Cityscape of international significance and allure 1935-1965

‘ … that it used to be and that, we hope, it will soon become again: the city of international significance and allure.’ (Mayor De Monchy, Acts of the City Council of 3 December 1945: 12)

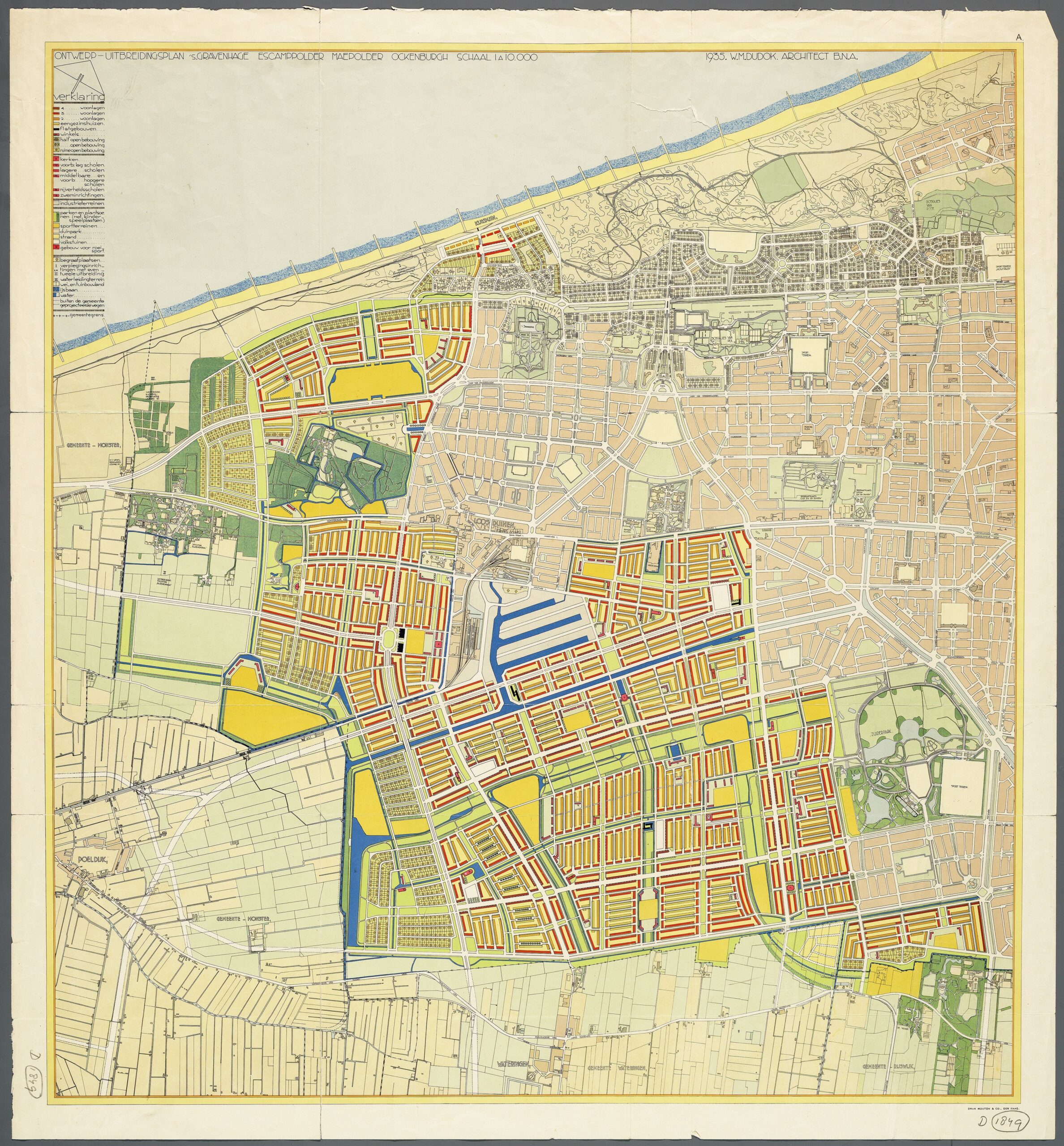

The green village character of The Hague 1933

The rediscovery of local character

On July 10, 1933, following a proposal from the college, the council decided that the draft expansion plan for the southwestern part of the city should be handed over to a competent urban planner. However, the very elderly Berlage renounced his advisory role. The Association of Dutch Architects (BNA) put forward the Hilversum architect Willem Marinus Dudok (1884-1974) as the new city architect for The Hague. A year later, in 1934, The Hague also got a new mayor; the conservative liberal Salomon Jean René de Monchy (1880-1961). Van Gelder, a friend of Berlage and party ideologist of the SDAP, rhetorically addressed the question of ‘individual character’ (Van Gelder & Deventer, ed. 1934). Wils, who took on the architectural part of Van Gelder’s books, argued about the character of The Hague:

‘The Hague was and still is partly a great garden city.’ … ‘The Hague can still be called ’the Green City of the West’. In many streets and even in entire neighborhoods, the trees and greenery dominate the cityscape and give it a soothing rest.’ (Van Gelder & Deventer, eds. 1934: 53). In addition to its green character, Van Gelder also described another quality: ‘There is a second characteristic, which determines the typical city character of The Hague. It’s the predominantly low buildings.’ (Van Gelder & Deventer, eds. 1934: 54). In 1934, Wils advised on future developments: ‘It was undoubtedly an obvious and attractive idea to implement the method of low buildings in the expansion, with the beautiful cityscapes of the city center in mind and based on the tradition that gave The Hague the nickname of ’the largest village in Europe’. Park-like wide roads and, above all, that abundant stock of tall trees and beautiful dune parks almost attracted and forced low houses. Nature had to be the dominant element in the new city.’ (Van Gelder & Deventer, eds. 1934: 56).

According to Wils: ‘Characteristic of The Hague are the many villa parks and garden city districts’ (Van Gelder & Deventer eds. 1934: 58). Especially Marlot of the architect Brandes and the garden city Houtrust (now Vogelwijk) of the architect Verschoor were seen as examples for the new development, but the highlight for Wils was the villa park Zorgvliet that the German urban planner Henrici had worked on. Despite the idea that De Monchy, Vrijenhoek, Wils, and Dudok had about the green village character, The Hague was in a deep hibernation and hardly any construction was taking place.

The choice of Dudok as city architect was a deliberate decision that was influenced by his views on urban development. The architect-alderman of the SDAP, Vrijenhoek, highlighted the contrasting characteristics with Amsterdam. However, Dudok’s position also played a crucial role. It seems that Berlage’s advisory role was no longer desired.

‘The Hague doesn’t have a metropolitan allure. Monumentality will not be achieved at all, or only sparingly: ‘The Amsterdam School’, closely related to the leadership of the BNA, is not the compass on which to set course here. The Hague has its own personal character, and when Dudok is seen as the man who will turn that around, I must warn: that will end in failure! It is in that light that my recommendation of Dudok by the BNA must be viewed. And then the great question remains, which still needs to be answered: Can anyone arrange for the future expansion of the city, which is a continuation of the historical development of our city? … Berlage’s position was a completely different one! That was the position of a consultant, and here we are explicitly dealing with the position of a designer. … It was also clearly stated in the Build-up Report: we have to get rid of the advisory role. We need to have a responsible designer.’ (Vrijenhoek quoted by: Freijser & Teunissen 2008: 76)

With the construction report, Vrijenhoek refers to ‘The Development and Construction of The Hague (1931-33). Relations between the old master builder Berlage, Dudok, and his friends Wils and Oud were good. Wils worked at Berlage’s office, while Oud and Dudok carried out various projects together. Dudok even intended to establish an agency with Wils after World War I. At Berlage’s urging, Oud spent several months studying under Theodor Fischer in Munich, one of Germany’s most experienced urban planners. Fischer emphasized the importance of achieving an aesthetically pleasing cityscape, with one of his principles being ‘die Steigerung des Charakterischen,’ which focused on highlighting the unique elements of a city or district. This principle would also become one of Dudok’s guiding principles, as he always aimed to design with the character of the specific city in mind (Van Bergeijk 1995:17).

