Bakker Schut was responsible for determining the urban planning and public housing in The Hague. Previously, matters such as material trading and contracting were not regulated by the government, but now they became municipal services in order to implement the affordable housing project. The municipality of The Hague took the lead in initiating many changes due to political and social pressure. This was largely influenced by the housing shortage following the First World War. Public housing and urban planning became the responsibility of the municipality, and people started to see cities as interconnected. The developments in The Hague were also influenced by cyclical changes and the evolution of the public housing and urban planning profession.

Central Building Materials Supply (CBV) & The Hague Construction Company (Habo)

After experiencing several failed tenders and witnessing building contractors raising prices and potentially making mutual agreements, the City Council of The Hague decided on 18 March 1918 to establish the Central Building Materials Supply (N.V. Centrale Bouwmaterialen Voorziening, CBV). This provision involved the participation of Amsterdam, The Hague, Utrecht, the Department of Water Management, and the ‘Vereeniging van Nederlandsche Gemeenten’ (with former alderman Simons from The Hague). From 1918 to 1921, the central purchase of materials had a positive impact on price developments in the construction industry. Bakker Schut successfully defended against numerous criticisms from entrepreneurs, the liberal camp, and even the timber union (Bakker Schut, 1939).

The timber union declined to work together with the purchasing center, so the CBV was expanded with its own sawmill, planning mill, and carpentry factory. Eventually, the construction prices would decrease to the point where the purchasing center was no longer necessary. However, at the moment, the unity among the contractors and the price agreements they likely had were disrupted (Bakker Schut, 1921).

After the monopoly on material procurement was broken, social democrats such as Drees, Van Deth, Vrijenhoek, and Bakker Schut also took control of construction production from private entrepreneurs. In 1920, Bakker Schut proposed the establishment of a municipal construction company. There was opposition from various groups, but on July 15, 1921, the The Hague Construction Company (N.V. Haagsche Bouwmaatschappij, Habo) was founded (Leeuw-Roord, 1981). This company, owned by the municipality, mainly built affordable housing. The building land was purchased and leased out. The CBV and the Habo played a significant role in implementing collective construction in The Hague, resulting in a high level of construction production (Bakker Schut, 1921) (Leeuw-Roord, 1981).

Subsidy system affordable houses

During the economic boom following the First World War, obtaining long-term loans for housing was expensive. As a result, private housing development was slow, and the government had to provide support and materials for the construction of housing law houses. In 1920, a crisis occurred which caused construction costs to decrease significantly, while wage costs remained the same. This led to the government reducing the rent contribution and eventually stopping it altogether in 1923. By the end of 1920, the government implemented a subsidy system outside of the Housing Act to encourage private construction and housing associations. Advances and contributions under the Housing Act were no longer given after this change.

According to Bakker Schut (1939), the government’s change in attitude had significant consequences for The Hague. Several requested improvements for a total of five thousand homes, such as in Duindorp, Spoorwijk, and Rustenburg, were ultimately not approved. The municipal administration and the ministry extensively discussed the situation that had arisen. In 1922, the Minister responded by stating that the government had concluded that it was not possible to continue providing funds for housing without causing a general disruption of the state finances. Initially, the granting of subsidy for housing construction by municipalities was excluded, but later municipalities were also allowed to apply for subsidies.

According to Bakker Schut, between 1922 and 1925, a new subsidy system was implemented to determine housing production, resulting in the construction of many more expensive homes. Although the old system had been abolished in 1922, it continued to be used until 1925 due to pending and old applications. From 1925 to 1940, the housing market was mostly controlled by private building contractors, as long as construction had already begun after 1930. This information is supported by Bakker Schut (1939), Nycolaas (1974: 38-39), and Smit (1981: 120-124). Bakker Schut also mentioned that sporadic re-application of the Housing Act took place in 1926 and subsequent years (Bakker Schut 1939: 39).

