Cityscape of laissez-fair 1860-1890

The development of Residential parks, civic quarters and working-class neighborhoods

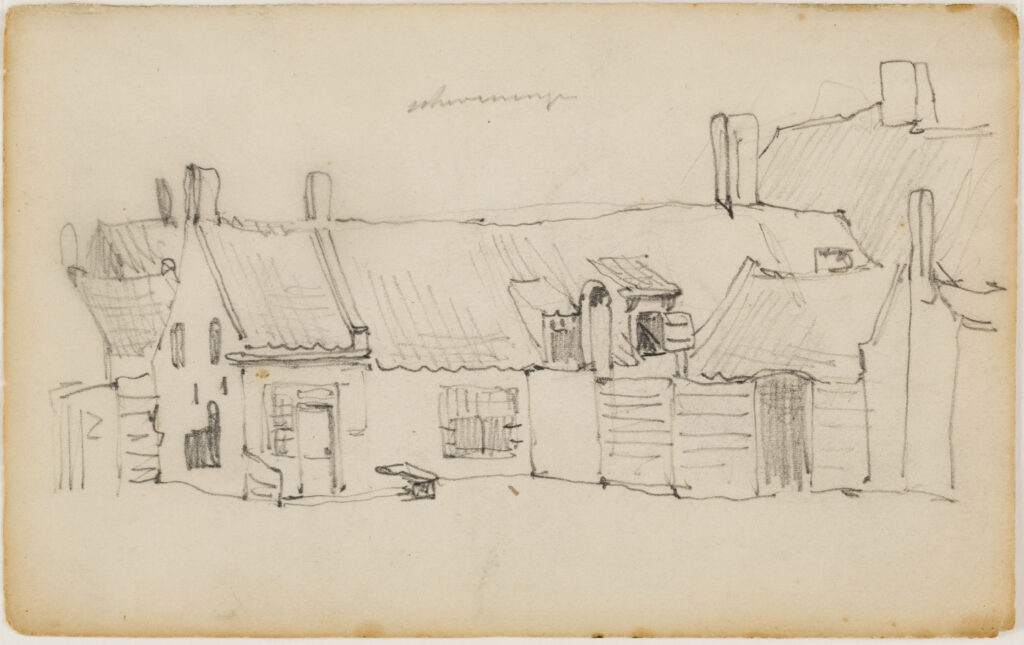

How the village character took shape into the new suburbs uw header hier toe

The city image of the beautiful city was not always a frivolous city image. The residential parks were given beautiful villas in leafy greenery. The bourgeois districts were uniform rowhouses in eclecticism architecture whit a lot of plaster on brick. In the working-classdistricts, the masonry was dull and the meagre frivolity of the bourgeois neighborhoods disappeared. Because of the way of layout of neighborhoods and construction of houses, the three ensembles each got their own character and location within the municipality. Asargued in the chapter above, the village character was not a conscious choice for a city image, rather it was the result of geomorphology and geopolitical context.

