Cityscape of Fin de Siècle 1890-1905

‘überall Schema, keine Eigenart’ Josef Stübben, Der Städtebau (1890)

The call for beautification and urban amenities with the Liberal Union

Lindo and Van Liefland and the experience of modern times and space

The contrast could not be greater with the previous cityscape. The cityscape of the fin de siècle would produce picturesque neighborhoods like villages with a diversity of buildings full of ‘Eigenart’ within the ‘Schedule’ of wider streets with the first cars and trams. A feast of materials, colors and shapes, for squares and through streets, make these residential areas very popular. Fin de siècle means in French for the end of the century. If one sees a turret on a house somewhere, it is usually a fin de siècle district where individuality was noisily celebrated. The neutral village in the leafy greenery with its actual village character with the new housing estates was given a new layer with great image quality. Due to the way of urban interpretation with building-land-companies, new residential areas were mainly built within the network of main roads, which further strengthened the village character. The cityscape of the fin de siècle was made possible by advancing industrialization and profound social changes. The political climate after 1890 changed and prosperity increased among a large part of the bourgeoisie. Individual expression and experiential value were central to The Hague until 1910. The call for quality such as diversity, individuality and hygiene in the city resonated with the Liberal Union with affordable technical facilities implemented by a completely new service. A new architecture and new social values.

A number of legislative changes accelerated the arrival of this cityscape. The Netherlands received the first Patent Act (Octrooiwet) in 1817, but this law was abolished in 1869. This law was considered too restrictive. In 1883, 140 countries agreed on patents, trademarks and designs in the Paris Union. An inventor had the right to apply for a patent within 12 months. It would take until 1910 before a National Patent Act was passed. So, there was no good legislation on the patent during this period, which gave a lot of freedom to developments.

The Liberal Union also abolished the patent law tax system (Patentrecht) in 1884. That was a professional tax, a precursor to corporate tax. This gave one the right or license to carry out a business or profession. In 1813 the Right to Patent was introduced. After the constitutional revision of 1887, a much broader faction of middle-class men was allowed to vote. The Census suffrage 1849-1887 was transformed into Universal Suffrage. All men who owned or tenant a house with a rental value above a certain minimum were now allowed to vote. As a result, the Liberal Union became the main party. In the city council, the interests shifted and that was also reflected in the city’s facilities, which were being implemented at a rapid pace. The abolition of patent law and the absence of patent legislation started a true revolution in building materials and construction techniques. These legislative changes had a major impact on society.

They also looked at the world from a whole new perspective. The fin de siècle was accompanied by a change in the experience of time and space. Albert Einstein’s 1905 special theory of relativity did not stand alone. There was a huge technological development. In this period, with a new mobility and infrastructure works, telegraph and telephone, the experience of space became different. Naturally inspired by examples from the major European metropolises. The space itself was reduced because people were in another city faster than ever with the new mobility that developed during the second half of the nineteenth century such as train, steam tram and later electric tram, the first cars. In other cities one saw historic architecture that one also recognized in one’s own city.

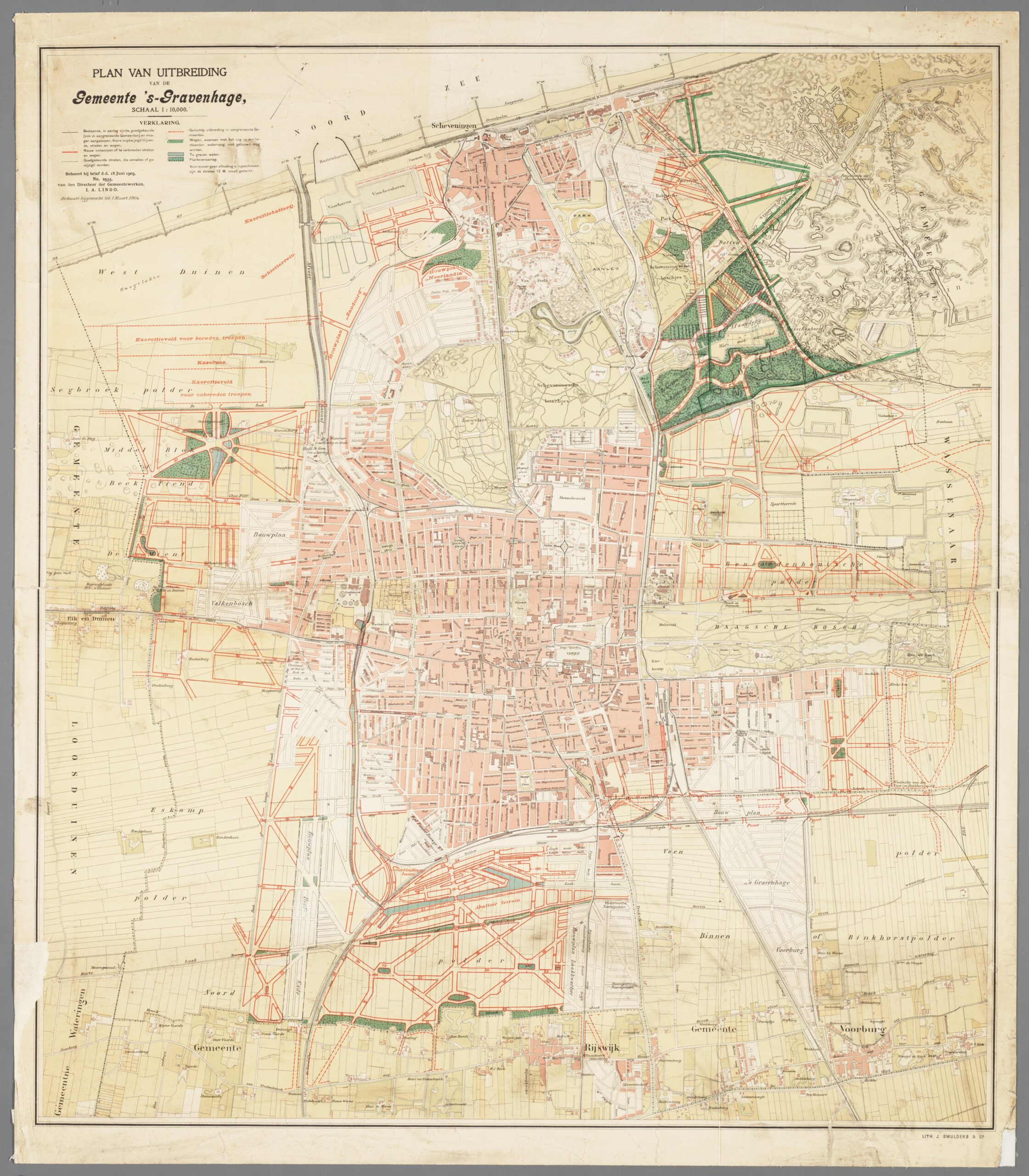

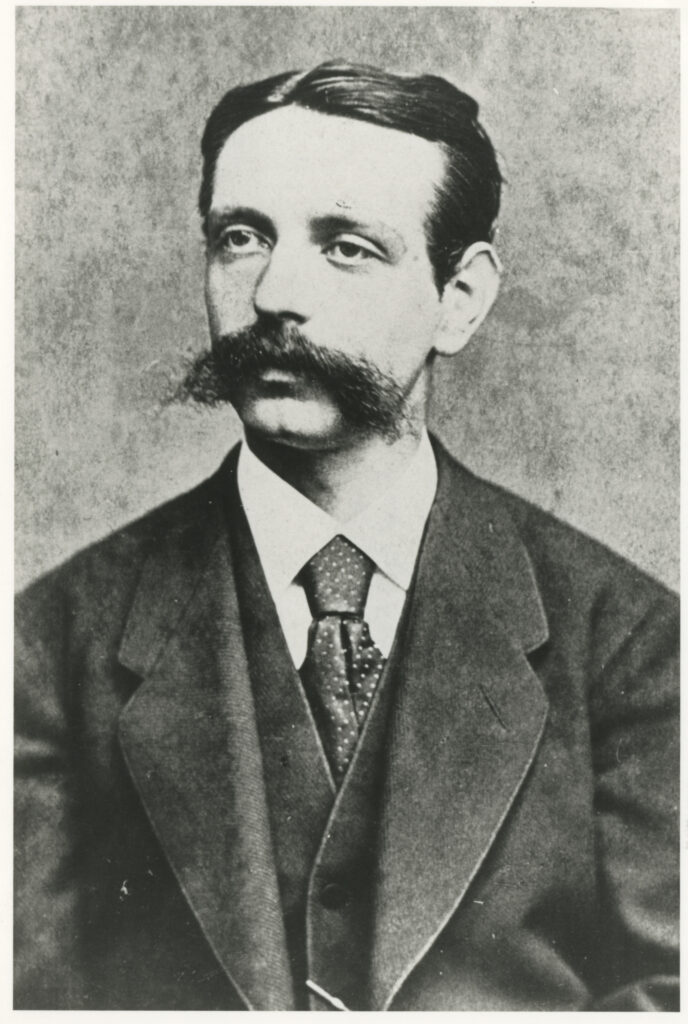

Who were the important people in this cityscape? Diversity and individuality were seen as beauty and quality. While Lindo had an eye for beauty and quality, Van Liefland had an eye for urban planning, technology and politics (he was also a council member). While Lindo, in his expansion plan in 1903, was accused of not having an understanding of beauty. Both found each other in different plans such as those for the Transvaalkwartier and the Bezuidenhout, and in the breakthroughs in the city center where they preferred the picturesqueness of crooked streets to the straight boulevards of Halbersma and eighteen years later Berlage and alderman Lely.