Netherlands Institute for Housing

The developments in the field of public housing and urban planning were stimulated by various individuals, including SDAP-member Dirk Hudig (1872-1934), for several years. These developments eventually led to the establishment of the ‘Netherlands Institute for Housing’ (NIV) in 1918. This organization, which initially focused on public housing, expanded to include urban planning in 1921 and was later transformed into the ‘Nederlandsch Instituut voor Volkshuisvesting en Stedebouw’ (NIVOS) in 1923. Its mouthpiece was the Tijdschrift voor volkshuisvesting from 1920 and the Tijdschrift voor Volkshuisvesting en Stedebouw from 1923.

The Rotterdam architect and professor in Delft, M.J. Grandpré Molière, who gained recognition for his work on the garden village of Vreewijk in Rotterdam-Zuid, became the director of that institute (Baneke, 2008) (Steenhuis, 2009). Bakker Schut also regularly published in this magazine (Stedebouw, 1930). From this organization, the current ‘Nederlands Instituut voor Ruimtelijke Ordening en Volkshuisvesting’ (NIROV) developed. Hudig and others advocated for social science research as the basis for designing expansion plans. They also highlighted many foreign examples of regional and provincial plans and encouraged learning from them. The concept of regional planning from Anglo-Saxon countries gained significant attention at the ‘Internationaal Stedebouw Congres’ held in Amsterdam in 1924.

Bakker Schut was a member of the editorial board and regularly published in this journal and for this institute. Bakker Schut also contributed to the congress in Amsterdam with the publication: ‘The Need for District Expansion Plans in the Netherlands’ (Bakker Schut, 1924). From the beginning, public housing, such as Bakker Schut in The Hague and Keppler, the director of the Amsterdam Housing Service, knew each other from their studies in Delft and the study association ‘Social-Technical Association of Democratic Engineers and Architects’ (STV). This association was founded in 1904. In 1924, the name changed to ‘Social-Technical Circle of Democratic Engineers and Architects’ (STK). The aim was to promote popular prosperity, the growth of the state system in a democratic sense, and to advocate for the social interests of engineers. When it was converted into the ‘Socio-Technical Circle’ in 1924, the association took on a more private character. In 1935, the STK was dissolved (IISH: ‘Archive of the Social-Technical Association of Democratic Engineers and Architects’).

Workers' housing in the Netherlands

The book that was published in 1921, titled Arbeiderswoningen in Nederland – Vijftig met rijkssteun, onder leiding van architecten uitgevoerde plannen, met de financieele gegevens – Bijeengebracht door DR.H.P. Berlage, Ing.A. Keppler, W. Kromhout en Jan Wils (Berlage, Keppler, Kromhout, & Wils, 1921), demonstrated that public housing was not only a concern for public housing administrators and urban planners, but also for architects.

This book was accessible to architects and it provided guidance on how to construct affordable housing with government support. The drawings in the book were all to scale at 1:200, and each plan included information such as the year of construction, the number of homes, the foundation costs, and the weekly rent per home.

The book did not provide a complete overview of the achievements in public housing because not all architects who were contacted had made their plans available for inclusion. In the preface, Berlage stated that the book did not only showcase good examples, but also included poorly designed plans that were built with government support. These poorly designed plans referred to the individual homes in the garden city or garden district. In reality, the book was a compilation of successful examples of collectivization in architecture. Berlage further argued:

‘As a result of this event, the artistic workers’ house, as a separate house in the garden city and garden city district, as a housing block in the city itself, has already found its realization. And that is undoubtedly of such importance that for those who will later write about the development history of contemporary architecture, the workers’ house will prove to be the most important element in this.’ (Berlage, Keppler, Kromhout & Wils, 1921: IX).

Pay close attention to the term ‘development history’. Berlage referred already to Hegel and the history of development when explaining the Hague expansion plan of 1908.

Architect Willem Kromhout (1864-1940) also advocated for a closed cityscape in his contribution to the book. Kromhout argues that the open nature of the city leads to the loss of the enclosed cityscape and the charming picturesque intimacy found in old towns and villages. Kromhout criticizes his contemporaries who transformed old storefronts into the fashionable styles of Art Nouveau and Wiener Secession, drastically altering the appearance of the city.