The influence of the Hamburg architect Fritz Schumacher on Dudok’s thinking was also considerable. It concerned the positive effect of schools on the ‘Charakter der anonymen großstädtischen Massenbauten’. Following Schumacher’s example, Dudok wanted his schools to spread culture among the broad masses of the population (Van Bergeijk 1995: 28). As the great museum reformer, Van Gelder had been committed to the elevation ideal of the SDAP for years. In his view, the museum had to be brought out of isolation and made accessible to everyone. This was similar to the ideas about ‘Neighborhood Units’ of the conservative Clarence Perry (1929, 1939) a few years earlier in America. Schools and churches were the beating heart of every neighborhood. Dudok was seen as a supporter of the new housing culture as propagated in Germany and Anglo-Saxon countries, in which a strong anti-urban attitude can also be found (Van Bergeijk, 1995: 102).

Analogous to the human body, for Dudok, the city is an organic whole in which there is a logical connection between the parts. This whole must be developed harmoniously and in a controllable manner. Bad spots should be removed and filled in with healthy ones. Above all, care must be taken to ensure that the city does not grow wildly and destroy the surrounding landscape. This is the task of the urban planner, who must first and foremost act as a technician but also ensure that his expansion plans create the possibility of a beautifull city.

Dudok wanted to strengthen the open green village character, not sharply demarcate the city and reinforce the long lines with through roads extending beyond the city. He wanted to maintain and enhance the typical green character of The Hague. Berlage, too, had this intention with his plan from 1908. The starting point to achieve this beauty is the individual character of each city, which can be discovered through an analysis of its historical growth.’ (Van Bergeijk, 1995: 68). This shows the influence of Patrick Geddes (1915), the founder of the ‘regional survey’ and of Fischer. The essence was that the urban planner should first understand the spirit of the city, its historical essence. According to Van Bergeijk (1995: 81), this was the local character that Dudok spoke of in his explanations.

Dudok further developed the characteristics of The Hague from the seventeenth century, particularly emphasizing the open connection of the city with the surrounding land to create a green continuum. This, combined with the low-rise buildings, helped to create a typical village appearance. During the Golden Age, The Hague had always been an open village with stone roads leading to pleasure gardens in the area. The city did not have sharp boundaries of fortifications or city walls. The transition was made smoother by the wide green strips between the neighborhoods and by reinforcing the natural orthogonal structure.

Furthermore, Dudok adopted the urban planning method of Lindo and Berlage: neighborhoods and districts were laid out in a web of motorways (parkways) and tram rails. Residential areas were turned inwards with their own enclosed squares (like the neighborhood unit of Perry). Like Berlage, Dudok wanted to open up the old city further by means of breakthroughs. Dudok opposed stylistic architecture and the copying of historical styles and orders and defended modernism with its objectivity and functionalist principles and its crystalline space art, in which a composition of masses, planes, and spaces in between gave beauty to the buildings, the interiors, and the urban space. Although it had to take utilitarian requirements as its starting point, it had to rise above the question of utility and make possible a ‘characterization of the ideal meaning of the building’. (Van Bergeijk, 1995: 16).

In Dudok’s eyes, the characteristic feature was the connection with history. The traditionalism in Dudok’s work was not concerned with imitating historical styles but stemmed from the view that architecture is a spatial art that embodies traditional and universal values. Architecture had to possess eternal value and be able to express an idealistic meaning (Van Bergeijk, 1995: 121). Dudok was considered the right man in the right place in The Hague; everyone believed that only he could enhance the village and green character of The Hague.

Expansion plan Escamppolder Maepolder Ockenburg 1935

In the 1935 Draft Expansion Plan for The Hague’s Escamppolder, Maepolder, and Ockenburg (the expansion plan for The Hague Southwest), the idea of perimeter urban blocks and monumentality was abandoned, and the concept of a green continuum was emphasized (HGA z.gr.1849). In a memorandum from 1936, Dudok further explained the plans (Dudok W. , Nota van Toelichting op het Ontwerp-Uitbreidingsplan voor het Zuid-Westelijk gedeelte der Gemeente ’s-Gravenhage [Escamppolder, Maepolder en Ockenburg], 1936), stating that:

‘The Hague is first and foremost a residential city: a city that owes its origin and development mainly to its beautiful location. Forest, sea and dunes, and inland: in the Middle Ages, a beautiful Dutch landscape made the counts of the country choose this place as their place of residence. This regal example has been followed by many thousands over the centuries. … In the further development of the city, every effort will have to be made to highlight the advantages of its location, or at least to preserve them.’ (Dudok, 1936: 3)

For Dudok, the forest and dune landscape were preeminently the areas for relaxation, recovery, and upliftment of the urban population. According to Dudok, the expansion of the city does not require the loss of natural beauty. He believed that the main characteristics of The Hague are the grid street pattern that follows the geomorphology of the landscape. This grid pattern is the most obvious choice for a motorway network. The residential, recreational, and working areas are separated by residential streets within the pattern of the traffic routes. The facilities such as sports and relaxation areas, as well as greenery, are located in the residential areas. The open urban blocks are relatively long, spanning more than 300 meters, in order to save on expensive road surfaces. The design of the building profile and block direction ensures optimal fresh air and sunlight in the houses. Dudok proposed four floors along main traffic roads, three floors along green lanes, and two floors in residential streets. High-rise buildings of 10 to 15 storeys were also planned for suitable points in the district. For Dudok, the urban block is the scale of architectural unity.

In his explanation, Dudok specifically mentioned the book De Hedendaagse Stedebouw (1912) by the mayor of Utrecht, Dr. Fockema Andreae, with his reflection on the beauty of cities and their monuments from the past. In his explanation of the green continuum, Dudok argued that: ‘I have thought that I would achieve the greatest effect and the greatest possible freedom to adapt to changing needs by uniting the useful and beautiful greenery in one system. This system should organically permeate the plan, reaching the residents everywhere and vice versa, drawing them from all points.’

In these post-war lectures, Dudok emphasized the importance of incorporating green recreation areas into urban planning. He referred to the systematic veining of the stone city with green spaces as a modern element of contemporary urban planning. Dudok believed that the need for sunshine, greenery, and relaxation near urban homes is an essential aspect of modern living (Dudok, 1950, 1951) (Leeuw-Roord, Rijven, & Smit, 1981). On his seventieth birthday, Dudok reiterated this message, stating that the systematic use of recreational strips that penetrate the city like veins is also a characteristic feature of modern urban planning. Regarding the expansion plan for Southwest, construction had been delayed for several years due to the crisis in Europe. Finally, in 1949, sub-plans such as the second part of Moerwijk (West, East, and South) and Morgenstond were implemented. The first part of the Moerwijk Expansion Plan from 1929, known as Moerwijk-Noord, still followed the tradition of perimeter urban blocks used by Bakker Schut and Berlage. Dudok also discussed the relationship between open green spaces and open urban blocks.

‘I have never been a particular advocate of urban building strips, and I do see some advantage for the residents in the greater intimacy of a rear side. However, my heart goes out to the open and to the great and beneficent systematicness in the development of greenery, in which the greenery within the open urban block can certainly also be involved. I no longer accept the perimeter urban block, with its oppressiveness in the corner solution, in our time. But apparently, there is still a difference of opinion about this in our small country. It is not inconceivable that such differences will be able to live side by side and build a good enlargement plan together into a satisfactory whole. In my city plan for The Hague, for example, I offered a well-considered opportunity to do so.’ (‘Reflections on the work of the Study Group for Post-War Housing’, June 1943, quoted by Van Bergeijk, 1995: 115).

Dudok’s connection with history was a theme that had faded away since the fall of Cuypers and De Stuers with the new ideals of modernization in the interwar period, but it took shape again in The Hague with Dudok, Vrijenhoek, Van Gelder, Wils, and De Monchy. Perhaps the crisis years made us dream of better times. It was only after the war that the layout of what would later be called The Hague Southwest would really begin.

Aesthetic committee curtailed, De Monchy's power politics

‘My all-around green neighborhood / My never enough praised Haegh’

Van Gelder began his much-praised book: ‘s-Gravenhage 1935-1945 hoe het was, werd en worden moge (1946) with the above-mentioned quote from Constantijn Huygens, he described the green village character and the future development of The Hague.

However, the collaboration between the city council and the easthetic commission had cooled. The architects were no longer automatically serving the interests of Bakker Schut and his department, which caused resentment among the municipal executive (HGA bnr 828-01 Municipal Council 1953-1990 Inventory number: 10030). Opinions on the appearens of buildings in the council often differed. In a letter dated April 3, 1936, the munciplaity executive proposed to reorganize the easthetic committee (schoonheidscommissie) into a quality committee (welstandscommissie).