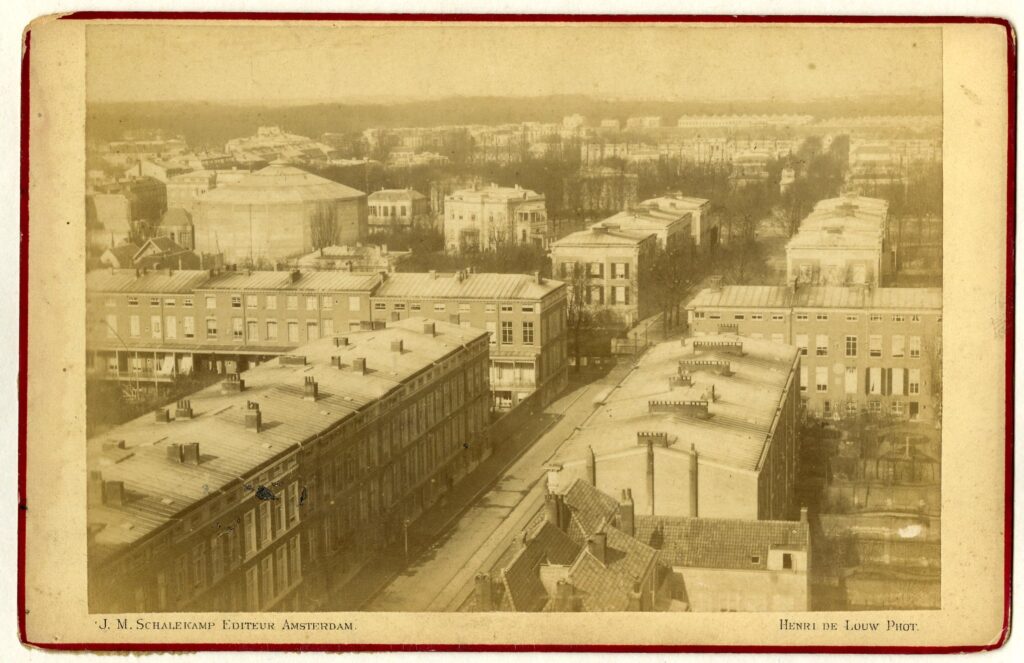

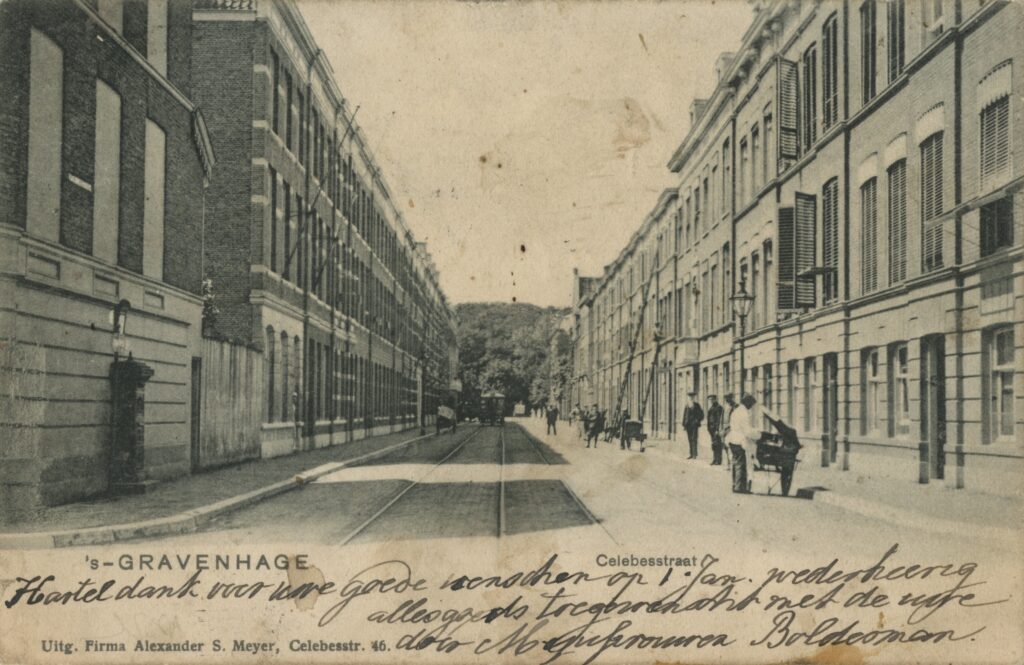

A vivid picture of the old city and the new neighborhoods was sketched in literature by the journalist Johan Gram (1893, 1906), the writer Louis Couperus, the resident Nini Brunt (1977) about the old city and at the time new Zeeheldenkwartier, the city walker Ton Ven (1962)which is a pseudonym for the writer Bordewijk whose stories often take place in The Hague. Supplemented with the first photography, this gives an impression of the atmosphere and character of the sometimes completely different districts of The Hague.

After the French Era, the Hofkwartier and the village of The Hague were legally united and gained one municipal administration. In the year 1861 a breakthrough of great significance took place. The medieval village ‘die Haghe’ with its center the Dagelijkse Groenmarkt (daily green market) was connected to the Buitenhof by the construction of the Gravenstraat. The symbolic wall between the court and the bourgeoisie was torn down after 600 years.

However, between 1841 and 1892 new walls had been erected with the Stedelijk Keur (urban hallmark) between the wealthy bourgeoisie who lived on the sand in leafy residential parks, the ordinary bourgeoisie on the distinguished streets with double rows of trees and green squares, and the proletariat who kept themselves alive in the bare slums in thepeat. In a relatively short time, the city was spatially divided into three types of urban ensembles where socio-economically like-minded people came to live together: workers’ quarters, civilian quarters and residential parks.