‘The emergence of a town or village always gave the sensation of picturesque intimacy, … Old towns and villages are therefore natural monuments of special value, the houses, trees, churches and town halls, everything has grown together into an inviting, inward-luring warm cozy whole and rarely can one escape the oppressive wish when walking through the charming streets, squares and canals, oh, if this remains untouched for a long time! Such a wish does not arise without reason, for here and there we see as rudely intervened by the village carpenter or contractor, who, according to dubious city proposal, erects a fashionable storefront there, where formerly a serious, simple building, unpretentious, of the all-round beauty offered its modest share. The study of the causation of the old intimacy of the town and village architecture, as well as of the town and village agglomerate, had not yet begun, now after years foolish in appearances, much has improved, which will eventually also find its repercussions in the not yet too well started villages and small towns.’ (Berlage, Keppler, Kromhout, Wils, 1921: XIV).

Kromhout was annoyed by the abstention of the The Hague municipal government and indecisiveness that resulted in the closure of the old city (Zeeheldenkwartier, Archipelbuurt) and the subsequent enormous breakthroughs made in the old city to address the accessibility issues that had arisen.

‘Especially of the great cities, for rough was the manner in which they made their way through the old circle. …. ; the Hague saw its indecisive perimeter enrichment with the Zeehelden and Archipel quarters. What a pity of unbridled breakthroughs everywhere! Gone was once the beautiful enclosed nature of cities, ………… Streets without end, which showed no tendency to any swing, planless combinations hatched at the then city offices, without any understanding of urban composition.’ (Berlage, Keppler, Kromhout, Wils, 1921: XV)

This remark was actually strange because, despite being the co-author of the book, Berlage drew the straight breakthroughs while Lindo (Grote Markt) and Van Liefland (Gevangenpoort sketches) made efforts to incorporate curves. It is possible that Berlage and Wils should have informed their colleague Kromhout better about the situation in The Hague.

The plans described in the example book from the municipality of The Hague represent the first generation of housing law houses, which were constructed by the municipality and housing associations.

Berlage and The Hague as Gesamtkunstwerk

‘Oh Rome my country, city of soul’ (Berlage, 1909: 2. Berlage quoted Byron as having these words spoken by the literary character Childe Harold).

The city as the most beautiful work of art

The most important insight that Berlage brought in 1908 was the idea that the city should be viewed as one unified entity, with urban space and buildings interconnected. In a dialectic way the old romantic and picturesque landscape, along with the existing buildings, combined with the new classic and monumental figures of the residential neighborhoods, create a new identity for The Hague. An identity where the past seamlessly transitions into the present and future. The use of double building blocks and bricks served as symbolic representations of this concept.

According to him, urban planning is a form of art and people should strive for a total art (Gesamtkunst) where all experiences come together to create a new feeling. This idea, originally proposed by composer Richard Wagner for opera, was supported by Viennese urban planner and theorist Camillo Sitte. Sitte’s textbook, Der Städtebau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen (1889), was highly influential in the field of urban planning. Sitte believed that the city was not just a result of civilization, but also a phenomenon that produced civilization. Similarly, for Berlage, the city was a work of art that condensed the culture of society, including science, art, morality, commerce, politics, and economics. Berlage argued that art is power, and power is art. Like Wagner, the integration of music, poetry, movement, acting, and theater architecture creates a sense of unity and harmony with the audience. This applies to both individualistic individuals and those who feel a sense of community.

In his preface, Sitte (1889) started by acknowledging the progress made in urban planning, particularly in the areas of traffic and public health. However, he criticized modern urban planning for its failure in the artistic aspect, as it had not produced anything significant in that regard. He pointed out that modern urban planning prioritized monumental buildings rather than the spaces between them. Sitte describes these areas as lacking elegance and being poorly designed.

‘…, and opposite the beautiful new monumental buildings are the clumsiest square shapes and subdivisions in the immediate vicinity of the squares.’ (Sitte, 1889: 9).

The Department of The Hague of the Society for the Promotion of Architecture asked Berlage to write an explanatory statement in 1909, which he based on earlier lectures. Berlage discussed Sitte’s book enthusiastically in the Bouwkundig Weekblad. Previously, the city was seen as a collection of street plans created by building-land-companies between existing thoroughfares. Now, the city was seen as a Gesamtkunstwerk. In his detailed explanation of The Hague Expansion Plan (Berlage, 1909), Berlage connected Hegel’s conception with his theory of Romantic architecture, as well as the views of Semper, Sitte’s theory (1889), and Brinckmann (1908). Berlage stated in his explanatory statement that:

‘An aesthetic issue as highly important, but above all social as urban planning, first acquires its special value when it is seen in its historical context and explained in its causal development.’ (Berlage, 1909:1).