It was believed that this committee should have a diverse composition and should not be an administrative body. In a letter also dated April 3, 1936, De Monchy and municipal secretary Boasson explained the transition from an easthetic committee to a streamlined and limited quality committee. The alderman for Urban Development and Housing at that time was Vrijenhoek. The number of committee members had already been reduced from nine to six, and the mayor’s proposal further reduced it to three.

Although there was hardly any construction during the crisis years, there was still some activity. The municipality executive did not want to dissolve the entire committee, but councillor Guit submitted a motion to immediately abolish the entire committee. Some councillors, however, wanted to limit the committee’s powers with a second motion (HGA bnr 828-01 inv.nr.10030: Proceedings of the council, May 4, 1936). The old easthetic committee consisted of Mr. J.F. van Royen, A.J. Kropholler, B.C. van den Steenhoven, D. Roosenburg, Ir. A.H. van Rood, and H. Hoekstra. The last three would not be replaced until May 1, 1939, and the first three on May 1, 1937 (HGA bnr 828-01 inv.nr.10030: Correspondence municipality and architects and organizations).

The mayor and secretary argued in the letter that an aesthetic assessment could also be conducted by the officials of the BWT service (with the eternal rival of Bakker Schut, G. Meijer, leading the way) and that this could reduce delays and improve efficiency. Changing the members of the committee more quickly was also seen as a strategy for the board to diminish the influence and power of the committee: ‘In cases where there is a need for information, a small committee consisting of three construction experts, as mentioned above, could suffice outside the official context. They should be replaced periodically to prevent rigidity of opinion.’ (HGA bnr 828-01 inv.nr.10030: Letter of 3 April 1936 from De Monchy and Boasson: 1,2).

The municipality executive also proposed that the director of the Building and Housing Supervision Service determine which plans should be submitted to the committee for assessment. Not all plans were submitted to the committee in this way. Only after the pre-selection process did the committee issue a direct recommendation to the municipal executive. According to the proceedings of May 4, 1936, Councilor Van Beresteyn of the Vrijzinnige Democratische Bond (VDB) summarized the situation as follows:

‘As far as the matter itself is concerned, the whole history of the quality and aesthetic scheme has such a bitter aftertaste that, in the end, one does not get where one needs to be with this committee. Aesthetics is not produced by refusing what is ugly, but by architects who understand their profession; I am not saying that one should not say, ‘We do not have to keep out what is ugly, but we must not imagine that we are doing what we can with it’.’ (HGA bnr 828-01 inv. nr. 10030: Acts of May 4, 1936: 341).

There were doubts among council members as to whether it would be okay if all powers and tasks were shifted to the Building and Housing department and the aesthetics committee’s implementation was limited. Van Beresteyn also expressed his concern: ‘I am afraid to give such great power to Building and Supervision. It may not be that bad, but I’ve seen a few cases in which people said: it’s rubbish, it rattles all the way. If you want to know exactly what it’s all about, you only hear a few general terms, and I don’t think that’s right.’ (Ibid.: 342).

The quality would no longer be included in expansion plans, but Van Beresteyn objected to this: ‘Finally, a remark about the opinion of the minority of the committee, who are of the opinion that this quality committee should also judge and advise on the construction of the city. I also think it is of much greater importance that an extension plan meets the requirements of aesthetics than some house in a back street.’ (Ibid.: 342).

De Monchy, Vrijenhoek, Bakker Schut and Dudok thus seized power and gave Dudok space. In the future, the tasks of the quality committee would mainly focus on the buildings designated by the director of the service. This narrowing also meant a cutback; the committee no longer needed a separate office and secretary. Van Beresteyn also noted that the mayor and aldermen simply ignored the implicit criteria used in the assessment.

‘I now come to the main point, which gives me cause to earnestly warn against this system. My main objection to this is that the Mayor and Aldermen are extremely prone to overlooking the question of when something is contrary to quality.’‘ (Ibid.: 342).

The committee had to be able to justify a rejection, according to Van Beresteyn. This was prescribed in the old regulation, but it did not happen. Councillor Vliegen noted that this new lay out of the building was related to the arrival of Dudok in The Hague. He argued, ‘May I remind you that we have appointed Mr. Dudok, he is at work after all. At least we had a lot of expectations when he was appointed, and to put a committee above him now, where is the end? We’ll have to wait and see what comes of Mr. Dudok.’ (Ibid.: 347).

When looking for members for the new quality committee, the municipality reached out to various organizations to gather nominations. However, several important organizations were dismissive of these efforts. In a letter dated September 17, 1936, the BNA expressed its objection to the way things were being handled and refused to cooperate further in appointing members to the quality committee.

More protests from the city

The resistance was not limited to architects and council members. In a letter dated 16 September 1936, the Algemene Katholieke Kunstenaars Vereeniging also objected to this change: ‘… it seems to us that the Committee to be set up has very little say, but gives the impression to the outside world that it bears full responsibility for the interpretation of the quality provisions of the Building and Housing Regulations.’ She, too, did not want to make any proposals for members of this quality committee.

The Haagsche Kunstkring also strongly objected in a letter on September 8, 1936, refraining from cooperating with the municipality and refusing to nominate any members. Only the NIVA (Netherlands Institute of Architects) came up with a proposal. The Haagsche Architecten Club with ir. H. van Vreeswijk and W. Verschoor wanted to submit their own proposals and they requested a postponement in a letter dated August 18, 1936. After eight people were finally nominated, the director G.A. Meijer of the Municipal Building and Housing Inspectorate responded in a letter to the municipal executive on September 29, 1936. He stated that, in his opinion, only ir. H. van Vreeswijk would be suitable for the position.

In the end, Ir. A.H. van Rood, D. Roosenburg, and H. Hoekstra were appointed as members of the quality committee. As reserve members S.J. van Emden, J.W. Janzen, and Ir. H. van Vreeswijk were appointed. On April 1, 1937, the aesthetic committee was definitively changed into the quality committee. In a letter to the alderman dated 5 March 1943, a schedule was created outlining the resignation dates for members. Hoekstra: 1 April 1941, Roosenburg: 1 April 1943, Janzen: 1 April 1945. In 1941, Van Emden declined the position. The archives did not indicate why he resigned or whether this was related to his Jewish background. In April 1943, the NSB municipal executive abolished the quality committee and transferred its responsibilities to an ‘Advisory Council on Urban Expansion and Architecture’. Finally, two Hague architects from the Haagsche Architecten Club, H. van Vreeswijk and M.F. v.d. Gugten, who were both NSB members, were appointed as members of this council. The chairman of this council was dr.ir. G.A.C. Blok. After the liberation, this council was disbanded (HGA bnr 828-01 inv.nr.10030: Regeling inzake de toepassing van de welstandsbepaling der bouw- en woonverordening voor ’s-Gravenhage).

For an architect from The Hague like Roosenburg, who received few commissions as an independent architect in The Hague, the power politics of the communist hunter De Monchy (Harthoorn, 2011), with Bakker, Schut, and Dudok in the background, must have been experienced as offensive, to say the least. After the war, the conflict would take on grotesque proportions in the discussion about the future of the city. The cityscape in the minds of the interwar politicians, urban planners, and architects would come to be at odds with the ideas of a young guard with their own vision of images and the city. Dudok and Roosenburg played a central role in that conflict, and that conflict had more layers. At that time, the major expansion of the Escamppolder, Maepolder, and Ockenburg in what is now The Hague Southwest had yet to begin.

Post-war population pressure and housing shortage 1946-49

The Netherlands to 20 million inhabitants in the year 2000

During the crisis years and the war, The Hague was in a state of urban hibernation. In 1930, The Hague had 432,680 inhabitants, which rose to 520,875 inhabitants in 1942. However, a steep decline followed, and by 1945, the city only had 450,949 inhabitants. Due to the construction of the Atlantic Wall, parts of the city along the coast were evacuated, and Bezuidenhout suffered from a mistaken bombing. The war damage resulted in the loss of many beautiful neighborhoods and thousands of homes. Consequently, The Hague lost its former status as a chic and pleasant city, becoming a problem city with a housing shortage and a weak economy, which would remain vulnerable in the long term.

After the war, there was an explosive growth in the population. In 1947, there were already 523,703 inhabitants, in 1950, 558,849 inhabitants, and in 1959, the peak of 606,826 inhabitants was reached. After that, things went downhill for The Hague and its population size. The turbulent growth of new buildings in The Hague took place between 1950 and 1960 in Zuidwest and, after 1960, in Mariahoeve.