The quote from the German urban planner Josef Stübben (1845-1936) from 1890: ‘überall Schema, keine Eigenart’, in which traffic circulation played an important role and the diversity of buildings arose naturally due to all the small initiatives, was music to the ears of the progressive liberal Lindo and architects such as Van Liefland. The same applied to the pleas of the Viennese urban planner Camillo Sitte (1843-1903) for the experience of urban spaces such as in the picturesque medieval cities with a diversity in buildings and enclosed urban spaces (Sitte, 1889) (Reiteren, 2003). The Hague aldermen of the Liberal Union, such as Jacob Simons (1845-1921), also Dr.ir. Cornelis Lely (1854-1929) and Jurriaan Jurriaan Kok (1861-1919), administrators who also played an important role in the creation of the Housing Act (1902) and the Berlage Expansion Plan (1908), considered quality, diversity and individuality important.

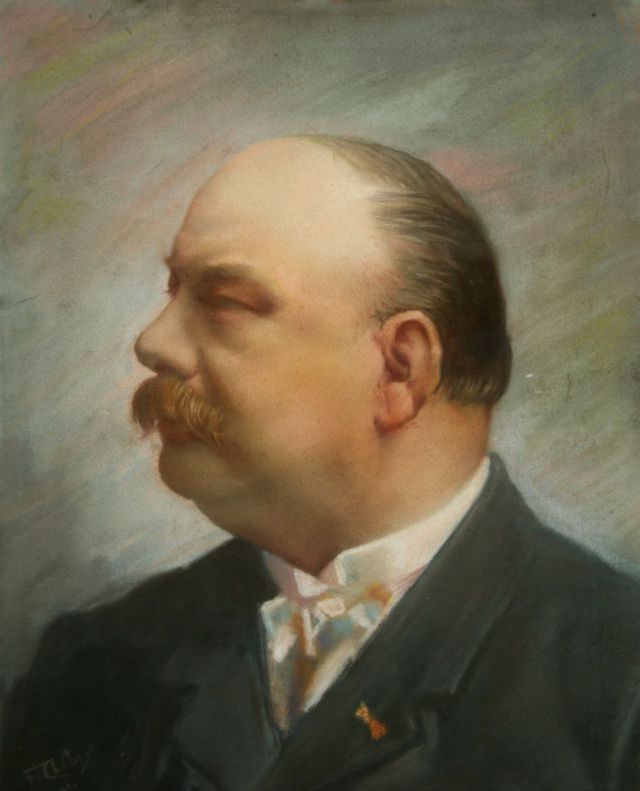

The seaside resort was the most iconic urban ensemble. European-oriented architects such as Van Liefland and the firm Mutters (which would carry out the ship carpentry for the Titanic) gained name and fame during the substantial expansion in the seaside resort from 1893 to 1904 under the visionary leadership of Bernhard Goldbeck (1844-1921) of the Maatschappij Zeebad Scheveningen (M.Z.S.). The plan that Van Liefland made in 1902 for the seaside resort was a novelty. The hotels, the walking head, the promenade along the beach, the circus theater and other buildings were meticulously mapped out and all available building plots were clearly visible. Just before the great Second Peace Conference in 1907, this was an attractive urban ensemble to invest in. The painter Sommer produced two enormous panoramas of Van Liefland’s plan for the management of the Exploitatie Maatschappij Scheveningen (E.M.S.), the successor of the M.Z.S. The seaside resort would prove invaluable and a catalyst in the development of the new cityscape. It attracted many wealthy new citizens who settled in the residential parks.

The city center also went through a stormy development. Everywhere, old facades were demolished and replaced by huge glass fronts supported by ornately curved wood and cast iron. The Hague turned into a real service city with ministries, offices and luxury warehouses and shops with open glass facades. Around the Piet Heinstraat, Hoogstraat, Wagenstraat and Spuistraat many beautiful shops appeared with fin de siècle facades.

The cityscape also found its way into the new residential areas. The historical consciousness with neo-Renaissance architecture was not forgotten either. Neighborhoods such as Duinoord and the Statenkwartier with the beautiful avenues and beautiful squares with richly decorated houses were iconic urban ensembles for The Hague. For example:

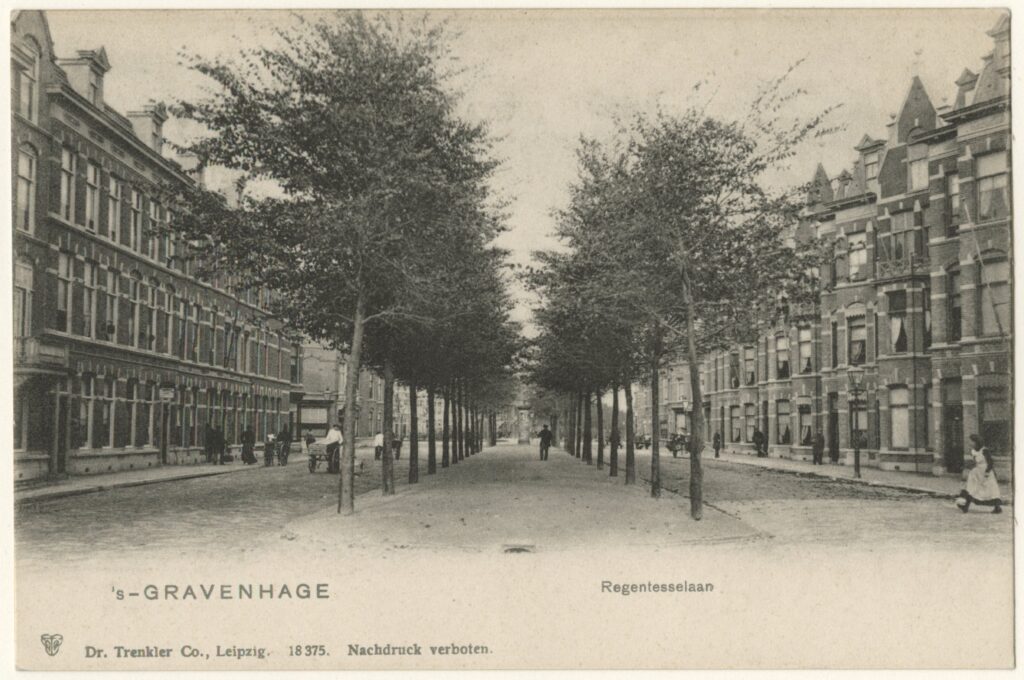

- Regentessekwartier (Regentesselaan);

- Duinoord & Groot Hertoginnelaan;

- Transvaalkwartier (Paul Krugerlaan, Schalkburgerstraat);

- Statenkwartier (Statenlaan, Stadhouderslaan, Eisenhouwerlaan, Willem de Zwijgerlaan, Frederik Hendriklaan);

- Valkenboskwartier (Valkenboslaan);

- Schilderswijk Zuidwest (Vailliantlaan, Van der Vennestraat, Ruijsdaelstraat, Wouwermanstraat, Zusterstraat);

- Bezuidenhout (Juliana van Stolberglaan, Louise de Colignystraat, Stuyvesantstraat);

- Benoordenhout (Bilderstraat);

- Belgisch Park (Amsterdamsestraat, Middelburgsestraat);

- Renbaankwartier (Renbaanstraat).

Between 1890 and 1910, turrets of all shapes and sizes appeared everywhere on residential houses and retail warehouses, The Hague truly became a turret city. Internationally oriented clients and owners of building land companies made this urban development possible. The Hague land trader and building contractor dr.mr. Adriaan Eliza Herman Goekoop (1859-1914) and The Hague banker and entrepreneur Dr. Daniël François Scheurleer (1855-1927) supported cultural life and saw that quality was a necessity to interest new residents in buying a house in one of their new neighborhoods. These fin de siècle districts consisted of a system of continuous closed urban spaces with a wide variety of small-scale buildings of mostly three to four floors. No closed building blocks but open corners for daylight and ventilation, no homes in courtyards. The separate and more expensive houses on main roads and squares were given individuality. Houses were usually built by construction companies in series of two to ten pieces.

This cityscape has clear characteristics. In experience of modern times and space, various aspects played an important role. These aspects became the characteristics for these urban ensembles of Lindo, Van Liefland, Scheurleer and Goekoop, among others:

- Mobility facilitated with a traffic circulation with continuous system of main streets, roads and rails;

- Hygiene through utilities, light and air for the houses with open building blocks;

- Diversity in buildings due to different angles between streets;

- Individualization of more expensive homes on main streets and squares;

- Closed urban space due to kinks, curvatures, dead ends of streets, constrictions at the beginning and end of residential streets;

- Greenery in urban spaces (such as central strips with shell pavement and double rows of trees near the main streets and front gardens in the residential

The cityscape of the fin de siècle is the most complex and the most elusive, but one with a huge influence on The Hague. There is no fixed body of thought that can be referred to, rather it is a tough undercurrent. It has no unambiguous form and no discourse. The cityscape of the fin de siècle did acquire its own character that distinguished itself sharply from the period before 1890 and after 1910. On the basis of the building plans, the conflicts and especially the circumstances, the cityscape of Lindo and Van Liefland cum suis can be reconstructed. The Hague distinguished itself from other cities of this period and thus acquired a distinct individuality.