Bakker Schut argued that the urban ensemble forms a:

‘very close link between urban planning and public housing. The residential areas should not be made unilaterally in one corner of the city. They must connect to the city in such a way that they obtain good connections with the core, where their own intellectual, spiritual needs can also be satisfied. There, the church, public reading room, bathhouse, association building and the main shopping groups must be built and grouped into a whole. The shape of the building blocks must be such that regular construction can take place: building blocks of unfavorable, unmotivated design give rise to twisted building solutions, to expensive houses with an unfavorable floor plan. The course of the streets can and must be such that monotony in the street scene is avoided without resorting to sought or capricious solutions. A map of a new city district must be clear and logical. The simpler and clearer the map on paper, the easier it will be for the resident to orientate himself in the neighborhood, if it is made of stone.’ (Freijser & Teunissen, 2008: 86).

It was not just about the Schoone Eenheid between buildings and urban space. The dialectic of Hegel, which Berlage refers to in his explanation of the expansion plan, goes much further. It also involved the unity between people and ideals, with the city as a backdrop. Additionally, it encompassed the hygienic ideal of healthy urban planning, ensuring light and ventilation in all homes. The Schoone Eenheid also represented carefully designed building profiles, in other words, modern urban planning.

After years of debate and stagnation, Berlage’s plan was eventually implemented in a general form. In many residential areas from that time, the baroque figures can still be easily identified, although they do not exactly match the original expansion plan.

In 1913, Berlage relocated to The Hague, where he lived and worked until his death in 1934. He served as a special advisor to the municipal executive and the SDAP in The Hague and played a role in shaping the affordable and hygienic houses in the numerous monumental residential neighborhoods of The Hague.

The aforementioned theorist Brinckmann would look back on urban planning and architecture in The Hague with his ‘Architectural impressions from The Hague: I and II’ in Het Vaderland of 24 and 25 July 1919. Although they had similar ideas, Brinckmann was diametrically opposed to Berlage. Het Vaderland was the newspaper owned by Lindo’s uncle Martinus Nijhoff (the poet’s grandfather) and was associated with the Liberal Union. Jan Wils, an architect and colleague of Berlage, also wrote for this newspaper.

The stony garden neighborhoods of The Hague

The garden neighborhoods in The Hague are stony and have a different appearance compared to the greener garden neighborhoods found elsewhere during this time period. This difference can be attributed to Berlage’s vision for the city. As point out, Berlage did not agree with the Anglo-Saxon concept of a Garden City that emphasized abundant planting. In The Hague, the focus was on creating monumental garden neighborhoods that seamlessly integrated with the existing city, rather than building garden cities far outside the city. Berlage opposed those who advocated for the abolition of cities. He did not specifically mention individuals like Howard, Unwin, and Parker. Additionally, he did not mention Letchworth Garden City (1903) or Hampstead Garden Suburb (1906), which were idealistic new towns located outside of London in the English landscape.

Berlage painted an inaccurate picture of the garden city here. On the contrary, the concept of the garden city aimed to capitalize on the benefits of both urban and rural areas while minimizing their drawbacks. However, Berlage expressed a rather negative view without providing specific reasons or thoroughly exploring the ideas. Berlage pointed out that:

‘Not long ago I heard someone whose whole life of thought revolves around popular prosperity proclaim that all cities must disappear. That person was one of those socially tiring people, for whom there is no other than social interference, …’ (Berlage, 1909: 2).

Berlage believed, like Schumacher, that cities were responsible for creating great works of art. He believed that art and power were interconnected, and where there was a lack of art, there would also be a lack of power, and vice versa. Despite Berlage’s dislike for the Garden City Movement of Howard, Unwin, and Parker, several garden neighborhoods with wide parkways were lay out around The Hague and other municipalities during the interwar period. The garden districts were always located within cycling and tram distance of the city.