Different socio-economic networks of people coincided with the different qualities of the urban ensembles and facilities. This affected the residential patterns in the city where mostpeople had no free choice (Gram, 1893, 1906) (Eberstadt, 1914) (Van Gelder, 1937) (Bakker Schut, 1939) (Gemeente ’s-Gravenhage, 1948) (Dirkzwager, 1979) (Stokvis, 1987) (Koopmans 1994, 2005) (Schmal, 1995) (Furnée, 2012).

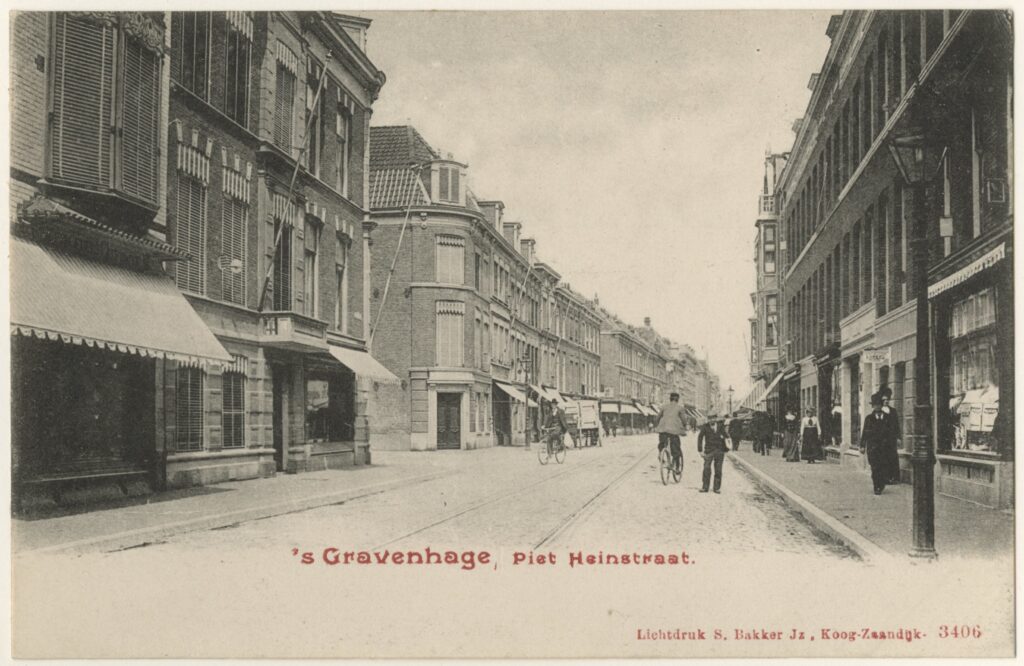

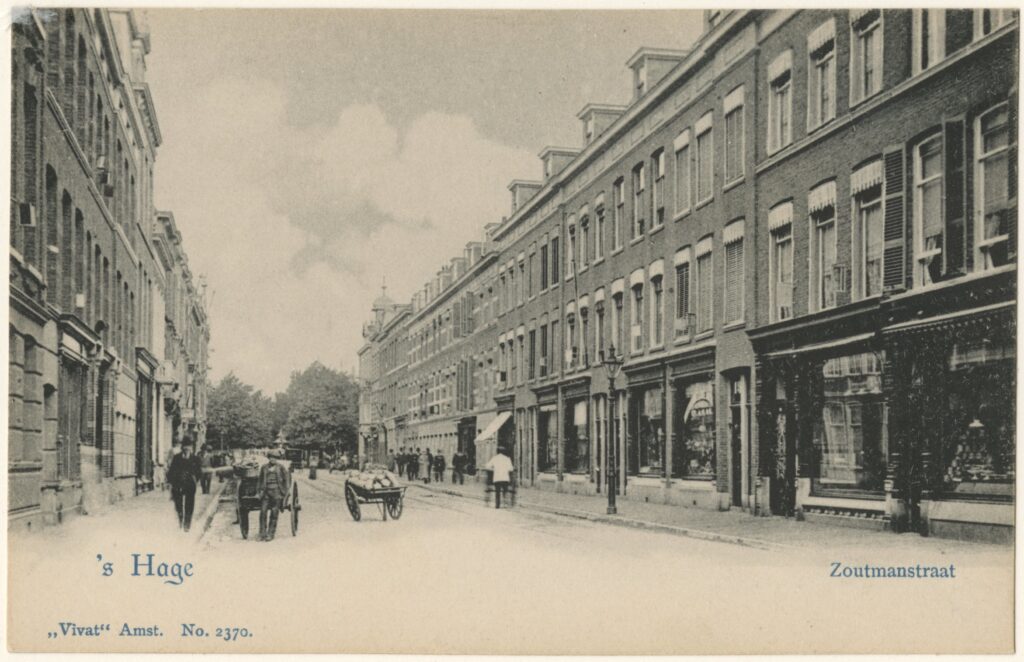

The exodus from the old residential city begins after 1870 and the sorting of the population into residential areas with a different statusand appearance was similar to the developments that were going on in metropolises such as London, Paris and Vienna (Olsen, 1986).Only the building forms were not comparable. While in metropolises and also smaller cities huge urban residential blocks with apartments were built, in The Hague it remained with fine-grained buildings of row houses or at most in two apartments split row house, giving The Hague, together with wide green access roads with double rows of trees, a village character.

The Hague would become more like English than most continental cities in terms of its buildings. In England but also in the Netherlands, Belgium and Bremen, the housing unit is usually the construction unit (although the houses were often constructed in a row of a few houses at the same time) while on the mainland the building unit is often a large residential building or an urban block divided into several housing units (Olsen, 1986: 125). In terms of the socio-economic structure of its population, The Hague was more like London than Paris and Vienna. Because in Paris and Vienna all classes lived together in the large residential buildings, there was a kind of mixture of population. The poorest lived in the attic and the distinguished citizens on the first floor. Because The Hague did not knowthese large residential buildings, the spatial segregation was greater. Houses of the same kind were grouped together in neighborhoods. In addition, the societies with the related networks played an important role and perpetuated the segregated society, just like the clubs inLondon (Olsen, 1986) (Furnée, 2012). Grand cafés such as in Paris and Vienna, where a worker could drink his coffee next to a civil servant, were unthinkable in The Hague. One was aware of the privileged status one possessed. Councilor Stam argued in 1865 in the city council about the appearance:

The Hague ‘is a palatial residence, a city of opulence. I am delighted so often when I hear her praised as one of the fairest citiesin Europe, when I see that wealthy people are constantly attracted by her beauty and settle here to consume their rich incomeamong us. From the influx of such people the city derives chiefly its progress and prosperity. But that progress and prosperity canonly be perpetuated if the city maintains its fame of beauty, which it will only do then, if it is ensured that every enlargement andexpansion is for the least equaled by the beautiful thing we already possess, or, rather, increases its luster even more.’ (Stokvis, 1987: 45).