During the fin de siècle, the experience of the individual in the fields of urban planning (Sitte, 1889) and housing became important. When designing urban spaces, it was preferable to look through the eye of the space users instead of applying an abstract grid. Serial homes were given their own expression or at least their own front door. From 1890 it mattered what a city or a house looked like and this became a task for the urban planner and architect who shaped it, just like with the picturesque Van Stolkpark.

Aestheticization, historicization, individualization and Universal Suffrage

The Liberal Union is one of the most important institutions, played an important role and dominated the House of Representatives and the Council of The Hague. In the cabinet of social liberal Nicolaas Gerard Pierson (1891-94), between 1892 and 1893, the tax system was radically reformed from a system based on paying taxes on goods to a system that was also based on taxes on wealth and taxes on income from business and profession. Also, as previously reported, patent law and patent law came to an end. As a result, economic development was stimulated considerably and industrialization kicked into high gear with major consequences for the building culture. The change in the tax system gave the state and the municipalities more financial opportunities (Smit 2002). The deplorable state finances in 1840 were no longer in question around 1900. It put an end to the financial animosity between the provinces and reduced the political and social divisions, because the tax received many more taxpayers after the reforms (Smit, 2002).

The Department of Municipal Works grew into an important institution that shaped the lay out of the infrastructure. Together with large investments by bankers Goekoop and Scheurleer such as at the seaside resort and the new residential areas. Lindo was the right man in the right place. He had the political tide with him, because the progressive Liberal Union wanted to get rid of laissez-faire. After the reorganization of the Department of Municipal Works in 1890 and the arrival of the first director architect Isaac Anne Lindo (1848-1941), the lay out of urban ensembles was professionally taken care of by architects and engineers.

Lindo was a versatile engineer with experience in the field of waterworks, trams, roads and street plans. In Arnhem he had shown that he had an eye for urban beauty and the new ideas in the field of urban planning and hygiene. Engineers worked at a rapid pace on urban facilities such as sewers, utilities, streets, streetcars and waterworks. In 1905, the civil engineer Pieter Bakker Schut (1877-1952) would be hired by Lindo to take care of the electrification and lay out of the tram network. As early as 1907, Bakker Schut was promoted to Ingenieur-Afdeelingschef. From 1891 onwards, architects of municipal works such as Adam Schadee (1862-1937) built schools, police and fire stations, bathhouses, wash houses, slaughterhouses and buildings for the utilities such as the gas factory and the electricity works on a large scale.

Other architects such as Bernhard van Liefland (1857-1919) brought the new architecture and taste from London, Paris and Vienna to The Hague and renovated Scheveningen Bad. The East Indies also attracted the attention of architects, residents and shopkeepers and beautiful tile panels, onion towers and horseshoe arches appeared everywhere on houses and at shops. All these entrepreneurs, architects, engineers knew each other and worked together on the city.

Bourgeois culture broadened with the attention to history, individualization and aestheticization in this heyday (Bank & Buuren, 2000). The literary movement such as De Tachtigers (ca.1880-94) and the painters of the Hague School proclaimed a new art with impressionism and naturalism. In The Hague, the internationally oriented Berlage and the journalist Johan Gram (1833-1914) had been fulminating against the monotony of the neighborhoods for some time (Gram, 1893, 1906). For Berlage this was an outgrowth of individualism and lack of direction by the municipality, for Gram the boring construction company houses that were built everywhere. The artistic and intellectual milieu of The Hague was concentrated around a number of institutions and persons of prestige and influence, often also the persons who were directly involved in the lay out of the neighborhoods and the buildings. A lot of preliminary work had already been done by artists of the Hague School from 1847 in the Pulchri Studio, especially under the chairmanship of banker and painter Mesdag.

For example, the Historical Society Die Haghe (Geschiedkundige Vereniging Die Haghe), which was founded in 1890, united The Hague’s cultural elite of bankers, entrepreneurs, administrators, journalists, architects and civil servants. Honorary members included Gram, Baron Snouckaert, Scheurleer, Goekoop, De Stuers, Israëls and Mesdag. On the board were Goekoop and Gram. Van Liefland, Molenaar, Mutters, Van Nieukerken and Simons were also mentioned as working members in 1898. The architect Wesstra was also a member, as an extraordinary member were also called the banker Penn and De Sonnaville. These were almost all the people in The Hague who were involved in the seaside resort, the lay out of neighborhoods and the buildings between 1890 and 1910. These individuals concentrated power, money, land, influence, and vision. The society had the Grand Duchess of Saxony, Princess Sophie of the Netherlands and the Queen Regent Emma as main donors. Article 1 of the association’s statutes, when it was founded on 15 December 1890, read: ’to get to know and know the history of The Hague from the sources.’

A year later in 1891, another important association was founded: The Hague Art Circle (De Haagse Kunstkring). Initially, the art circle was a movement around Jan Toorop (1858-1928), Johan Thorn Prikker (1868-1932) and his Arts & Craftswinkel on the Kneuterdijk and Henry van der Velde (1863-1957) who brought Art Nouveau, Jugendstil, Wiener Secession and the new art to The Hague. Jan Toorop organized the first retrospective of Van Gogh in 1892. The differences between the camps within the art circle grew larger and larger over the years and the movement gradually politicized itself with Berlage and Wils. Architect members were: Cuypers, Berlage, Wils, Brandes, De Bazel, Wijdeveld, Van der Kloot Meyburg, Wegenrif, Broese van Groenou, De Clercq, Gratama, Stuyt, Jurriaan Kok and Bakker Schut. In 1923 Kurt Schwitters and Theo van Doesburg held the first Dada meeting in the Netherlands in the The Hague art circle.

With Pulchri Studio, Geschiedkundige Vereniging Die Haghe and De Haagse Kunstkring, all the main players who contributed to the aestheticization, historicization and individualization of the city are together. The cityscape of the fin de siècle was self-evident to them. The previous period seemed completely forgotten.

Changes to the inner city and the new residential areas

After 1870, the civil and workers’ quarters described above started the process of phenomena that would later be referred to as ‘suburbanization’ and ‘city formation’. City formation, a term Gram already used, is a complex process. As described earlier, the old dark residential city with its smelly canals turned into an illuminated service city with ministries, restaurants, beautiful warehouses, bazaars, shops like lanterns and walking areas with shell pavement and lime trees in the places of the muffled canals. The sweet-smelling linden blossom had softened the malodorous scent of the canals in the summer.

Around 1870, the population within the canals reached a maximum of more than 60,000, about 65% of the population, then the population in the center decreased. In 1880 there were still 56,000 inhabitants. In 1900 the city center still had 55,000 inhabitants and in 1910 only 52,000 inhabitants, 11 to 12% of the population disappeared from the old center (Bakker Schut, 1939) (Stokvis, 1987). The city changed from a place where people lived and worked (which often still took place in one building) to a city where shops, fashion warehouses, offices and ministries dominated. Rising rents and ever-rising land prices drove people from the attractive parts of downtown to the edges. Stokvis (1987) argued that the municipality even promoted this exodus from the center with its ideas about breakthroughs and remediations. For example, on the spot where one of the oldest parts of The Hague was located, the old buildings were demolished and the Haagse Passage was opened in 1885, a development that was exemplary for this period (Knibbeler, 1986).

Old-town bourgeoisie who could afford it preferred the new neighborhoods, without smelly canals, with the luxury of housing with drinking water and sewers. The inner city of The Hague transformed into two zones: on the one hand the service city in the most beautiful places and on the other hand the slums, where the population remained who could not afford to move to the new neighborhoods. Here there was decay and poverty (Gram 1893). The stench of the canals that functioned as open sewers also played an important role in the departure of the wealthy citizens from the city center, despite the fragrant lime trees in the summer.

In The Hague, the fact that between 1890 and 1910 the national administration and the ministries were considerably expanded. But the achievements of industrialization also played a role in these changes in the city (Lintsen et al., 1992-94, 2005).

The new residential areas and the service city became closer together because of the steam trams (all lay out between 1879-1887) and because of the finer network of horse trams and later electric trams, but especially because the bicycle came into use by the general public. Connections to other cities by steam tram lines and railway lines also became shorter in travel time. In general, the city was increasingly divided into functional zones such as residential areas, industrial zones along the water and the railway tracks, and the service sector in the center.

Between 1890 and 1910, The Hague changed from a small industrial city to a civil service city with new ministries and luxury retail warehouses and residential areas outside the canals, a process that began around 1870 with the lay out of the new districts. There was a whole new relationship between travel time (living-working), travel costs, means of transport and land price. Between 1886 and 1911, the city doubled in size and population, the municipal budget tripled, and the number of students in schools doubled. In the journal De Ingenieur, Lindo (1911: 70-75) compared these years:

| 1886 | 1911 |

Number of inhabitants | 138,696 | 274,263 |

Municipality area | 2.754 hectare | 4.171 hectare |

Municipal budget | fl. 2,950,000 | fl. 10,759,000 |

Pavement area | 1,109,000m2 | 3,400,000m2 |

Municipal schools | 30 | 82 |

Number of pupils | 9,900 | 22,700 |

Special schools | 47 | 66 |

Number of pupils | 7,500 | 15,400 |

Several eyewitnesses noted this transformation in the city and described it in visual language (Gram, 1893, 1906) (Brunt, Het huis in de Gortstraat: Kind in Den Haag, 1977). As a little girl, Nini Brunt (1977) lived in the old center at Gortstraat 19 (a narrow side street of the Spuistraat) where her father had a bookshop. Together with her sister, father, mother and maid, they lived in a house that has now been demolished. Brunt described the crowded city, the shops, the poor and rich streets and the exodus to the new neighborhoods, which was accompanied by an increase in status. She moved with her family to the new Zeeheldenkwartier, the Heemskerckstraat, then a barren and stony neighborhood. The house and shop on the Gortstraat turned into a warehouse after the family left and later the house was demolished and replaced by a luxury store warehouse. About changes in the city, Gram wrote that:

‘Think of those thousand valuables, redundancies, and jewels, caressed and weary by a brilliant illumination, twinkling and radiant, luring and delighting you. Imagine the eager and admiring gazes of those countless, gently advancing guests, who have no eyes enough to take in all those glories. A sea of light, all radiant against a bright background.’ (Grams, 1906: 162).