These included neighborhoods such as Marlot, Meer en Bosch, the Rijswijkse Voorde’s, the Voorburgse Vreugd en Rust, and the Vogelwijk. Originally, the Vogelwijk was called the garden city district Houtrust and Segbroek, and it was developed on the estates that Goekoop had purchased from the Grand Duke in 1903. In 1917, the ‘Coöperatieve Woningbouwvereniging Tuinstadwijk Houtrust’ was founded by individuals such as Van Boven, Hoek, and Verschoor.

The green areas, such as Marlot, have symmetrical structures and a monumental design. This is different from the garden districts and residential parks of the previous generation, like Zocher (Agnetapark in Delft, the never-executed proposal for Willemspark, and Van Stolkpark in The Hague), Coppieter (Belgisch Park), and Mutters (Wassenaar and Rijswijk), as well as contemporaries like Henrici’s villapark (Zorgvliet from 1910), which was partly developed at the same time as the monumental garden neighborhoods.

The picturesque and the monumental united

Berlage’s Expansion Plan for The Hague, developed in 1908 (synthesis), aimed to combine to unite of the old romantic picturesque conditions of nature, geomorphology of the landscape and existing buildings (thesis) with new classically monumental residential neighborhoods (antithesis). According to the Hegelian scheme of thesis with antithesis, Berlage thus came to the synthesis, with this scheme Berlage deviated from Sitte. While Sitte, a Darwinist, saw urban transformations without an automatic link and progression from ‘bad’ to ‘good’. Berlage, influenced by Hegel’s idealist philosophy, believed in the continuous improvement and evolution of society and city towards an ideal organic society. It is likely that Hegel had a significant impact on Berlage’s thinking.

Berlage (1909) explained how the true beauty of old cities comes from united the classical and romantic character, as Hegel had argued a hundred years earlier. He also questioned whether new cities should be built and expanded in a way that reflects the past. He suggested that the regular lay out of classical cities could provide inspiration, while the ideas from the Middle Ages could help solve any unexpected transitions. He stated that:

‘If, therefore, the plans of the classical cities could serve as a reason for the regular lay out, those of the Middle Ages gave the ideas to the solution of accidental transitions. In this way, therefore, the spirit of the plan could be kept in classical conception, while the natural conditions provided the picturesque factor, thus a beauty in a romantic spirit. Thus, therefore, the material bequeathed to us in the construction of the old cities could be used not as imitation but as a reason, to its full extent, and to ensure that the forcedness in both directions, both in classics and in romantic spirits, was avoided.’ (Berlage, 1909: 24).

However, it was necessary to examine the existing buildings and the landscape. In Berlage’s expansion plan, the existing buildings are represented by dark brown color, the new buildings are represented by red color, and the surrounding landscape is carefully indicated. According to Berlage, in order to truly appreciate the beauty, we must study the history of cities. The classical urban planning of Greece had a predetermined plan and a preference for regular construction and straight streets, which was also adopted by the Romans. Hegel considered this to be a symbolic art. According to Hegel, romantic urbanism is mainly Germanic and Christian, and it is based on organic growth. Villages were initially founded for economic reasons and gradually grew into cities without a predetermined plan. Berlage, following Hegel, states that Greek cities had a classical character while medieval cities had a romantic character (Berlage, 1909: 8).

Berlage quoted Hermann Muthesius (1861-1927), who also believed that there were two periods of brilliance in Western culture: ‘ancient Greece and the Nordic Middle Ages.’ In 1904, Muthesius introduced English architecture and urbanism to the continent and played a significant role in establishing the first German Garden City, Hellerau, outside Dresden in 1909. Martin Wagner, a socialist city planner and pupil of Muthesius, later laid out large-scale Garden Cities around Berlin between 1924 and 1932. According to Berlage, both forms of architecture were characterized by distinct but opposing spiritual worldviews. Berlage then translated this contradiction, as used by Hegel and Muthesius, into the contradiction he employed as: ‘monumental’ versus ‘picturesque.’ According to Berlage, the relationship between the monumental and the picturesque must lead to beauty. He also states that the monumental, being stylized, is a higher form of beauty. Therefore, choosing between these two directions should not be difficult (Berlage, 1909: 14).