Despite the escalating conflicts, the cityscape of international significance and allure was realized there, especially in Mariahoeve. It became an iconic urban ensemble where all the lines came together during this period. The need to do something radical was great because it had been calculated that the Netherlands might have 20 million inhabitants by the year 2000. The Hague would have to absorb a part of that population. The conflict between Dudok (as the right-hand man of the city council) and Roosenburg (as foreman of architects and corporations in The Hague) focused on the question of what The Hague should look like in the future.

If Dudok’s ideas are the thesis, then The Plan 2000 is the antithesis, and Mariahoeve is the synthesis of mature urban planning and architecture. Dudok and Bakker Schut worked on the structure plan for The Hague, but in 1946 five young ambitious architects from the Roosenburg office, among others, presented a counterplan: The Plan 2000. It was a radical and impracticable student plan that incorporated all the novelties of urban planning and therefore seemed very useful for The Hague. Finally, this resulted in a synthesis of Mariahoeve where the ideas of Dudok and the CIAM came together again in a new relationship.

Thesis: De Monchy and Vrijenhoek's dictate to the council

Administrators such as Mayor De Monchy and former Alderman Vrijenhoek wanted to continue as they had been accustomed to before the war. They likely tasked Dudok with creating a reconstruction plan in late 1944 (Sluijs, 1989: 12,13). This plan focused on restoring the parts of The Hague that were devastated during the war, as well as proposing changes to the existing city area and creating new expansion areas. De Monchy, Vrijenhoek, and possibly other trusted members of the bourgeoisie were involved in the commissioning process. Dr. ir. Z.Y. van der Meer, a civil servant who would later become a member of the national Board of Commissioners for Reconstruction, was also likely involved (Sluijs, 1989).

After the war, the reconstruction of The Hague was discussed in the newly installed council on 3 December 1945. The regentious course of events of De Monchy and Vrijenhoek was met with quite a bit of criticism. Councillor Mrs. Bouma-van Strieland (PvdA) argued about the importance of the reconstruction plan: ‘If there is one thing now, after this war, that we can all agree on, it is that family life will have to be renewed and deepened. In my opinion, we can attribute the general depravity of our youth, the decline in the moral level, to a large extent to the dismemberment of families, to the fact that it is not possible, or only to a limited extent, to have a regular family life in a closed family, in a home of their own, in which the family can live as intimately as possible.’ The councillor argued that it was necessary to expand the advisory committee to include women, as they are ultimately the first to be involved in the design of the new homes to be built. The council member also advocated involving housing corporations in this advisory committee. The nine corporations in The Hague housed a total of 150,000 inhabitants. Furthermore, according to the council member, it was desirable for council members to be included in this advisory committee. For example, there could be more contact between the advisory committee and the council. Bouma-van Strieland also asked who had commissioned the architect Dudok to draw up a general construction plan.

It was revealed during the council debate that the municipal executive had already made the decision to do so, shortly after the war when the council had not yet been installed. It also became evident that it was not the municipality that had invited Dudok, but rather Dudok had invited De Monchy and Vrijenhoek to discuss the reconstruction of The Hague. Further investigations revealed that the municipal executive had commissioned Dudok to design a General Reconstruction Plan for The Hague, and on July 17, 1945, an advisory body was established by the municipal executive to provide guidance to Dudok. This advisory committee included representatives from the state, the municipality, and various groups such as the middle class and industry.

Other council members also suggested changing the members of the advisory committee. The objection raised by councilor Van Praag was: ‘… Is it really desirable that not only the plans for urban expansion, but also for the improvement of the city, the solution of various old problems, in which the whole of The Hague, which has been so violated, is being rebuilt, should be placed in the hands of a single architect who works together with the Mayor and Aldermen?’

Van Praag argued in favor of involving the architectural community of The Hague. These architects were also not represented in the advisory committee, even though they had to carry out the plan for the most part. Representatives from the architects’ organization in The Hague should be involved in the development of the plans in consultation with them. Council members voiced their criticism of the closed nature of the advisory committee on urban planning and called for more openness and citizen, colleague, and council involvement.

The mayor didn’t think it was necessary to expand the committee. De Monchy gave the assignment to Dudok and wanted to keep the advisory committee as narrow as possible, with broad powers for Dudok and the committee, without involving The Hague’s architects, housing corporations, and housing consumers. The directors of Municipal Works and Urban Development were represented in the committee. De Monchy argued:

‘On the other hand, I would like to give the committee a very broad authority with regard to the various questions, and this includes not only the construction of the destroyed districts and the expansion of the city outward, but also internally: the improvements that must be made in the city, the reconstruction of The Hague as necessary to regain its former status as a city of international significance and allure in the coming decades. We hope that The Hague will soon become once again the city of international significance and allure.’

The international significance and allure that De Monchy spoke of could only be realized with Dudok as a figurehead, but there was little support among the council and the architectural community in The Hague. Mayor De Monchy emphasized that Dudok was an architect of international stature and that he knew The Hague well. De Monchy and the municipal executive would have preferred one architect to be on the advisory committee (also known as the ‘urban planning committee’) to exchange ideas with Dudok about the plans, but it was eventually decided to set up a contact committee of five architects. But the council eventually decided on a contact committee of five architects. However, the mayor immediately indicated that, ‘… We didn’t want to commit ourselves to associating with the architects as consultants…’

In consultation with the local BNA circle, five architects were proposed, called The Council of Five, who were assumed to carry out the reconstruction plans for a large part. This council consisted of: Kees Abspoel, Julius Luthmann, Dirk Roosenburg, Romke de Vries, and Henk Wegerif. The last architect, in particular, stood for the line De Monchy, Vrijehoek, Van Gelder, Dudok. However, this sounding board group of authoritative architects from The Hague was ignored by Dudok.

During the debats in the city council on December 3, 1945, the mayor gave the impression that the architectural community of The Hague had resigned itself to this situation. In this way, the mayor, aldermen, the Department of Urban Development and Housing, and Dudok were diametrically opposed to the council, the citizens, the housing corporations, and the architectural community in The Hague.

The later director of the service, and then still young urban planner, Van der Sluijs, outlined the relations between the Department of Urban Development and Housing and the architects in The Hague at the time of the conflict. He explained that the architects in The Hague were unpleasantly surprised by the assignment. They had hoped to finally be able to work on their own city. The pioneers of the Kring Den Haag of the Association of Dutch Architects (BNA) had little appreciation for the Department of Urban Development and Public Housing. Likewise, the department seemed to have little appreciation for the architects. The service systematically passed them by, except when it had specific commissions to give. For example, the department, which also included the municipal land company, issued land on a long lease with the condition that the buildings would be based on a sketch design provided by the department. The architect Co Brandes, who was from The Hague, had by far the lion’s share of these sketch designs. However, his close collaboration with the many self-builders in The Hague, and his only provision of drawings required by the Building and Housing Inspectorate, made him little appreciated by his colleagues. As a result, large parts of Marlot and Bohemen-Geest van Gogh were created. (Sluijs, 1989:13).

Many architects from The Hague were deliberately excluded by P. Bakker Schut. Vrijenhoek did not become an alderman after the war; his old post was taken over by alderman Feber in 1945. In 1947, De Monchy resigned as mayor and was succeeded by Willem Visser of the Christian Historical Union, who had to resign in 1949 because of a foreign exchange affair. De Monchy, the administrator who supported Dudok, was no longer by his side. It was time for a reckoning. The conflict deepened, and Dudok and Bakker Schut found themselves alone with the service.

Antithesis: The Plan 2000

Two ideas about cityscapes came into sharp contrast: the ideas of De Monchy and Dudok about the continuation of the past and the character of the city (supporters of the Schoone Stad), and the new insights according to the CIAM with their own supporters. Given the housing shortage and war damage, it was not surprising that after the war, the debate on this subject became emotionally charged. Reconstruction was high on the agenda. The discussion between Dudok and Roosenburg was not only about stylistic differences (brick or concrete, brown or white), as is often posited with great aplomb in architectural books or about personal issues. In the discussions, it became clear that completely new insights had emerged in the field of urban planning to meet the presumed explosive growth of the population. Reconstruction was an urgent issue and also a great opportunity to realize old ideals or to test new ideas (Freijser et al., 1991: 113). Perhaps the new cityscape was the continuation of the old.

Dudok biographer Van Bergeijk spoke of a cliché that had been portrayed by, among others, Van den Broek and Le Corbusier: ‘The orthodox modernists stumbled over the freedoms that Dudok allowed himself. The form would have been elevated above the function. The technology of building would not be sufficiently public.’ … ‘But the view of Dudok as a late romantic is more than ever a cliché, which was only used to obscure his significance and his architectural qualities’ (Van Bergeijk, 1995: 7).