He further commented on the transformations in the city that:

‘The ‘CITY’ of The Hague is the Groenmarkt with the adjacent Hoog-, Veene- and Spuistraten. There is the heart of the flaneurs world, there are the large warehouses of fashion and gallant items. Especially the Spuistraat has made surprisingly large toilets in recent years. Mirror glass, shiny copper and giant displays lure the passer-by. Lampe’s mantle palace surpasses the sparking mirror glasses of its competitors in space, richness and size of display. And especially in the evening, hundreds of gas burners and electric flames increase the value of competition. The Spuistraat then resembles a ballroom … with a very mixed audience. A later invention, the second-hand sales houses, a kind of Bazars, are brought together by anyone who wants to put their household goods, antiques or works of art for sale. The largest of this kind is Maison Drouot in the Lange Houtstraat.’ (Grams, 1893: 26).

The new fashion warehouses and stores were designed according to the latest fashion in leading European cities. Between 1890 and 1910, The Hague city center became a European-oriented city with beautiful suburbs outside that were easily accessible by tram and bicycle.

The engineers of the Liberal Union and the Berlage expansion plan 1908

With a broad faction of the bourgeoisie at the helm, the political spectrum also changed. The Liberal Union (1885-1921), founded in 1885, became the most important and largest party in the Netherlands and in The Hague. The Liberal Union was a federation of local electoral associations that stood for broadening the right to vote. Between 1890 and 1918 there were four cabinets with the Liberal Union. Many administrators and civil servants from this period in The Hague were members of this party or sympathized with it. In The Hague, Jacob Simons, Cornelis Lely and Jurriaan Jurriaan Kok were aldermen for the Liberal Union. Lindo was also a progressive-liberal and according to his diary he voted for Jurriaan Kok.

Lely, Jurriaan Kok and Lindo belonged to a generation of engineers who consciously wanted to shape society (Lintsen, 2005) (Baneke, 2008). The Liberal Union was an alternative to the anarchist-tinged Social Democratic League (SDB) of 1881 and the Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP), which split off from it in 1894, which developed into a more reformist and parliamentary party. The Liberal Union fought for the freedom of the individual, but at the same time it was for the protection of the weak. Together with the Free Liberals they formed the Pierson cabinet (1897-1901).

Positions included a limited role of the government, taxation according to ability to pay, good social insurance laws, universal suffrage and suffrage for women, improvement of the position of women, introduction of a people’s army, public education and (from 1908) a system of proportional representation. Because of new laws such as the Housing Act, the Compulsory Education Act and the Accidents Act, the Pierson cabinet was called ’the cabinet of social justice’. For the more progressive liberals and social democrats, these developments were still too slow, mainly because, according to them, real social justice was not possible without universal suffrage. Three aldermen of the Liberal Union in The Hague were given a major influence on what The Hague would look like and how the housing law should be applied: Simons, Lely and Jurriaan Kok.

Jacob Simons (1845-1921) was Alderman of Finance incl. Taxes and Verification (1908-1913). This Jewish businessman, friend, colleague and client of the architect Van Liefland played an important role in the development of a financing system for housing law homes. Simons and Van Liefland knew each other from the council and from building-land-companies in which they both participated (Creveld, 1999). The shifting of assignments between Lindo, Van Liefland and Simons in the development of the Bezuidenhout and Transvaalkwartier suggests that Lindo also had good relations with Van Liefland and Simons. As director of a building-land-company, Simons was involved in the development of the Bezuidenhoutkwartier: between Laan van NOI, Bezuidenhoutseweg, Schenkwetering and the 1st v.d. Boschstraat (where today’s Utrechtsebaan is located). Van Liefland made urban expansion plans for Bezuidenhout in 1889, 1893 and 1896 (source: NAI: Van Liefland). The client for this was the Haagse Bouwgrondmaatschappij of Simons and Van Liefland (Van Creveld, 1999). Lindo designed the expansion plan which was approved by the council on March 16, 1897. As a counselor from 1895, Simons came up with plans such as a Volksbad, Volkspaarbank, Volksbibliotheek, Bewaarschool and Volksapotheek for the bad neighborhoods of The Hague. The Maatschappij tot Nut van het Algemeen carried out these ambitions (Van Creveld 1999). On December 23, 1914, Simons became the first director and co-founder of the Gemeentelijke Credietbank (1914-1921) and director of the Vereniging van Nederlandse Gemeenten VNG. This bank focuses specifically on municipal finances and the financing of housing law homes. On 24 January 1922, the bank changed its name to: NV Bank voor Nederlandsche Gemeenten (BNG, 2009).

Dr.ir. Cornelis Lely (1854-1929) was Alderman for Public Works and Property and Visschershaven (1908-1913). He was Lindo’s direct boss. Lely was a civil engineer, minister, governor and politician. At the age of 36 he was already appointed Minister of Water Management, Trade and Industry in the Cabinet Van Tienhoven (1891-1894) and in 1891 designed the plan for the closure of the Zuiderzee. From 1894 to 1897 he was a member of the House of Representatives. Then ‘Minister of Water Management, Trade and Industry’ in the Pierson cabinet from 1897 to 1901. In 1898 he steered the law for the Noordoosterlocaalspoorweg-Maatschappij (Zwolle-Delftzijl) through parliament. In 1902 he briefly served as a counselor in The Hague. From 1902 to 1905 he was governor of Suriname where he made possible the private plan for the construction of the Lawa Railway. From 1905 to 1909 he was again a member of the House of Representatives. However, from 1908 he became alderman in The Hague until 1913. The period when Berlage’s expansion plan was manufactured. After his aldermanship in The Hague, he again became ‘Minister of Water Management’ in the Cabinet Cort van der Linden from 1913 to 1918. In 1913, the reclamation of the Zuiderzee was included in the government program. In the meantime, he was a member of the Provincial Council of South Holland from 1909 to 1910 and a member of the Senate from 1910 to 1913. From 1913 to 1918 he was again Minister of Water Management and then from 1918 to 1922 member of the House of Representatives. With administrators such as Lely and later Drees, the boundary between local government in The Hague and government policy became diffuse.

Ir. Jurriaan Jurriaan Kok (1861-1919) was a member of the municipal council (1908-1913) and Alderman for Public Works and Property (1913-1919). He was a structural engineer, architect, artist and politician. After studying architecture in Delft, he worked for the architectural firm of D.P. van Ameijden van Duym in The Hague. In that office he regularly designed ceramics for the NV Haagsche Plateelbakkerij Rozenburg. In 1893 he was appointed artistic advisor to the pottery and then became its director until his aldermanship in 1913. The company closed in 1916 (Brentjes, 2007). Jurriaan Kok made a number of technical inventions that made it possible to produce the thin-walled eggshell porcelain. Many tile panels on facades in The Hague and in porches of Art Nouveau buildings came from Rozenburg. Many Asian motifs were incorporated, just like in the images on the vases. Jurriaan Kok probably made many of the designs himself and was inspired by his good friend Jan Toorop. In 1899 he officially changed his family name to a double surname, from that moment on he was called Jurriaan Jurriaan Kok. He was involved in the Bouwgrond Maatschappij Zandoord which developed the Scheveningse Geuzenkwartier.

The Liberal Union aldermen and councilors such as Jurriaan Kok together with the SDAP councilors brought Berlage to The Hague to produce the first consistent expansion plan in 1908, based on the new Housing Act (1901/02). Simons and Lely were both aldermen (1908-13) when Berlage defended his expansion plan in 1908. This highlighted the two major problems that were an obstacle to the implementation of the housing law: land ownership and financing. Lely introduced the leasehold system and Simons made financial provisions for the houses.

The architects of The Hague and the feast of the fin de siècle

In addition to aldermen, urban planners and clients, architects also played an important role in the aestheticization and the change of the cityscape. Most of the architects working in The Hague came from outside The Hague and were broadly oriented towards the developments that were going on in Europe. These were architects who were initially trained in the Dutch neo-Renaissance and who embraced the Art Nouveau and Wiener Secession between 1885 and 1905, after which they effortlessly switched to the historicizing Um 1800 Bewegung between 1905 and 1914.

The most iconic architects were Willem Bernardus van Liefland (1857-1919), Herman Wesstra jr. (1843-1911), Lodewijk (Louis) Antonius Hermanus de Wolf (1871-1923), Johannes Petrus Josephus Lorrie (1861-1944), Nicolaas Molenaar (1850-1930), Johannes Mutters (1858-1930), Jan Willem Bosboom (1860-1928), Lodewijk Simons (1869-1936), Jan Olthuis (1851-1921), Zacharius Hoek (1863-1943) and Johan Wouters (1866-1932).