Berlage observed that the old part of The Hague had a naturally organized street grid lay out, with streets running at right angles to each other. This principle was then used as the guiding principle for the expansion plan. Specifically, the streets parallel to the beach walls were well-developed, while the streets perpendicular to the beach walls were somewhat neglected. These streets often had irregularities and did not follow a straight path, which eventually became problematic for car traffic. The essence of The Hague’s expansion plan was that these were fragments of monumental plan parts, which were connected in a romantic and sometimes accidental way (Van Rossem, 1988) (De Klerk, 2008).

The reason why not all neighborhoods were the same was because of various factors, including the geomorphology of the landscape, the existing buildings, and the random development of residential neighborhoods in the past.

‘The ideas developed in the previous lecture were now also the guiding ideas in the design of the expansion plan of The Hague. They led to the principle of regularity, i.e., not of painfully retained symmetry, but of a regularity to which the cities of antiquity, but especially those of the Baroque era, developed. By maintaining such ‘obstacles’, a certain monotony is automatically avoided, which is probably inevitable when a fully regular plan is implemented. The consequence of such a development was the emergence of a system of regular plan sections, which had to be connected by chance, i.e., in the intended sense. This method of partial grouping was also facilitated by the many street plans already laid down by a Council decision, which was generally felt to be an obstacle to the design.’ (Berlage, 1909: 24).

The double urban blocks and brick as a symbol of collectivity

The Schoone Eenheid between buildings and urban space took its most pronounced form with the double urban block with an intimate residential square for social interaction that were built between 1916 and 1922. Urban spaces and brick housing thus acquired a characteristic cohesion within the monumental residential neighborhoods. The desired collectivity was thus brought among the drifting sand of the city dwellers, it was thought.

The double urban blocks were most likely first constructed in Akroyd Model Village in Halifax, England, starting in 1863. This model village was built by Akroyd, a textile manufacturer (Smit, 1981: 124). It became a popular concept among Social Democrats. In red Vienna, between 1927 and 1930, the Karl-Marx-Hof was built as a fortified urban block with its own internal world. Berlage’s expansion plan from 1908 already included several proposals for double urban blocks. Berlage argued in explanation of the expansion plan, echoing Brinckmann that:

‘Because if ‘urban planning is creating space with the housing material‘, then it is clear that with the inadequacy of the material, the space will also be difficult to satisfy. And this difficulty is certainly not diminished for urban planning in the Netherlands, because the relationships here in the country are generally limited. For wide straight streets, in order to create space in the aforementioned sense, also require corresponding means, i.e., a monumental architecture, both in character and in size.’ (Berlage, 1909: 25).

Also, in Berlage’s 1915 Plan Zuid for Amsterdam, there are double urban blocks. These were not present in Berlage’s 1904 plan for the south. The design for the Spaarndammerbuurt in Amsterdam from 1912 by J.M. van der Mey included these double urban blocks. In 1919, architects De Bazel and Walenkamp designed and built two beautiful double urban blocks in Zaandammerplein and Zaanhof.

Similar ensembles can be found in The Hague, such as Duindorp or Molenwijk, characterized by simple solid masonry and pitched roofs. Many of these buildings have been demolished due to urban renewal efforts. However, there are still double urban blocks with intimate residential squares in The Hague, including Windassraat, Meeuwenhof, Gagelplein, Weigeliaplein, Moerbijplein, Vlierboomplein, Schaapherdersstraat, and the most famous one, Papaverhof. The double urban block concept aimed to create a new relationship between green spaces, affordable houses (with fresh air and sufficient daylight), and various types of squares.

The double urban block had a disadvantage in that it took up a lot of space, which made it difficult to achieve the desired number of houses. This is likely why they were only occasionally used in the layout of new neighborhoods. Having a whole city filled with double urban blocks would be invaluable. The architects and urban planners of the municipality were primarily responsible for implementing the double urban blocks with affordable houses of the associations, although the neighborhoods Papaverhof and Marlot were exceptions to this.