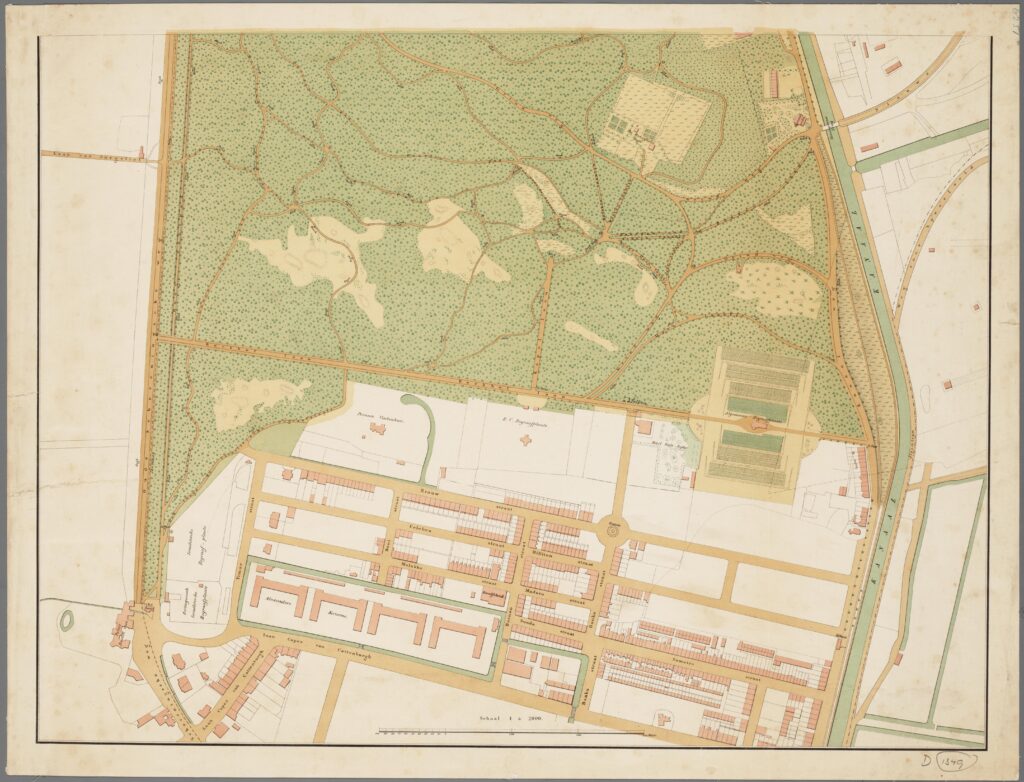

The Hague also differed from other Dutch cities in this respect, there they made an effort to shape the layout of the new city. Rotterdam had Plan tot Aanleg van Nieuwe Straten in de Polders Cool en Rubroek by W.N. Rose in 1858, Amsterdam had Plan tot Uitbreiding van Amsterdam by J.G. van Niftrik in 1866 and Plan tot Uitbreiding van Amsterdam by J. Kalff in 1875. In The Hague one would never get that far. The city was parceled out and built up by building-land-companies (who turned raw land tot ready to build lots) and construction companies (who bought the lots, construct the houses and sell these) in which wealthy citizens bought or resold shares ‘freely in theirname’, invested and made large profits.

The Hague also differed in terms of the expected residential patterns in cities. For these patterns in the pre-industrial city, Sjoberg (1961) presented a model in which the elite of the city lived in the center and the poor were located more to the outskirts of the city. Itwas there that the distance of the poor from the political and religious center was greatest. For Amsterdam, this model is only partiallyvalid (Lesger, Leeuwen & Vissers, 2013). The poor did indeed live on the outskirts, but the rich citizens did not live in the center around 1830, but in an exclusive zone in the canal belt. Cadastral data on real estate from 1832 were used as the source for this study, whichwere translated into rents. For The Hague, too, the model only partially holds Sjoberg’s conclusion. After all, legally the Hofkwartier, which covered about 25% of the city, was a separate zone until the beginning of the nineteenth century. The Lange Voorhout, the Vijverberg and the Plein formed a green universe of wealthy citizens and administrators far from the noisy center at the DagelijkseGroenmarkt, the Hoogstraat and the Wagenstraat. On the outskirts of the city, you could indeed see the shabby houses as in the Rivierenbuurt, Het Kortenbos and Spuikwartier (Stokvis, 1987).

In The Hague, the canals were only built at the beginning of the seventeenth century, which is fairly late. The advantage was that the surface area within the canals was much larger than in classic Dutch water cities. There was simply more room to grow and the canalswas not a barrier. Until 1870, apart from the spacious country estates, the urban developments also took place mainly within the canalsas densification in inner areas and on the edges or as damage repair from the French Era. When in The Hague after 1870 the layout of neighborhoods outside the canals was finally taken up by private individuals, handy entrepreneurs anticipated the social economical differences in the city. Due to the enormous influx of population, homes were built in stock, whereby an estimate was made of the budget of the buyers or tenants. Building-land-companies, construction companies and architects shaped segregation with painful precision with houses, streets and urban ensembles. In all three ensembles, the village character was emphasized by the low buildingsand small scale. No Paris, Copenhagen or Berlin. Although the qualities between the low-rise buildings of the residential parks andslums differed.

Three urban ensembles

Between 1870 and 1890, the three types of urban ensembles were sharply defined in terms of typo-morphological structure.

In the working-class districts such as the Schilderswijk, meadow after meadow was filled with building blocks, with slums in the courtyards,most of which were demolished after the war. Much better in quality, but sometimes with a similar building structure, some were charity courtyards.