Most architects from The Hague were not trained in Delft but at the Hague Academy or in cities such as Antwerp (Mutters) or Vienna (De Wolf) to get acquainted with the fashionable urban architecture. The views and work of Van Liefland, De Wolf and Lorrie went far beyond the emphasis on aesthetics. Because of his organizational and constructive genius, Van Liefland was the most successful and influential architect. As a counselor between 1898 and 1911 he was intensively involved in the breakthroughs through the city and the remediation of the poor neighborhoods. Together with Lindo, he mainly wanted to preserve the closed character and the picturesqueness. The architect De Wolf was his artistically gifted friend and collaborator who spread the Viennese ideas and Lorrie was the best student architect of the Hague Academy (Verbrugge, 1981) who would become a contractor and carry out the most beautiful works of De Wolf and Mutters. All three were Roman Catholics, did not come from the Hague milieu and would use all styles interchangeably without remorse, such as: neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance, Art Nouveau, Wiener Secession and Um 1800 Bewegung. Only De Wolf was exclusively in Catholic circles and had mainly Catholic clients. Van Liefland (Transvaalkwartier, Bezuidenhout, Prinsenvinkenpark) and Mutters (Wassenaar, Rijswijk) would also deal with street plans (Blijstra, 1996) (Verbrugge, 1981) (Niemeijer & Scheffer, 1996).

There was no fixed movement, movement, organization, initiator or policy. These were often loose working relationships, inspirations, fashions and novelties from other European cities that gave shape and color to this architecture. Most architects mainly sensed the time and the new urban culture that trickled down from Paris, Vienna, London and Berlin to The Hague. Cities that people read about daily in the newspapers and where, among other things, Gram (1893, 1906) gave a colorful account of it. It was a new architecture that did not look back and rejected the history of styles as a source of inspiration. This architecture appeared simultaneously in all European cities and was an architecture that used the new materials and production techniques and reaped the benefits of industrialization (Schlögel, 2008).

Scheurleer and Goekoop, the need for quality

As previously argued, directors of important building land companies such as Scheurleer and Goekoop were not unsympathetic to the ideas of De Stuer and Lindo, although Lindo saw nothing in De Steur’s rigid views. They felt that the city with beautiful neighborhoods and buildings could forget the period of ‘factory-based production of houses’, as Scheurleer argued during the council debate in 1891. Both directors were passionate about the culture and history (Bank & Buuren, 2000). Especially after 1890, the better neighborhoods of The Hague were developed by the two gentlemen such as. Duinoord and the Statenkwartier, the Regentessekwartier etc. in negotiations with Lindo and his department. Both men did not come from the world of builders and craftsmen but had an extensive cultural network and knowledge.

The Hague land trader and building contractor dr.mr. Adriaan Eliza Herman Goekoop (1859-1914) obtained his PhD in Leiden in 1888 on the subject: The state as a landowner. He bought a large piece of dune land between Scheveningen and The Hague from the Royal family. In the letter of 1/15 May 1889 from Secretary-Treasurer of the Grand Duchess to Goekoop, he stated that: ‘H.R.H. also knows you as someone who likes to advocate and exercise both the general city interest and a well-understood charity.’ (Cheap, 1953: 16). As long as the Grand Duchess lived, there was no question of selling Sorghvliet. After she died in 1897, there were still 360 hectares left of the domain, including her beloved Sorghvliet, the part between the Beeklaan, Laan van Meerdervoort and the Verversingskanaal. He then bought the part where the Statenkwartier and the Geuzenkwartier would later be developed, and the Zorgvliet estate with the surroundings where the Zorgvliet residential park would be built (Goekoop, 1888) (Hille, 1915) (Bank & Buuren, 2000) (Stal & Mulder, 2002).

His father Cornelis already traded in land and real estate and had bought large pieces of land from the estate of William II, west of the city, at the land auction. He was involved in the development of the district around the Koningsplein and of the Regentessekwartier, part of which was already carried out in his time. In addition to the land trade and the lay out of neighborhoods, his son Adriaan Goekoop was of great importance for archaeological research in the Netherlands and abroad. He stimulated and subsidized research by the German archaeologist Dörpfeld on Ithaca and at the Forum Hadriani, but also did his own research in Greece and published about it. In The Hague he supported the historical research and was on the board of the historical societies Die Haghe and Arentsburgh. He also sponsored institutions such as the Gymnasium Haganum (near the districts of Scheurleer and Goekoop), other schools and hospitals. He also contributed generously to the Hague Academy of International Law.

His wife was the well-known feminist, writer and freule Cecilia Goekoop-de Jong van Beek en Donk who had gained name and fame with her book Hilda van Suylenburg, a book in which the life of society in The Hague and the position of women were described in detail (Bank & Buuren, 2000). Through his noble wife, Goekoop found a connection in the noble circles. Cecilia’s sister Wilhelmina Elisabeth was married to the well-known Catholic composer and publicist Alphons Diepenbrock, who drew his poems for his compositions from German and French Romanticism and was in the circle of the eighties. Cecilia was good friends with Countess Bertha von Suttner, the Austrian-born pacifist and writer who had urged the Tsar to hold the Peace Conference in The Hague. Goekoop sold the land for the construction of the Peace Palace for a friend’s price. Perhaps not coincidentally, this land was located on the spot where Lindo had drawn the center of The Hague in 1895 and where a station of the steam tram was located. Scheurleer lived opposite and colleague Goekoop lived a stone’s throw away in the Catshuis.

The Hague banker and entrepreneur Dr. Daniël François Scheurleer (1855-1927), who had learned banking in the cultural city of Dresden, bought the excavated Dekersduintjes for the development of Duinoord I and II. In addition to being a banker and entrepreneur, Scheurleer was an enthusiastic musicologist and music historian. For his work he received an honorary doctorate from Leiden University. Scheurleer built up an impressive collection of Western and non-Western musical instruments and sheet music from around 1100. He published about the songbook and musical life in the Netherlands. The Scheurleer collection is now spread over various museums and institutes. All the streets and the square in his Duinoord district were named after important Dutch composers of the past.

That Goekoop and Scheurleer were not insensitive to culture and history was also evident from the neighborhoods they developed with their building land companies, which had major consequences for the cityscape. Representative squares and important streets were preferably built in a rich Dutch neo-Renaissance architecture. The prize winner was the Sri Wedari building from 1892 on Sweelinckplein by the architect Klaas Molenaar.

The Concours van Gevelontwerpen (competition of façade design) in the Duinoord van Scheurleer was one of the many strategies to put this architecture in the foreground, they were all exemplary projects on important urban spaces. The most beautiful urban ensembles of the cityscape of the fin de siècle would appear in the districts of Scheurleer and Goekoop, such as Duinoord with Sweelinckplein, Statenkwartier with Statenplein and Statenlaan, Regentessekwartier with Regentesseplein and Regentesselaan. These showed the typical image of enclosed urban spaces and a varied architecture taking into account daylight (wide streets, front gardens) and sky (open corners, building blocks, wide streets). The important avenues and squares of The Hague were a reminder of one common past.

The new Municipal Works and the German-Austrian urban planning

The reorganized and modernized Department of Municipal Works

In 1890, the call for quality in the city led to the reorganization of the Department of Municipal Works, to a new and broader demarcation of its tasks and to the recruitment of a powerful Architect-Director with a demonstrable vision: Isaac Anne Lindo (1848-1941). He held this post in Arnhem and explained a number of neighborhoods there that evoked memories of the Van Stolkpark. Under Lindo, the service would grow into a tightly managed and professional organization. He was a moderate liberal and atheist and great nature lover. He was an internationally oriented military engineer with a broad view of the problem and worked for seven years as a lieutenant of the engineers in Japan on waterworks. Via San Fransisco and other American cities under construction, he travelled back to the Netherlands. He spoke and wrote English, German, Dutch and French. He belonged to the cultural circles of The Hague, the publisher Martinus Nijhoff was his uncle and the Delft inventor, manufacturer and producer of cement stone and concrete products P.M. Lindo of the ‘Dutch cement brick factory’ was another uncle of his (Maarschalkerweerd, 1998) (Neve, 2000). Lindo would remain director until his retirement in 1918, and the city and the service went through a stormy development.

In 1888, new instructions were issued to the Architect-Director of Municipal Works, which replaced the old municipal instructions of June 5, 1877. The architect-director was now directly accountable to the municipal executive, and the Commission of Assistance in the Management of Local Works and Properties, later called the Local Works and Property Commission. Article 15 of the instruction stated that the Architect-Director had to issue an annual report of the innovations, improvements and embellishments that had been carried out. The task of the service now became to supervise the construction of streets by private building land companies, the maintenance and adaptation of old streets and the construction of public works such as sewers, utilities, bridges, canals, ports (seaport and Laakhaven) and the new electrified tram network. In short, everything that had to do with traffic circulation and urban facilities. The new service was given considerably more powers, but presumably Lindo also took these powers to himself.

In the period that followed, negotiations between building land and construction companies and the municipality became central in order to arrive at balanced and coherent street plans. Districts and neighborhoods thus became an integral part of the networks of electricity, gas, sewers and water, through roads and tram lines. The balancing act between the Department of Municipal Works, building land company, council committee, and municipal executive was a process that took place in all projects during this period. Lindo made good use of the time pressure of the companies that had taken out expensive loans from banks and had to limit their interest loss. Lindo used the disapproval of street plans, the non-adoption of streets or the non-connection to utilities as a means of pressure to make the entrepreneurs more lenient when it comes to planning changes.