Berlage and his followers believed that the symbol of honesty and collectivity was the brick. They saw it as a typical Dutch material that could be used to build a house without any embellishments or unnecessary decorations. In his essay Reflections on architecture and its development, Berlage, influenced by Cuypers and De Bazel, advocated for the use of brick (Berlage, 1911).

‘The unity in the multiplicity of the brick, that multicolored ness of the yellow by comparing the reddish to violet tones, in their range with that of an autumn forest, created by the way in which a brick wall is constructed, makes the operation of the brick unsurpassable. In addition, the decoration, the sophistication of a brick architecture lies in the material itself.’ Berlage argued. ‘The brick,’ Berlage ordered, ‘which as a single person is a nullity, as a mass a power, is the example of the equal social image to which it has to give color and form. Every profile, every formal peculiarity, every expression of whimsy perishes in the tone of the masses, of the whole. Isn’t that socially speaking? Does that not mean that the individual must submit to the whole? Does not brick-building, in such a view, invent the democratic idea, which is growing, the idea, which leads materially and therefore spiritually to generalization? … It may even be said that modern architecture in the brick possesses a material best suited to its mode of expression: it is the essence of contemporary conception of architecture to strive for the style of objectivity, which seeks to develop its charms through the purely businesslike, as practical as possible, solution to the eternal question, on the way one divides and groups, not how one decorates and decorates. So back to the brick.’ (Quote from Berlage 1911, from Freijser & Teunissen, 2008: 37).

In June 1912, the Dutch Association of Brick Manufacturers organized an exhibition of brick at the building of the Society for the Promotion of Architecture (BNA). They stated: ‘This exhibition is very interesting not only for the craftsman, but also for the layman. After all, it was not so long ago that many Dutch architects used materials other than brick for their preference. It was Cuypers and Berlage who changed this.’

The exhibition was accompanied by a competition, which aimed to demonstrate that a house could be built using brick at a relatively low cost. According to a newspaper report, a cast house in Santpoort cost no more than f 2,000, so the challenge was to build a rural house of brick that did not exceed f 2,200. There were over 120 entries, and the first prize was awarded to Willem Verschoor, the second prize to Jan Wils, and the third prize to A.J. Rinsberg, all of whom were young architects from The Hague region.

The new monumental residential areas of 1916-1928

In the first phase, the buildings and urban spaces in The Hague were closely connected and formed cohesive urban ensembles. Some of these ensembles, such as Papaverhof and Marlot, are still considered iconic from the interwar period. Interestingly, the only part of Berlage’s expansion plan that was fully implemented was the Bomenbuurt, which was developed by the building-land-company Duinrust of Goekoop. A map from 1915, which includes the building plans, illustrates the relationship between the buildings and urban spaces (HGA z.gr.1324).

In this first phase, small neighborhoods were mainly built within the network of main roads. These neighborhoods include Bomenbuurt, Duindorp, Molenwijk, Trekweg (today Laakkwartier Noord), Spoorwijk, Bloemenbuurt, and Bohemen. They consisted mostly of three-storey buildings. There were also more open garden city districts with many detached houses, such as Houtrust, Segbroek (later renamed Vogelwijk), and Marlot. Later on, some through roads were located within the districts, such as Laakkwartier, Moerwijk, Rustenburg, Oostbroek, Leyenburg, and during the large expansion in The Hague West. The baroque figures can be recognized in all these districts. In the interwar period, the municipality and housing associations also worked for years within the street plans from Lindo’s time. This was seen in parts of Schilderswijk-Zuid, Benoordenhout, Bezuidenhout, and Transvaalkwartier.

The residential areas were characterized by brick architecture and uniform height, resulting in a brown pancake-like appearance. The neighborhoods consisted of double blocks with apartments and quiet residential squares, reflecting a sense of collectivism and contrasting with the previous period’s neighborhoods.

The urban spaces, such as courtyards or front gardens and residential streets with gates the ends, were intimate in nature. Individuality was stripped away from homes, as the façade did not indicate the size of the apartment or the status of its residents.