The terms ’traditionalists’ and ‘modernists’ were often used because they were the names of those movements during that time period. However, both cityscapes had unmistakably emancipatory intentions within their context and can both be seen as variants of modern architecture and urban planning (Van der Woud, 1997).

Architects in The Hague have long debated the distinction between the ‘brown or brick modernists’ and the ‘white modernists’. This comparison contrasted the modern movement of the interwar period with the modern post-war architects. However, this contradiction is flawed, as evidenced by documented reconstruction projects in The Hague that utilized a substantial amount of brown or yellow brick (Valentijn et al., 2002). In reality, one tradition evolved from the other, and Dudok, despite being labeled as a supporter of traditionalism due to the conflict in The Hague, actually served as an intermediary figure. The controversy was about the difference in the cityscape: the spatial motives, the buildings and the urban spaces. Dudok aimed to maintain control over the final image, while the CIAM, Het Plan 2000, and Cornelis van Eesteren believed the final image should emerge from a process.

Post war reconstruction and new neighborhoods had the highest priority, and the five young protagonists of the CIAM offered a growth strategy with The Plan 2000 that the municipality could not ignore. The Plan 2000 did not aim for a final expansion plan of the municipality (with an explicit image) but instead proposed the phased implementation of neighborhoods over a longer period of time. It also divided tasks according to scale level between urban planners and architects, as well as sought to protect the monumental inner city by constructing an inner ring road. This would involve replacing everything outside of this ring road.

However, Dudok had already proposed that the layout of new neighborhoods should be carried out in parts over a longer period of time and by various architects in the Nota van Toelichting op het Ontwerp-Uitbreidingsplan voor het Zuid-Westelijk gedeelte der Gemeente ’s-Gravenhage [Escamppolder, Maepolder en Ockenburg] (1936).

With The Plan 2000, the city was given a volcanic cross-section with the old city and the ring road in the crater, then high-rise buildings and then descending in height to a sharply defined city edge with towers as markings. The city was also given a pure dartboard shape as a map with the old city center surrounded by roads right in the middle. The residential areas followed Perry’s neighborhood unit idea (1929, 1939).

Dudok had a different vision. He aimed to enhance the open village character and avoid creating sharp boundaries that would reinforce long lines with through roads. His goal was to reinforce The Hague’s typical green character. Berlage also shared this intention with his plan from 1908. In The Plan 2000, the city was distinctly separated from the countryside.

The conflict was also about the inner city. Unfortunately, the main roads and breakthroughs in Dudok’s plans did ruin the historic city center, which met with great resistance from articulate and influential citizens. This was already the case with Berlage and Lely (Van Liefland and Lindo tried to save what could be saved), and with Dudok, it was now taking place on an even larger scale. Organizations such as the committee Het Hart voor Den Haag, in which all the notables had united, and even the director of the Cabinet of Queen Wilhelmina was represented, turned against Dudok’s intention to sacrifice the city center.

Dudok was supported by Piet Bakker Schut senior, while his successor in 1949, his son Frits Bakker Schut junior, sided with Het Plan 2000. During a debate at the Kurhaus in 1949, Dudok’s structure plan was presented, while just before that The Plan 2000 had been published in book form with a foreword by Cornelis van Eesteren. Dudok’s work was praised in the council, but the structure plan was not accepted by the municipality council.

In the end, a mixture of ideas formed the foundation for the planning of Southwest that left no one satisfied: Dudok’s concept of an open green continuum with expansive green areas, The Plan 2000’s proposal of ring roads, high-rise buildings, and neighborhood ideas, as well as phased implementation and the division of tasks between urban planners and architects, and Van Gelder’s proposal for neighborhoods to have all necessary facilities. The result was that The Hague ended up with mega neighborhoods in Southwest, each accommodating between 30,000 and 40,000 residents per neighborhood. As a response to the failure of Southwest, the concept of Mariahoeve was developed and laid out after 1960.

Synthesis: Mariahoeve

The young urban planner, Frits van der Sluijs (1919-1989), and the chief architect-head of the municipal housing service, Fop Ottenhof (1906-1968), who witnessed the entire conflict up close, designed the Mariahoeve district after an excursion in Scandinavia. It was an elegant synthesis of the urban planning and architectural ideas of Dudok, Het Plan 2000, and Friedhoff. Mariahoeve was not only a tribute to The Hague’s leafy greenery and a reevaluation of the landscape, but also a public housing experiment that aimed to mix residents from different socio-economic backgrounds. Numerous new building typologies, influenced by Piet Zanstra (1905-2003) and others, were introduced and constructed in a Hague variant of modern brick architecture. For years, Mariahoeve became the iconic urban ensemble that the Roman Catholic-Red coalition in The Hague took pride in. The green village character was preserved thanks to the creative work of young urban planners and architects, resulting in a beautiful synthesis.

The conflict over the future of The Hague, Dudok's structure plan

The fuse in the powder keg: The Hague Builds Up exhibition (1946-47)

The smoldering conflict came to an explosion with the exhibition where Dudok’s reconstruction plans were presented: ‘The Hague Builds.’ The exhibition of lectures and debates at the Gemeentemuseum lasted from 24 December 1946 to 26 January 1947. In the catalogue, The Hague Builds Up, the organizers sketched an optimistic and fresh picture of what had to be done in the battered city (Knuttel, Dudok, & Wegerif, 1946). The exhibition committee included all the important people from the architecture and urban development in The Hague: P. Bakker Schut, Dudok, and Suyver, and the architects Buys and Roosenburg were also present, as well as many other committee members. Prominent in the exhibition were two of Dudok’s plans: the Sportlaan-Stadhoudersplein-Zorgvliet Plan and the Bezuidenhout Plan, including the government center (Dudok, 1946). The young, ambitious architects of The Plan 2000 from The Hague were also members of the committee. This group, J.J. Hornstra, J.G.E. Luyt, J.N. Munnik, H.C.P. Nuyten, and P. Verhave, previously presented an alternative to Dudok’s plans for The Hague.

The Plan 2000 ended up being the most drastic, innovative, and disruptive growth strategy in The Hague’s history. However, this plan couldn’t simply be disregarded as a strange utopia; it presented many completely new ideas and insights that proved to be very valuable in the reconstruction process. For Dudok, Vrijenhoek, and De Monchy, this was an unpleasant situation.

These five young architects were no strangers to each other. From 1940 to 1962, Roosenburg had a partnership on Kerkhoflaan with Verhave (businessman and negotiator), Luyt (the designer), and De Iongh. Luyt had studied at the ETH in Zurich and introduced new ideas, while Roosenburg was the experienced master who secured the projects, and Verhave ensured their realization. The architectural office LIAG in The Hague would later emerge from this office (Hornstra, Luyt, Munnik, Nuyten, & Verhave, 1949) (Hoogstraten, 2005).

The excitement at the exhibition was immediately palpable. The chairman of the committee, Dr. G. Knuttel, tried to reconcile the divergent points of view in the introduction to the catalogue accompanying the exhibition. He mainly defended Dudok and argued that, in addition to the usual functional requirements, society also benefited from a clean appearance. For him, the cityscape and the city as a whole, and the buildings separately, were still works of art brought together in a harmonious group.

It is striking that the contrast was reduced to a difference of opinion about ’the beautiful’, and thus relativized to a subjective experience, while with The Plan 2000, a whole series of new urban planning insights was presented.

The chairman cleverly used the terms ’traditionalism’ and ‘modernism’, which do not overlap. Beautiful architecture versus modern utilitarian architecture. For the chairman, architecture had, first and foremost, a social function, and it had to meet the most practical and primary requirements. Following Berlage and later Dudok, he emphasized: ‘We architects want to serve.’ A non-committal statement, as, after all, the CIAM also only wanted to serve. What architect didn’t want to serve? Implicitly, the chairman meant that the CIAM architects did not want to serve in the kingdom of P. Bakker Schut, and Dudok. It was too easy to ignore the fact that many architects wanted to serve during the interwar period, but they were excluded from building production.