Before Lindo came to The Hague, he already had the same position and task in Arnhem (1886-90). One of Arnhem’s expansion plans was the Burgemeesterkwartier where the streets were all given a curved course and the buildings showed a wide variety of architecture. Lindo was succeeded there by his right-hand man Ir. Jan Willem Cornelis Tellegen (1859-1921), a civil engineer who in 1901 became director of Building and Housing Supervision in Amsterdam and mayor of Amsterdam from 1915 to 1921. Lindo corresponded a lot with van Tellegen about many matters, including family matters that showed that they knew each other well (Lindo, 1910-1919).

Shortly after Lindo’s appointment, ir. Halbertsma in 1891 published a fantasy plan for the future development of The Hague, a suggestive monumental urban plan inspired by the developments that had taken place in Paris with Haussmann (Halbertsma, 1891). Wide boulevards were drawn through the city center and opened up the city, traffic circulation and monuments were central. The old city fabric was virtually wiped out. Halbersma’s plans for the Bezuidenhout and the Rivierenbuurt also had a strong formal character (Blijstra, 1969). In the end, none of these ‘French’ ambitions would be implemented, although a few years later Lely, as alderman, made another attempt to turn the Spui into a boulevard. At Halbertsma, the boulevards mainly served to beautify and accentuate the monumental buildings, just like in Paris, but Lindo would take a different course. It was only with Berlage in 1908 during the tenure of alderman Lely that straight Halbersma-like breakthroughs were again drawn right through the historic city.

The German-Austrian urban planning debate and the Lindo position

We were only informed about Lindo’s aesthetics and views on urban planning traditions and by looking at and comparing the plans he and his department produced. In his publications and diaries, he makes no mention of this and confines himself to dry lists of results, although the diaries from the period 1890 to 1910 have been burned. But the expansion plan from 1895 by Lindo shows a beautiful interpretation for the Statenkwartier with avenues with a curved course. Discussions in the council and correspondence with the council also show Lindo’s course. Lindo spoke his languages and was evidently well aware of what was going on in urban planning in the German, French and English language areas.

The core of the problem of modern urbanism around 1890 according to a.o. Sitte (1889) and Berlage (1892) was the reversal of the relationship between buildings and open spaces, especially in urban planning in the metropolises as developed in Europe (London, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Petersburg) and in North America with their boulevards and monumental representative buildings that became isolated in the city (Schorske, 1989) (Castex, Depaule, & Panerai, 1980) (Olsen, 1986) (Hall, 1988, 1998) (Woud, 1991).

In his preface, Sitte stated that it therefore seemed advisable to him to make an attempt to examine a fair amount of beautiful old square designs for the causes of their effect, because those causes, if properly understood, could produce a set of rules. Its application should then make it possible to achieve similar excellent effects. According to Sitte, the connection between urban space and buildings manifested itself best in squares. The degree of seclusion depended on the dimensions of the square and the height of the square walls. With a width of 30 meters, a height between 15 and 30 meters fit best. According to Sitte, individual buildings were only allowed to dominate a square in exceptional cases, such as, for example, churches that were often the focus from the beginning of urban development. According to Sitte, monumental buildings should be part of the square wall and not stand solitary in the space.

In his view, contemporary modern squares were scale less plains on which buildings drowned in space. In the past, the open space, the squares and the streets formed one contiguous whole. This brought about a feeling of urbanity and security among the viewers of the city. Squares and streets had been around for centuries and the buildings changed every few years within that ancient framework of the streets and squares. That gave the historic city its picturesque image and continuity. Sitte believed that the behavior of man as a social and artistic being could be influenced by the cityscape. A city had to meet psychological needs and city plans had to create a cityscape by paying special attention to the relationships between streets, squares and buildings with the aim of creating a closed cityscape. Every city has a ‘character’, according to Sitte, and that must be recognized and used. Sitte’s theory was more than an aesthetic theory for urban interpretation. Aspects such as terrain knowledge, morphology and history of the landscape, analysis of population development, the economy and traffic had to be included.

Lindo’s director of Building and Housing Supervision, A.J.M. Stoffels, argued in a joint publication of directors and officials Van Gelder, Jurriaan Kok, Lely, Lindo, Stoffels and Van Zuylen van Nyvelt from 1913 that the service could not only do it with traffic circulation (Gelder H. , et al., 1913). They deliberately wanted to break the rigid grid with the long sight lines and they wanted to influence the image by having the roads intersect at different angles:

‘These circumstances have had a major influence on the architectural development of the buildings. It stimulated study and thus gave rise to great diversity and improvement compared with the phenomenon that also occurs in The Hague, that numerous houses of the same type were built in uniformity, in long rows.’ (152, 153).

In the background, there was a debate between German and Austrian urban planners about the ‘fait primitive’ of urban planning: the ratio or the experience. A camp that considered ’the experience of urban spaces’ especially important and a camp that mainly advocated ’the rational organization’ of urban spaces. The debate was about the starting points for the lay out of streets, should structure (traffic circulation) or experience of the city dwellers be used as a starting point? Following the example of German urban planners, they limited themselves to the main structure, a variant of the grid, and left the interpretation to private individuals.

Sitte (1889) quoted a report from the Deutsche Bauzeitung of 1874:

The design of urban sprawl essentially consists of identifying the main characteristics of all means of transport – streets, horse trams, steam trams, canals – which must be dealt with systematically and therefore extensively.

The street pattern should first include only the main routes, taking into account as much as possible existing roads, as well as those secondary routes that are prescribed because they are determined by local conditions. Lower-scale classification should first be addressed according to future needs or left to the private sector.

Grouping different districts boils down to choosing a suitable location and other characteristic features, and is only a matter of sanitary regulations that apply to businesses if there is no other option. (Sitte, 1889: 128)

Sitte did not agree with this minimalist urban planning practice. He mainly responded to Stübben’s urban planning principles. He was the quote from his standard work Der Städtebau (1890): ‘überall Schema, keine Eigenart’. Stübben brought the work of another founder of urban planning Richard Baumeister to a climax: the classification of the city as a grid, triangular or radial scheme. Baumeister described this in his book: Stadt-Erweiterungen in technischer, baupolizeilicher und wirtschaftlicher Beziehung (1876).

The great champion of the first camp was the Viennese urban planner Sitte and of the second camp his fellow townsman Otto Wagner (1841-1918) and the great Berlin urban planner Hermann-Joseph Stübben (1845-1936). The American cultural historian Schorske (1989) contrasted these two traditions of urban planning and presented them as irreconcilable contradictions. By juxtaposing Sitte and Wagner, Schorske also established himself in a long tradition that began with Brinckmann and that saw urban planning primarily as a road grid with objects (Woud, 1991). According to Schorske, Sitte focused on the past and tradition and fell into historical musings and thus wanted to correct the city’s lack. Wagner focused on the future and saw the usefulness as a principle for the city and the buildings and thus wanted to save the impoverished population. However, there was more going on. Sitte did not believe in evolution as it was assumed in the history of styles.

The art historian Reiterer (2003) showed a different picture in her study than Schorske. In fact, Sitte did not meet the criteria of modernism with its emancipatory goals and belief in progress. It was mainly Sitte’s implicit rejection of the ‘mechanical’ history of style with the presupposed improvement in the distant future. Sitte did not use an ‘overall theory’, just as Darwin never used the term ‘evolution’ to explain his ideas. On the visual aspect, Sitte noted that: ‘From an artistic point of view, only what can be overseen, so one street, one square at a time, is important’. Furthermore, the hygienist position is also ignored. Sitte was trained as a physician. Although new cities were given wide boulevards, a network of small inner towns was created in the building blocks where fresh air and sun were lacking. The relationship between buildings and open space was therefore rightly mattified. Both Lindo in Duinoord and later Berlage would elaborate on this theme.

Sitte was not opposed to modern urban planning, in his opinion many problems were solved by regulating the street pattern but at the same time also created. He argued: ‘Modern systems, yes! Strict systematic approach to everything and not a hair from the once imposed template, until the genius has been tortured to death and all the lively feeling has been stitched into systematics – that is the hallmark of our time.’ (Sitte, 1889: 99). Sitte proposed a reconciliation between how one experiences the city, the beautiful squares and main streets, and the practical aspects of the city. In Sitte’s vision, the artist first had to design the system of beautiful main streets and squares, and only then did the mass of residential areas that was abandoned to the free market follow (Sitte 1889: 100, 141).

According to Sitte, in old cities there was originally only the continuous street facades, the closed urban space. According to him, modern urban planning aimed for the opposite, for the loosening, the creation of separate blocks: housing block, square block, garden block and the solitary monumental building in an empty space on the site of such a block. In short, filling in a road grid. According to Sitte, there was a wrong tendency in that system. We would mathematically define the ideal that such designs pursued as striving for a maximum amount of building lines along the street, while the visual aspect and spatial perception should be central to urban planning, just as with the Baroque.