Instead of emphasizing individual houses, the focus shifted to the level of the urban block, where individual apartments merged into a collective. Typically, four to six apartments shared a common external staircase, and it was preferred that they no longer had their own front door on the street. Apartment buildings had flat roofs, while ground-level family homes had pitched roofs. Public buildings often had pitched roofs to highlight their presence.

The austere brick architecture of this period did not include any references to the history of the people or the country, or the latest fashions from Paris and Vienna. Through the construction of collective buildings, members of the SDAP aimed to create a unified identity and image that expressed equality among people. The best plans incorporated various international influences, particularly those of Frank Lloyd Wright, the style movement, and cubism. This style of architecture later became known as the New Hague School (Freijser & Teunissen, 2008).

Jan Wils’ Papaverhof was an exception among the urban ensemble in The Hague. Unlike the prevailing brown buildings, Papaverhof stood out with its white color. It was a beautifully designed double building block with intertwined floor plans, allowing for maximum utilization of light and air. This project also aimed to explore the use of concrete in residential construction, following earlier experiments in Scheveningen before 1916. Various techniques were tested to achieve increased and affordable construction production. However, it was discovered that wood was a much cheaper material, both during the tendering process for the first part of Duindorp and at Papaverhof (Kuipers, 1987).

Traffic and monumentality

The new neighborhoods of The Hague were like self-contained villages within the extensive network of roads, waterways, and tramways. However, this concept started facing challenges with the increasing presence of cars. The Expansion Plan for Laakkwartier (1922) aimed to address this issue by transforming the main street, Goeverneurlaan, into a significant axis that would provide coherence to the neighborhood, similar to the Expansion Plan of Amsterdam-Zuid. As a result, Laakkwartier ceased to be just a village within the infrastructure network and became an integral part of it. It is interesting to explore the ideas of Wils and Berlage regarding this transformation.

In 1919, Jan Wils delivered a lecture titled The Freestanding Monument in the Modern Cityscape for the Haagse Kunstkring. In this lecture, he discussed a new theory. The lecture focused on two concepts, ‘picturesqueness’ and ‘monumentality’, which were already used by Berlage in his explanation of his expansion plan in 1909. Wils also described a visit he took with Berlage to Brussels and Leuven.

‘For a few weeks I had the pleasure of walking with Dr. Berlage successively through the streets of Brussels and Leuven. Both cities will be known to the majority of you, so that you can follow me there in your mind. In Brussels, we were hit again for the umpteenth time in the vicinity of and also the Parc-Leopold, by the grand design, the pure construction, the management of the situation, the ability to take sides with and introduce new factors to this end, creating a cityscape with a – I do not say ‘monumental’ yet – which impresses us by greatness of operation. And shortly afterwards we were in Leuven, went on the canal along the Dijle, along the Begijnehofje. This neighborhood of Leuven has not suffered anything because of the fire. It is difficult to say how we were moved by the sight of those little houses, plastered white with their red roofs, a tree every time, as all that stood with its foot in the water, quiet and forgotten, as if no man ever came again. If we had not known, it would have become clear to us that we. The Dutch, we felt more strongly about the picturesqueness than by the monumentality. It is not a result of reasoning, but was cool and calm to observe reality. The Dutchman feels nothing of monumentality, on the other hand he sees everything in color: the Dutch architect is more painter than master builder, the Dutch nature is more attuned to picturesqueness than to monumentality. Our cities, with their whole construction and in their entire construction, are there to prove that it has always been so. Does it still make sense, like this evening, to talk about ‘monumentality’ and ‘monuments’?’ (Wils 1919)

Wils adhered to Brinckmann’s previously mentioned quote and starting point. According to the lecture, Berlage also returned with Wils to the concept of ‘reconciliation’ (synthesis) in the expansion plan, which aimed to balance ‘picturesqueness’ (thesis) and ‘monumentality’ (antithesis).

The reason for this was the significant increase in traffic, which had already resulted in a completely different street plan in other countries. The old villages and towns in Holland also gradually adapted to the new situation, which was unavoidable. However, Wils argued that our cityscape should also meet aesthetic standards. People believed that having ‘decorated squares’ or ‘show-off streets’ was sufficient to enhance the city, but Wils believed that more was needed. It was about creating and organizing the entire street system, comprehending the construction of the building masses as a whole.