In the catalogue, Knuttel also pointed out another problem that now revealed itself, namely the coherence between the building objects as a condition for a beautiful city (Schoone Stad). The German urban planner Brinckmann was mentioned as well. Perhaps Knuttel foresaw the consequences of thinking according to the CIAM pattern. In the exhibition catalogue, Dudok also warned against the fragmentation of the city into separate building objects, which is understandable because many of the building plans on display were wonderfully beautiful (e.g., by Romke de Vries) but inward-looking. Dudok argued: ‘But a collection of beautiful flowers does not make a beautiful bouquet: one must understand the art of flower arranging.’ Berlage’s ideas about Gesamtkunst were illustrated by Dudok with the bouquet metaphor. He also stated that The Hague was facing an entirely new problem. Nowhere else had the city been able to demonstrate on such a large scale that it was up to this enormous task: to build a beautiful city (een schoone stad te bouwen). Dudok repeated his vision as he would later include it in the explanatory notes:

‘But I would like to emphasize once again that a good and beautiful city no longer arises by chance from more or less good and beautiful buildings, but that it makes certain autonomous demands which we can only meet through very harmonious cooperation. Life is short; the house outlasts man, but the city outlasts the house. The city plan encompasses the constituent buildings and spaces in terms of both time and form (Den Haag Bouw op, 1947:13).’

One of the fallacies that was used, after all, the architects of The Plan 2000 were not against it either. They only felt that this was the task of the architects who elaborated on the neighborhoods, not the urban planners. Architects from The Hague felt that Dudok, as an urban planner, was working on an architect’s final plan for The Hague and that he wanted to control the entire cityscape. They believed the detailed descriptions of materials and imposed shapes went too far.

Dudok’s Beautiful City still reflected ideas from the interwar period and did not address the problems of our time, it was argued. It was said that Dudok did not understand the desirable concept of neighborhoods or neighborhood unit that the municipality had in mind for the city’s structure plan. The new city required a different vision. Not The Beautiful City with a final image to solve the city’s problems, but a radical and grand vision based on research and the dynamics of the city – a phased plan with an open-ended image that would only reveal itself in the future. It was an ambitious goal.

The contrasts between Dudok’s ‘The Beautiful City’ and the CIAM’s ‘articulated and divided city, with the neighborhood units and the ring road’ became painfully clear at the exhibition. The gulf between the two cityscapes was deep. On August 22, 1947, Dudok presented the city council with the final draft structure plan. Dudok opted for an orthogonal road structure that was considered appropriate for the nature of The Hague, in contrast to Het Plan 2000, which had opted for ring road access.

The city as a volcano: The Plan 2000

Why did a utopian student plan, which even Van Eesteren considered unfeasible, have such a great influence on the development of The Hague? It was not just the plan itself, but rather the modern ideas of urban planning and architecture that were described in it, as well as the preservation of the historic core. The plan focused on the gradual development of the city over time, with districts and neighborhoods being built individually, each with its own design. This growth strategy ultimately shaped the cityscape of The Hague.

The cross-section of the city was particularly striking and resembled that of a volcano. In the middle of the crater with the historic center and its monuments. Then, there was an inner ring or dividing ring around that center with high-rise buildings on the outside of the ring. This configuration helped relieve the traffic pressure in the old city within the ring road. The buildings within the ring road were limited to a maximum building height of 20 meters, while the buildings from the inner ring to the outside could be higher, reaching 30 meters, sloping towards the outskirts of the city. The residential areas were built on the volcanic slopes, with towers on the outskirts of the city bordering the meadows. Here is an overview of the most important innovations:

- No final image in the planning in general.

- There is no overall plan, but rather a growth strategy that architects fill in with contemporary architecture.

- The planning is done by different scales: structure plan, district of neighborhood plan, and detailed plan.

- The structure plan now also covers the already built-up area, whereas previously it only applied to areas outside the built-up area.

The focus was now also on the existing city. A ring road was built around the city center to direct traffic along the city instead of through it, aiming to protect the historic city center. Nowhere was the separation between the disciplines of urban planning, architecture, and public housing more consistently implemented than in The Plan 2000. The various disciplines were scientificized. Another crucial point was the monumentalization of the city center. This meant that everything within the inner ring road was elevated to monument status, while everything outside this ring could be replaced by modern and contemporary buildings.

After the plan was presented at the 1946 exhibition, a detailed explanation immediately followed in the journal Bouw (Vol. 2, No. 8, 22 February 1947: 58-67). In 1949, Het Plan 2000 was published in book form with beautiful drawings and typography. Cornelis van Eesteren, the chairman of the CIAM and professor of urban planning in Delft from 1948 to 1957, wrote the foreword. He pointed out that the clear structure and harmonious form were particularly convincing. It was a radical and utopian plan that everyone saw would never be implemented.

Van Eesteren noted that the concepts of growth strategy and division of labor after scale had originated in London during the war period, when the MARS Group conducted studies on the urban structure of the city. The MARS Group (Modern Architectural Research Group), a think tank for modernism from 1933 to 1957, consisted of architects and critics such as Maxwell Fry and Morton Shand. The MARS Group advocated for ‘period planning.’ Through this growth strategy, the architects aimed to revitalize The Hague while also establishing a clear division of responsibilities between urban planners and architects. The entire process was divided into three stages: the structure plan (which included building types, main traffic networks, and green areas), the Neighborhood Plans (which defined key buildings, main roads within each district, and building heights and densities), and the Detailed Plans, which would be created by future architects in accordance with the prevailing architectural trends. No specific visual representation was predetermined for these plans.

In Dudok’s plan, traffic raced right through the city center, over the Voorhout, through the Willemspark, or cut through the Grote Marktstraat. ‘Today’s expansion plans were by no means as ingenious as The Plan 2000,’ Van Eesteren remarked, and the problems in the city are considerable. The Housing Act stipulated that municipalities had to draw up structure plans for outside the built-up area, but there was no innovation within the built-up area. Nevertheless, a rejuvenation process had to be initiated there as well, according to Van Eesteren.

He went on to state that ‘ ‘The Plan 2000’ arose from the conviction shared by many, including the designers, that one must aim for a shared and well-considered vision in order to perceive the form and essence of the city body as a whole and its various components.’

This shows that the ideas about Gesamtkunst had not been completely abandoned. Another old idea also resurfaced: the young architects emphasized the importance of the cityscape. ‘The human eye and mind require variety, accents, and clarity. The disregard of these requirements has led to our desolate and confusing masses of houses. One of the main points of our research was, therefore, to create an articulated city that forms a harmoniously clear whole.’

However, the task set by the architects from The Hague went much further than Dudok’s plans. ‘Above all, it must be a structure plan for the whole,’ according to the architects of The Plan 2000, and not just for the parts affected by war damage. The architects stated: ‘Only when beauty and practicality unite into a harmonious living whole, the ideal is achieved.’ The problem of the city, according to the group, was: ‘To create an organically constructed orderly city in which all elements of city life can come into their own. The possibility of this must be created in the plan.’

The solutions that were proposed were the neighborhood concept (De Wijkgedachte), a concentric growth, open buildings for light and air, separation of traffic types, lots of greenery for recreation, and one clear city center. And the means that would provide a basis for good urban development were a survey, a structure plan for the entire city (existing and new), and then the elaboration in phased district and detailed plans with a gradual remediation of old city districts.

The center within the ring road was considerably smaller than the historic center within the canals. There were mainly mixed-use buildings intended for government, culture, entertainment, and some residential buildings. It was a city center primarily focused on providing services. The plan was to eventually replace all buildings that had no cultural or historical significance with new constructions. The average age of the houses was estimated to be around 100 years. For the architects, this fact justified intervening in the existing city structure through expropriation, demolition (referred to as remediation), and new construction. When people thought of remediation, they usually associated it with cleaning up the worst slums. However, the young architects also aimed to improve undesirable situations in the existing street plan and buildings. According to them, it was a question of principle. Too often, reconstruction and expansion plans were based on the assumption that the existing situation could remain unchanged. This approach would lead to negative impacts on the new parts, making improvement impossible for at least a hundred years.

The Hague, as a city with the characteristics of a volcano, held a dominant role in urban development until 1980. This was due to a combination of factors, including the city’s international reputation, its growing allure, and the ambitious plans for expansion. The administrators, as well as the citizens, were lured by the idea of turning The Hague into a truly global city. However, they failed to consider the detrimental impact this plan would have on the residents and the historic old town. This lack of foresight is understandable, considering the local administrators’ belief that the Netherlands would have a population of 20 million by the year 2000.