For Lindo, the ‘fait primitive’ lay in experience, although he depended on building-land-companies. His strategy was for his department to outline the expansion plans with main streets and thoroughfares, and to produce the various interpretations of these together with the various building land companies. The service also dealt with the residential streets. Before 1890, residential streets were a matter for building land companies, which had to meet a number of previously described basic requirements. At that time, through and main streets were both a matter and a problem for the municipality. Lindo would pay a lot of attention to the system of main streets. Lindo had devised a profile for each type of street for the articulation in the urban space. In a publication of the municipality of The Hague by Van Gelder, Jurriaan Kok, Lely, Lindo, Stoffels and Van Zuylen van Nyevelt from 1913, the approach was clarified (Gelder H. , et al., 1913). The city access roads (>30m) and the main streets (22-27m) taking into account traffic circulation and tramway routes, and the residential streets (>10m). Because of the front gardens that Lindo added, residential streets usually became wider. Facilities such as schools and churches were usually not included in the street plans, but in the plan for Transvaalkwartier, Van Liefland already reserved space for three schools in advance, a novelty.

The village character and the green avenues

The old cityscape of the neutral village in the leafy greenery was not forgotten either. That theme would even be deliberately used by the nature lover Lindo. The village character of The Hague was enhanced by the road profiles of main streets and access roads, with the leafy greenery and front gardens in particular determining the image. The system of main streets consisted partly of the existing old streets parallel to the beach walls that were extended. In between came a system of main streets: perpendicular (as a separation between different districts) and diagonally with kinks (as access to the neighborhoods). All these main streets were designed with a corresponding street profile. In the street plans between these main streets, the direction and width of the street, the height of the facades, the chamfering of corners and the construction of utilities such as sewers were laid down in council decisions, by deeds of transfer of the land and in the building regulations (Gemeente ‘s-Gravenhage, 1948)

The building-land-companies paid for the construction of the streets and the associated costs such as raising, paving, sewerage, drainage and street lighting. The land for the public roads was then transferred to the municipality free of charge. Sometimes this also happened when entrepreneurs themselves did not have a direct interest in it, as Goekoop did with the widened part of the Laan van Meerdervoort between the Verversingskanaal and the Beeklaan around 1893 (Acts of the city council 1893, annex 226: 54-55).

These distinguished streets with the most beautiful houses were specifically designed with a central zone for pedestrians with shells and a double row of lime trees (Gelder H. , et al., 1913). That was also the design that was used for the muffled canals within the canals. During the interwar period, the municipality cleared most of the rows of trees and disappeared shell paths for the benefit of increasing car traffic.

There were no shops or facilities along these main streets and access roads. At Duinoord, shops would not be allowed along the main streets and at other through streets from this period there are none. Whether that was determined by Lindo or by the building-land-company that wanted to raise the status of the district remains unclear. Shopping streets often arose in a natural way such as Reinkenstraat (Duinoord), Frederik Hendriklaan (Statenkwartier) and Weimarstraat (Regentessekwartier and Valkenboskwartier). In this way, the focus of all activities was placed within the districts and not along the representative and functional main streets. At intersections or traffic squares of main streets there were also no height accents or monumental buildings. The main streets between the neighborhoods were usually straight, but the main streets in the neighborhoods were diagonally in the orthogonal structure and were given kinks so that the neighborhoods had a private character. Nowhere are there long sight lines from inside the neighborhoods or the horizon can be seen. The main streets formed a spacious ring road around the old town that was thus spared from through traffic.

Wide, beautiful access roads to the city were also considered of the utmost importance as entrances to the residence. The discussion around the construction of the Laan van Nieuw Oost-Indië (NOI) in 1898 shows this. In 1893, the ‘Haagsche Maatschappij van onroerende goederen’ asked permission for the construction of part of the Laan van NOI (Acts of the Council 1893, Annex 227: 55). In April 1898, a conflict arose between the society and the city council over the width of the street (Acts of the Council 1898, Annex 246: 76-78). The company came up with a width of 14 meters, the municipality thought that was too small for a main access road and not only for traffic reasons: ‘… not to mention that the wealth requires larger dimensions for that part.’

A stalemate ensued. In the background there was also another conflict between the society and the municipality over a street plan of the society in the Schilderswijk near the Jan van Gojen and Van Ostadestraat. Part of the Laan van NOI was 30 meters wide. In a compromise, the construction company proposed to make the remaining part of the avenue 23.5 meters: two lanes of 6 meters with a center strip of 7.5 meters and along the houses on both sides 2 meters of sidewalk. The front gardens of the houses then became 3.25 deep so that a total of the requested 30 meters would be present between the facades. The rows of trees, which were apparently already present, could then be maintained. The municipality thus made a compromise in favor of a beautiful access road and to the detriment of a workers’ quarter such as the Schilderswijk.

Residential streets with light, air and intimacy

Lindo’s plans also included front gardens for more air and light. At the beginning and end of the residential streets there were no gardens so that there was a narrowing, in the other part there was a widening with front gardens. Residential streets not only got more daylight and air, but also intimacy and seclusion. From 1892 onwards, the building code set the standard that the houses to be built could not have facades that were higher than the street width from the pavement surface (Gemeente ‘s-Gravenhage, 1948). Before 1892, facades were not allowed to exceed 1.5 x the width of the street, although the council decisions after 1876 almost always included the condition 1:1, as described in the chapter above. It was counted as the cornice or half height of the top façade. For residential streets, 12 meters between the facades was common, but the nature lover Lindo introduced front gardens and therefore the streets had to be 16 meters wide. The argument he made was that the air circulation in the streets improved so much. The roadway was 5 meters wide with 2 meters of sidewalk on both sides and then 3.5 meters of front yards on both sides.

This was a good thing for the municipality, because now it was no longer necessary to build and maintain 12 meters of street but only 9 meters of public pavement. The councilors, who had no interest in the building land company in the Transvaalkwartier, had ears after this (Acts of the Council 1898, Annex 157, 15 March: 46-48 & Acts of the Council 1898, Annex 213, 13 April: 67-68). The old rule regarding the rounding of corners with a radius of 3 meters was also changed in the period of Lindo. At the Regentessekwartier no chamfering of corners was yet required, but in later plans such as Transvaalkwartier these were prescribed. If no corners were indicated on the drawings for the buildings, it had to be chamfered equilaterally with at least 2.75m1 on the building lines, or rounded with a radius of 2 meters at angles smaller than 60 degrees (Gemeente ‘s-Gravenhage, 1948) (Acts of the Council 1893, Appendix 137, March 20: 33-34; Acts of the Council 1893, Appendix199, April 17: 47-48; Acts of the Council 1894, Annex 9, 5/8 January: 2-4).

The village character was emphasized with the front gardens at the neighborhoods for the middle class in residential streets such as the 2e Schuytstraat, Nicolaistraat, Danckertstraat (Duinoord), Vivienstraat, Ten Hovestraat, Van Hoornbeekstraat, Frankenslag, Adriaan Pauwstraat, Antonie Duyckstraat, Van Beverningkstraat etc. (Statenkwartier), Willem de Zwijgerlaan (Geuzen- and Statenkwartier), Copernicusstraat, Galileïstraat, Fultonstraat, Stephensonstraat, Thomas Schwenckestraat, Hendrik van Deventerstraat (Regentessekwartier and Valkenboskwartier). The feeling of commonality that played a role in the Hofjes van Van Liefland was thus also given shape in Lindo’s urban planning with the residential streets.

This theme would be further developed and perfected during the interwar period. In the council decisions, these standards were explicitly laid down as a condition for granting permits to the building land company. The building land companies stimulated the quality of the buildings by organizing façade competitions, such as at Duinoord and Bezuidenhout. As previously argued, building land companies sometimes also included provisions in the land contracts with construction companies to prevent the level in the district from going in the wrong direction and to guarantee the sale value of the land. Sometimes the selling party made demands, as the Grand Duchess did with Duinoord. The municipality also tried to include provisions on quality in land contracts about the lay out and appearance of the district and its buildings, according to Stoffels (Gelder H. , et al., 1913).

Individualization of the house

For the cityscape of the fin de siècle, the far-reaching individualization of the typology of the distinguished house is characteristic. This manifested itself in the articulation of the building mass, the arrangement of the interior spaces, the new relationship between public and private, materials and colors. Ultimately, this individualization would lead to the Housing Act of 1901 in which the government contributed to the objective of a private rental home for each family. According to Bakker Schut (1939) and the municipality of The Hague (1948), there are three periods in housing construction in The Hague that are clearly visible in the typology of the houses: (a) before 1892 with its serial housing (laissez-faire); (b) the period of individualization between 1892 and 1916 (fin de siècle); (c) the period of collectivization of housing from 1916 to 1933 (interwar period) (Bakker Schut, 1939) (Gemeente ‘s-Gravenhage, 1948).

Lindo’s enclosed urban spaces are inextricably linked to the typical housing of the fin de siècle. From 1892, houses could only be built on the street because the Stedelijk Keur from 1841 was finally withdrawn. No slums anymore in the courtyards. For years, the hygienists had fought against the abuses in the courtyards. This meant that from now on every house had to have a front door on the street, and that led to a stormy development in housing types. Initially only the ‘upstairs and lower house with back house’ where the stairs could be both inside and outside. During the interwar period, the Hague the residential-apartment-building appeared with four and sometimes six apartments and two ground floor apartments. However, as photographs shows, there were already early examples of this new type apartment buildings. From a typological point of view, according to Bakker Schut (1939), the upstairs-downstairs-apartment-houses or upper-lower-apartment-houses gradually developed into this larger residential-apartment-buildings of the interwar period.