Open letter to the city council (18 January 1947)

In an open letter to the municipal executive and council of The Hague, the architects of the Council of Five, appointed by the municipality, vented their frustrations about the difficult collaboration with Dudok, according to the journal Bouw (Vol. 2, No. 3, 22 February 1947: 17-18). The opening speech at De Monchy’s exhibition and Dudok’s speech were both rather polemical, which prompted the architects to inform the city council about the actual state of affairs with Dudok. The Council of Five wrote that, for opportunistic reasons, Dudok had not been commissioned by the municipality to involve the entire city in the study. The council considered it a serious omission on the part of the municipality that no development plan had been made for the entire city, but only for parts of it.

This had been emphasized by architects long before the war, even by the Aldermen Feber, who is now in charge. The municipality also failed to clarify the issues, and it was thanks to Dudok’s personal competence as an architect and urban planner that the urban development plans were of much better quality than those produced between 1918 and 1940. The architects from The Hague also believed that it was crucial to start thinking about developments for the next fifty years. The municipality should clearly indicate the starting points for a structure plan. For example, no decisions had been made regarding issues such as the location of crossroads, the cultural center, and the shape of the neighborhood concept.

With regard to Dudok’s Bezuidenhout Plan, the working group noted that the construction of the underground station restored the connection between the Bezuidenhoutkwartier and the city centre, but that car traffic was now routed through the city. The new station, the new ‘Regeeringsplein,’ and the city are all on a single line along the route. Traffic was forced through ‘De Groote Marktstraat’ between the Bijenkorf and Peek and Cloppenburg. ‘De Groote Marktstraat’ is a shopping street where the large department stores are located. Such a street was not supposed to be a thoroughfare. The second connection of the ‘Regeeringsplein’ via the Amsterdam Veerkade can never become significant as long as Het Heilige Geest-Hofje is at the end of it. The ‘Regeeringsplein’ was not meant to be a link on a main thoroughfare.

The Council of Five also criticized the location where the cultural center had been envisioned by Dudok, along the Stadhouderskade. You can’t expect the city to be enlivened in the evening, as the city center becomes a dead office city. The Sportlaan-Stadhoudersplein-Zorgvliet Plan lacked the obvious access road that connected the City Council Center on Javastraat and the International Center with the Peace Palace, the seaside resort of Scheveningen, and the Government Square. Incidentally, the criticism of the location of the cultural center also applied to the plan of Wegerif (one of the Council of Five) and Van Gelder. The architects from The Hague also missed the realization of the neighborhood unit or idea in Dudok’s plans, an idea that was essential for the future development of the city, according to the Council of Five.

‘Had this idea been taken as a basis, the buildings of social and cultural significance would not have received the random-looking distribution that can now be observed in the plans.’

Votes for and against the Dudok plan (18 January 1947)

However, Dudok also had supporters. J.H. Albarda wrote in the journal Vrij Nederland that Dudok understood the character of The Hague in his plans. The journal Bouw also listed the arguments of the proponents and opponents and quoted Albarda from Vrij Nederland: ‘In this quiet, clean city, there are no fantastic solutions. The designer is too realistic for that, by the way.

This large, characterful village (this is too often misunderstood) does not like the grandeur of huge tower houses or the harshness of densely and highly built-up neighborhoods. Here, the new parts should also provide an openness with lots of greenery. As a residence and seat of government, the city should give a prominent place to government buildings. Important traffic objects should not occupy a conspicuous place in this quiet city. The old core must be spared and preserved.’ (Bouw, Vol. 2, No. 3, 18 January 1947: 19-20).

Albarda also wondered whether the much-discussed neighborhood idea could be seen as ’typically The Hague’. Wouldn’t community life be more appropriate in Rotterdam or Amsterdam, he suggested. Finally, Albarda warned that the traffic problem should absolutely not be neglected, but neither should it be the starting point. First and foremost, a city was there to live, to work, and to relax.

The urban planner W.F. Geyl, who provided the municipality with a preliminary advice on the preparations for Dudok’s structure plan, was less positive and wrote the following: ‘First of all, however, it must be stated that it is an architect’s plan, which has little to do with urban planning…. And more importantly, how can an imposed unity of style that goes against the spirit of the times be real? Unity of style is only possible with unity of lifestyle…. What right does one have, for the sake of aesthetics, to prescribe one style and exclude others? … Every urban planner reflects their time. Dudok thinks that his own reflects the future tense: in fact, his attitude is aristocratic, to avoid the tainted word ‘dictatorial’…. We are entering the as yet undefined borderline between what the democratic majority can and cannot demand of the minority….’ (Bouw, Vol. 2, no. 3, 18 January 1947: 19-20).

A criticism that was harsh and direct, and stood up for the architects from The Hague, but, as Geyl continued, the objections of a planning nature are much more serious. There was no trace of the neighborhood idea desired by the municipality. The articulation in the city was lacking. Thoroughfares intersected neighborhoods and the Government Center. The cultural center that was built outside the center was disastrous for the city. Art and culture belong in the middle of life in the city center, according to Geyl. There was no need to repeat the stupidity of the Gemeentemuseum, which was built in a suburb.

Geyl did call The Plan 2000 by the architects from The Hague an urban development plan that The Hague could use in the future. This plan took into account the dynamics of the city and its social content and seized the opportunity that was now offered to us to make a start on a social urban reconstruction of The Hague, according to Geyl.

The series of lectures that followed in January 1947 as part of the exhibition widened the gap even further. As early as 11 January, Ir. A. Bos, director of the Dienst voor Volkshuisvesting in Rotterdam, gave a lecture on ‘Neighbourhood Concept and Urban Development’. On 17 January, Dudok spoke about his two plans for the reconstruction of The Hague. And on 24 January, a lecture was given by The Hague architects Verhave, Luyt and Hornstra about The Plan 2000, and everything that was wrong with Dudok’s plans.

The exhibition The Hague Builds Up (1946-47), the preliminary recommendations on the structure plan and letters and articles submitted to journals brought two veterans of The Hague architecture from the interwar period into even more conflict with each other: Dudok and Roosenburg. In the years that followed, the struggle developed in journals and local newspapers to its climax in the Kurhaus in January 1949.

Crisis at the Department of Urban Development and Housing and the birth of the Department for Reconstruction and Urban Development

The whole situation of the reconstruction was also exacerbated by the fact that the Department of Urban Development and Housing (Dienst der Stadsontwikkeling en Volkshuisvesting) in The Hague was in crisis and had become rudderless. In 1942, P. Bakker Schut, the major public housing provider of the interwar period, was succeeded by his deputy director Henk Suyver. Van der Sluijs remarked that incidents during a purge procedure concerning Suyver due to the war must have been to blame for the poor relations within the service. In 1945, even before the liberation, the retired P. Bakker Schut was hastily recalled to take over the leadership of the new municipal Reconstruction Service, which was established on 16 June, until 1949 (Huik, 1991).

The service had three main tasks: urban development, land management, and public housing. Suyver’s position was reduced to urban development, while ir. A. Lodder managed the land company, and ir. J.P. van der Ploeg managed the public housing. In 1946, Lodder and Van der Ploeg were appointed deputy directors, but relations within the management were poor (Sluijs, 1989). After some time, relations between Dudok and Suyver also became bad, and contacts were made through employees. The cooperation between the service itself and Dudok, on the other hand, was excellent, according to Van der Sluijs. Nevertheless, the municipal council regularly received a letter from Dudok with advice, followed by a counter-advice from Suyver. These circumstances led to a thorough reorganization of the service after the departure of P. Bakker Schut in 1949 and a further reduction in the position of director Suyver. The service was now split into three departments and given a new name. The Department for Reconstruction and Urban Development (Dienst voor de Wederopbouw en Stadsontwikkeling WOSO), the Municipal Land Company (Gemeentelijk Grondbedrijf), and the Municipal Housing Service (Gemeentelijke Woningdienst)

The director of the National Planning Office, dr. ir. Frits Bakker Schut, the son of P. Bakker Schut, was put in charge of the Department for Reconstruction and Urban Development. Additionally, he was given coordination responsibilities between the other two departments and was appointed Chief Director.

F. Bakker Schut was an outspoken supporter of the CIAM and soon found himself in direct opposition to Dudok. Van der Sluijs remarked about himself: ‘My position remained that of liaison, now between Dudok and Bakker Schut. It soon turned out to be that of a buffer as well because the newly appointed man also had his views’ (Sluijs, 1989: 16).

The commission for the congress building, which Dudok had been promised, went to Dudok’s old friend Oud through the efforts of F. Bakker Schut. According to Van der Sluijs, it was mainly the conflicts with F. Bakker Schut that led Dudok to return the assignment to the municipality of The Hague on 1 July 1951.

Quality Committee, supervisors and the Committee The Heart of The Hague

After the war, the pre-war quality regulation was declared in force again until a new framework was introduced. This framework was renewed annually. Three members were reappointed: H. Hoekstra, Roosenburg, and J.W. Janzen. The ‘Regulation on the Application of the Quality determination of the Building and Housing Regulations for The Hague’ ‘(Regeling inzake de toepassing van de welstandsbepaling der bouw- en woonverordening voor ‘s-Gravenhage) from 1937 was eventually used until the revision in 1954. This regulation of only three pages did not set out any criteria for assessment; it merely described procedures. In a letter dated 17 March 1954, from Mayor Schokking to the Quality Committee regarding the abolition, it was stated that the regulation no.6 from 1937 was no longer applicable. At that time, the three architects from The Hague, Hoekstra, Roosenburg, and Janzen, were still members of the Quality Committee. These three were several times member, from the beginning of 1936 to 1954. Van Emden also returned to the committee after the war (HGA bnr 828-01 inv.nr.10030: Regeling inzake de toepassing van de welstandsbepaling der bouw- en woonverordening voor ’s-Gravenhage).

Step by step, a municipal supervisor will be placed between the Quality Committee and the architects. In a letter dated June 5, 1950 from the archive it says. ‘The Chief Director informs that a provisional (emergency) measure has been taken for certain reconstruction plans; a supervisor has been appointed for this purpose.’ The Council of Five’s consultations with other architects about the new building quality regulation came to nothing because other architects opposed this regulation. ‘The chief director argues that the work of any quality committee is not satisfactory, because such a committee, whatever it may be, does negative work. The work of Supervisors is positive, they actively consult.’ Supervisors would play an important role in the reconstruction plans in the 1950s, until the council put an end to this in 1960 (HGA bnr 828-01 inv.nr.10030: Notitie van 5-6-1950 met betrekking tot de verlenging van de welstandsregeling).

But there was more going on in The Hague. Citizens who had been pushed aside by the city executive and who mainly wanted to emphasize the distinguished character of the royal city had organized themselves into the Committee The Heart of The Hague between 1947 and 1953. There was every reason for this, after all, the Quality Commision of The Hague could not be counted on. The urban planners of The Hague were not of much use either, and only the young architects of The Plan 2000 offered resistance and perspective (HGA bnr 656-01 Comité ‘Het Hart van Den Haag’, 1947-1953 inv.nr.:1-6).

‘In December 1946, a committee was formed here in the city with the aim of maintaining the special character of the Heart of The Hague, particularly around the Hofvijver, which possesses a charm like few other city centers. The committee also sought to accentuate this charm whenever necessary.’ According to the committee, The Heart of The Hague needed to regain its typical, stylish character, reminiscent of The Hague’s old center of government. They wanted to rectify past mistakes, such as the tram track that awkwardly passes through the gate of the Binnenhof. The committee believed that The Hague gave off a neglected impression.

This committee consisted of several prominent figures from the cultural world in The Hague. It primarily constituted of influential citizens rather than city administrators or architects. Among these notable inhabitants of The Hague were professor dr. J.G. van Gelder and dr. J. Kalf, who would become involved in the debate regarding the city’s future between Dudok and Roosenburg. One would expect the committee to support the ideas of Dudok, De Monchy, and Vrijenhoek, and work towards restoring the old values of the interwar period.’

According to the committee, the root of all the problems was the increase in traffic, which was increasingly ruining the specific character of the heart of The Hague. Dudok, who in 1949 had drawn three variants for east-west cross-connections (major traffic routes) through the heart of The Hague, came into conflict with the committee. In the report, this was a negative assessment of the structure plan. In one of the variants, it was proposed to widen the Kazernestraat to the Parkstraat for the benefit of traffic. The committee asked the mayor and aldermen to refrain from doing so. The committee proposed laying the connecting road more to the north in the extension of the Benoordenhoutseweg, along the Nieuwe Uitleg. However, the committee’s request was rejected on financial grounds.

Nevertheless, the municipality did not seem insensitive to the arguments of the committee, as reported in the annual report: ‘In the meantime, the Dudok plan, as far as the breakthrough is concerned, seems to have been shelved for the time being, and people are now more inclined to a main route via Javastraat or Mauritskade.’ Instead of the Lange Voorhout, the Willemspark was now ruined. The committee complained about the traffic interventions around the Binnenhof in several letters to Suyver of urban development and to the city council.

In an undated draft letter, presumably dated 12 October, to the municipality executive, the committee expressed its great concern about the idea of situating the government center on the site of the deer park or the Haagse Bos, an idea proposed by government architect Friedhoff and architect Luyt. The committee strongly opposed any encroachment on The Hague’s green city entrance. The proponents of this plan argued that ‘the deer park would be a strange sentimental ‘relic,’ a forgotten and lost corner.’

In another undated letter to the members of the city council, the committee wrote: ‘that the plans of the architects Friedhoff and Luyt for a new Government Centre would harm a great interest in The Hague because the Bos – which also includes Malieveld and Koekamp – would be affected.’ The committee indicated that it received a great deal of support for the objections, and as a result, the plan did not go ahead.

Was it the invisible powerful hand of the committee or was it public opinion in the city? It has been established that the committee had a clear image of The Hague as a representative city, and its members consisted of the city’s notables. Perhaps Queen Wilhelmina and, after the change of throne, the young Queen Juliana were personally informed about the state of the city by her director of the Queen’s Cabinet, Mrs. Tellegen, who was a member of the Committee The Heart of The Hague.

The pillarization variant of the neighborhood unit

It was not only a personal conflict between two architects of significance, or a generation gap, a disorganized municipal service, a quality committee acting like a secret service, the indecisiveness of SDAP ideologue Van Gelder, exclusion of anyone who wanted to be involved in the reconstruction, and a difference between new and old urban planning insights. The conflict had layers of complexity and acquired its own dynamic, continuing to cause trouble. To outsiders, this may have appeared as an intricate web of interests, sensitivities, and nitpicking. In the end, the conflict centered on the interpretation of the Anglo-Saxon neighborhood unit (De Wijkgedachte). All the architects and urban planners found themselves standing together and opposed to Van Gelder, who aimed to enforce the sectarian division of the neighborhood unit.

The Social Democratic Party, PvdA, and the Catholic People’s Party, KVP, both part of the municipal coalition in The Hague, were the leading parties during this period. Politically, the period between 1945 and 1960 was a stable time for the city, with the social democrats and the confessionals jointly governing. The parties PvdA, KVP, ARP, and CHU remained virtually unchanged during this time.

In 1946, the communist CPN had seven seats, but by 1958 they only had one seat. On the other hand, the liberal VVD’s seats grew from four in 1946 to eleven in 1958. The PvdA, however, remained the largest party after the war, with fourteen seats in both 1946 and 1949, sixteen seats in 1953, and fifteen seats in the council in 1958. Given the challenges of post-war reconstruction, it was important to have a broad as possible municipal executive. One of the aldermen responsible for reconstruction and urban development was ir. L.J.M. Feber (1885-1964) of the Catholic People’s Party (KVP). He had been an alderman before the war and continued in that role from 1945 to 1955. Feber was known for his skill and energy, being a practical building engineer. According to Van der Sluijs (1989), he was someone who never read his documents when he entered the council chamber.

The social-democratic and confessional city administrators were confident that with Feber, the urban reconstruction and extension was in good hands. This Dutch variant of the neighborhood unit could, therefore, count on a large majority in the council.

According to Aardoom (2007) in The Hague, the neighborhoods unit (De Wijkgedachte) was explicitly mentioned in council documents for the first time during the discussion of the budget on 16 and 17 March 1948. The Plan 2000, however, followed Clarence Perry’s idea of the neighborhood unit (1929, 1939) and consisted of neighborhoods with a population between 10,000 and 20,000 people, which were further divided into smaller neighborhoods with around 1,000 inhabitants. Perry envisioned the neighborhood unit as a low-traffic village with social amenities located at its center, housing a population of 6,000 to 10,000 individuals. Access roads would run around the neighborhood, connecting different villages or neighborhoods.

The city thus became a succession of neighborhoods or villages. Perry wanted to use the idea of the neighborhood unit to put a stop to the social fragmentation and massification of housing. The neighborhood unit should bring security and stimulate a rich community life. A person should be able to live in the same neighborhood unit all their life. With the principles of the neighborhood unit that Perry offered, the makeable society found a willing ear among many administrators in the battered post-war Netherlands.