In both cases, the buildings remained predominantly in three stories. The upper-lower-apartment-houses were often given a flat roof with a façade protruding above the roof, with the upper roof masonry being terminated by battlements or elevations at the building walls. The architecture often referred to the fashion of the time, Art Nouveau and Wiener Secession. The ground floor apartment had one storey and usually a rear extension with two or more floors. If there were two or more upstairs apartments, there was a stone external staircase that was within the building volume. In Amsterdam and Rotterdam staircases were usually closed, in The Hague it was forbidden due to fire regulations and the new regulation of 1892. Each house had its own toilet, a separate kitchen and two sometimes three bedrooms. Later during the interwar period, a washroom was added. In the beginning, these houses were built next to each other by construction companies, such as in Duinoord, Transvaalkwartier and the western part of the Schilderswijk, the Regentessekwartier and the Valkenboskwartier. On the representative squares and streets came the more expensive houses and the builders emphasized the individuality of the houses, even if they were built in a row next to each other by one architect or construction company. All kinds of turrets appeared above entrances on the roofs.

After the First World War, the lay out of the houses changed. The individual character of the houses disappeared and individual houses merged into the whole of the urban block. The urban blocks were divided into residential-apartment-buildings units of six to eight apartments. Two downstairs apartments that had a front door right on the street. With an indoor open external staircase, one came to the first floor with the front doors of the other apartments. In 1920 further provisions were enacted to prevent rear building and in 1931 the Housing Act was revised and building lines on all sides were established. The residential buildings were given a depth of ten meters to ensure daylight and ventilation air inside. In addition to the typological innovation, there was a renewal of the use of materials.

Revolution in the development of techniques and building materials

The possibilities for individualization and aestheticization were given a strong boost by the revolution in techniques and building materials. Until 1890, burned and sanded clay bricks (in red, yellow and pink tones) with white bands, keystones and lots of white plaster dominated the cityscape. After that, the new materials quickly found their way into architecture and the appearance of facades changed drastically, although the old materials were still widely used. New were the applications of bright red extruded bricks (hard, smooth, sharp edges and with perforations), sand-lime bricks in various shades and lush shapes, glazed stones in white, yellow, blue, red and brown, natural stone, ceramics, reinforced concrete, cast iron and large glass surfaces (Gans, 1960, 1966) (Blijstra, 1967, 1975) (Verbrugge, 1981) (Lintsen et al., 1992-1994) (Lintsen, 2005) (Stenvert & Tussenbroek, 2007).

The Hague variant of this architecture had bright colors and strongly articulated building masses. Exotic motifs were often included in the architecture, especially from the East Indies (Verbrugge, 1981). Combination of brick and sand-lime stone was also common. Cast iron bridges, columns, lampposts for the gas lighting and fencing appeared all over the city. But especially the cast and drawn glass for the shop windows with cast iron support. Many storefronts in The Hague showed sumptuously curved and carved frames of tropical hardwood, tile panels and ceramics in all kinds of shapes and especially with the typical green-blue color. With this wide variety of materials, emphasizing the individuality of the client became much easier for the ambitious architect.

In the seaside resort there was plenty of experimentation with reinforced concrete, cast iron and all other new materials. At Het Wandelhoofd (the Old Pier) by the architect Van Liefland, a complex supporting structure of cast iron and concrete was built and calculated by the Belgian constructor Emile Wyhofski in the period 1900-1901. Van Liefland’s Palace Hotel from 1903-1904 was probably the first building with a full concrete skeleton in The Hague and with a parking garage under the building in the Netherlands. Circus Schumann or Circus Cascade or the current Circus theater of the architects Van Liefland and De Wolf was given an impressive roof in 1903 from a shell of concrete with iron to absorb the tensile stresses.

The rising prices for bricks, which required expensive fuel, and the rising wages for masons were the reasons for the municipality to investigate reinforced concrete as a building material for housing construction. Bakker Schut (1939) described an experiment with 8 double houses, each according to its own method and construction method. Presumably these are the concrete houses on the Westduinweg and the Tarbotstraat. After the trial, the municipality decided a few years later in 1921 to build 42 houses in granulated concrete. When tendering for homes in Duindorp, the contractors were also allowed to pay a price for the execution in slag concrete, but the price for brick and labor had now fallen so that they opted for a traditional construction, according to Bakker Schut. In the case of granulated concrete, rubble granules were processed into concrete with cement, in the case of slag concrete, blast furnace embers were used as aggregates.

The retail warehouses of the fin de siècle

Nowhere was the need to distinguish oneself as great as in stores. As argued, between 1870 and 1910, the city center of The Hague gradually changed from a packed residential city to a chic service city with retail warehouses and offices with its own image. Store warehouses were given spectacular open facades with huge glass surfaces with a cast iron support. The shopping street ran spatially deep into the brightly lit shop windows. In the experience of shoppers, interior and exterior merged into a whole.

At the Haagse Passage from 1885, the windows and shop windows were still of modest dimensions. Especially between 1898 and 1908 there was an acceleration in which many innovations were introduced. The first example built was the Toonzaal Van IJzergieterij Beekman from 1898 by the architect Bosboom at Denneweg 56. This showroom was followed by the Toonzaal Voor Een Fietsenhandelaar from 1902 by the architect Hoek at Noordeinde 12-14. And Winkelmagazijn De Duif from 1905 by the architect Molenbroek at Venestraat 17.

After these modest experiments with cast iron and glass, three shop warehouses followed with huge cast iron constructions with large glass fronts and imposing glass roofs and voids so that the merchandise could be viewed in daylight. Fashion warehouse Schröder from 1906 by the architect De Wolf and contractor architect Lorrie at Groenmarkt 25 and 26. This warehouse was very similar to the Herzmansky Company’s shop warehouse, Mariahilfer Straße from 1897-1898 on the Maximilian Katscher in Vienna. The interior recalled the works of Hofmann and Mackintosh from the same period and must have been very impressive (Verbrugge 1981: 99). The architect De Wolf studied in Vienna and sat in the lecture hall with Mackintosh listening to the lectures of Otto Wagner (Verbrugge, 1981). Grand Bazar de la Paix from 1906 by the architect Dorser at Spuistraat 45-47. This was the first real bazar of The Hague, where all kinds of specialisms were united in one building, just like in the first bazar in Paris. In 1907 another part was built and the area was doubled to 5200 m2. After the breakthrough at the Grote Marktstraat, the bazar was extended to the new shopping street of the city. Hollandia warehouse from 1908 by the architect Meyneken at Prinsegracht 42. Café Hollandaise from 1906 by architect De Wolf at Groenmarkt 29 had a beautiful billiard room with a side-curved light cover, like at the Postsparkasse in Vienna. Unfortunately, this was demolished.

All large warehouses were inspired by the Vienna Secession. However, in the situation in The Hague, the façade was much more open than in Vienna. Typologically, this building consisted of a cast iron construction, imposing glass roof (if possible) and on the floor’s galleries around a large open void with open facades on the street with large glass fronts so that the merchandise could be viewed in daylight.

The Pander warehouse, on the Weversplaats, on the corner of Vlamingstraat and Wagenstraat, also had one of the most impressive shop windows with huge glass surfaces for that time. According to Gram (1906: 86), there was a struggle going on between entrepreneurs. The competitor Peek & Kloppenburg had considerably widened the façade of her opposite building and adapted it to the new era. Pander had to go along and annexed one building after another to merge into a new store. Gram even suggested renaming the Vlamingstraat Panderstraat. At the new Pander warehouse, Gram also noticed an architectural change of significance: ‘Because of its austere simplicity and awe-inspiring dimensions, this façade with its huge mirrored windows makes a bigger impression than could have been achieved with all kinds of decorations and variety of colors.’ (Gram 1906: 88). The Pander warehouse with its huge glass surfaces and sandstone wall dams was an abstract building, almost completely devoid of unnecessary details or historical references. The transparency between the street and the shop window was maximum and they seemed to merge into each other. Gram argued about the transformations that:

‘But by the way, as far as the decoration and the façade of the warehouses are concerned, a man from The Hague, who had not seen his beloved Hoog-, Spui- or Veenestraat in 25 years, would join forces in amazement if he suddenly found that sought-after stroll site again. Back then, there was a single warehouse here and there, which made large toilets or was allowed to rejoice in an ornate façade – now these busy streets literally offer an incomparable sample of all kinds of tasteful storefronts, in all kinds of styles and fantasies, of coquette displays behind high mirrored windows, in short, of the most remarkable attempts to attract the attention of the public.’ (Gram 1906: 84).

The first Art Nouveau building from 1895 in The Hague was designed by Mutters, with the Bakery and Tearoom Firma Lensvelt Nicola from 1895 at Venestraat 29, a very rich and exuberantly decorated building, characteristic of all Mutters’ work. This was immediately followed by Lorrie’s House from 1896 at Smidswater 26. The architect contractor Lorrie executed the left part, his own house in neo-Gothic style and the right part in Art Nouveau. The left part was meant to convince the conservative customers of his craftsmanship, the right part was meant to get the visionary customers on board, and that half would get Lorrie.

From 1905 to 1914 a counter-movement started in which natural stone and historical references again played an important role: the Um 1800 Bewegung. It was an urban architecture inspired by examples from American cities such as New York, Chicago and San Francisco. Especially at the breakthrough at the Hofweg and the Buitenhof, buildings appeared in the style of the Um 1800 Bewegung. This architectural style with a lot natural stone was not so much applied to retail warehouses or government buildings but rather to offices, banks and insurance (Regt, 1986) (Rosenberg, Vaillant, & Valentijn, 1988).