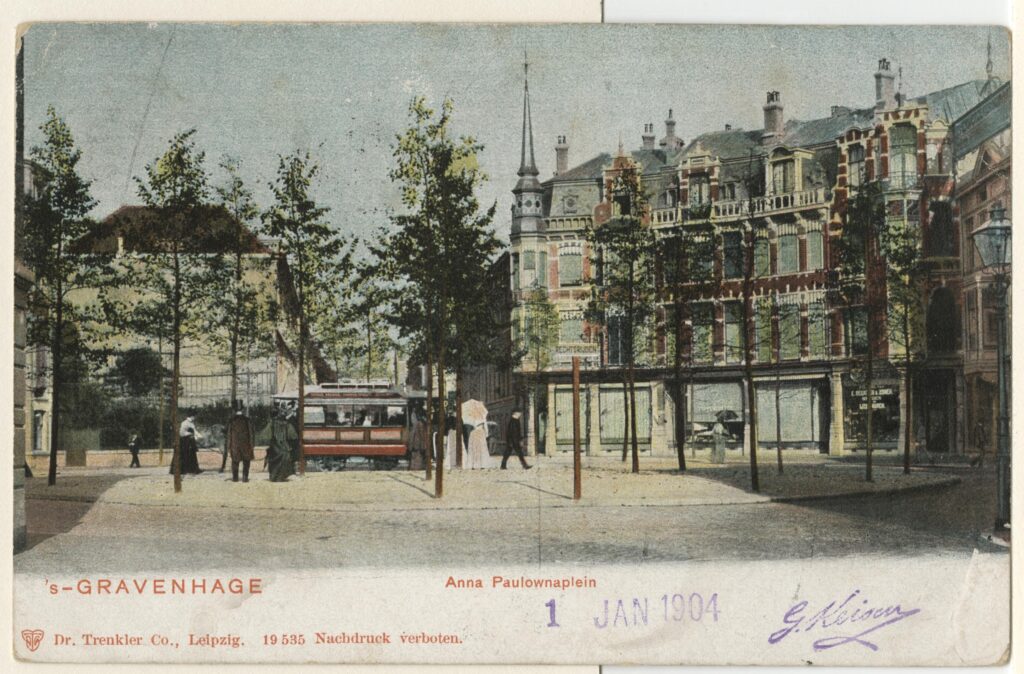

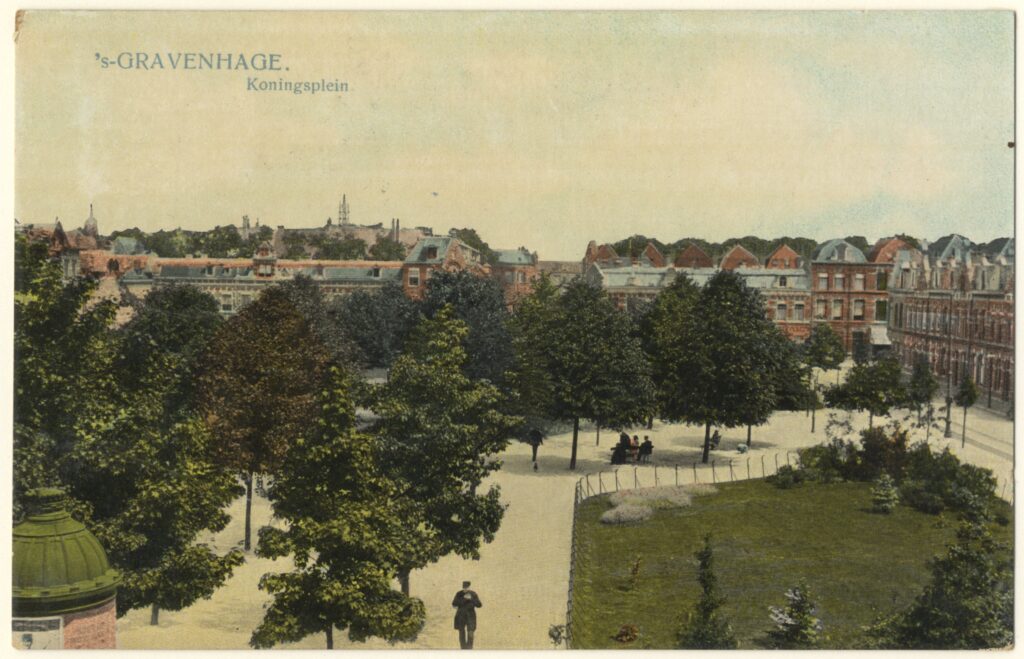

The civilian districts such as the Archipelbuurt and the Zeeheldenkwartier formed unique iconic urban ensembles with spaces consisting of grid street plan with representative wider streets and ronds-points such as Bankaplein, Anna Pauwlonaplein, Prins Hendrikplein and Koningsplein. The other streets were smaller and sometimes courtyards appeared in the courtyards.

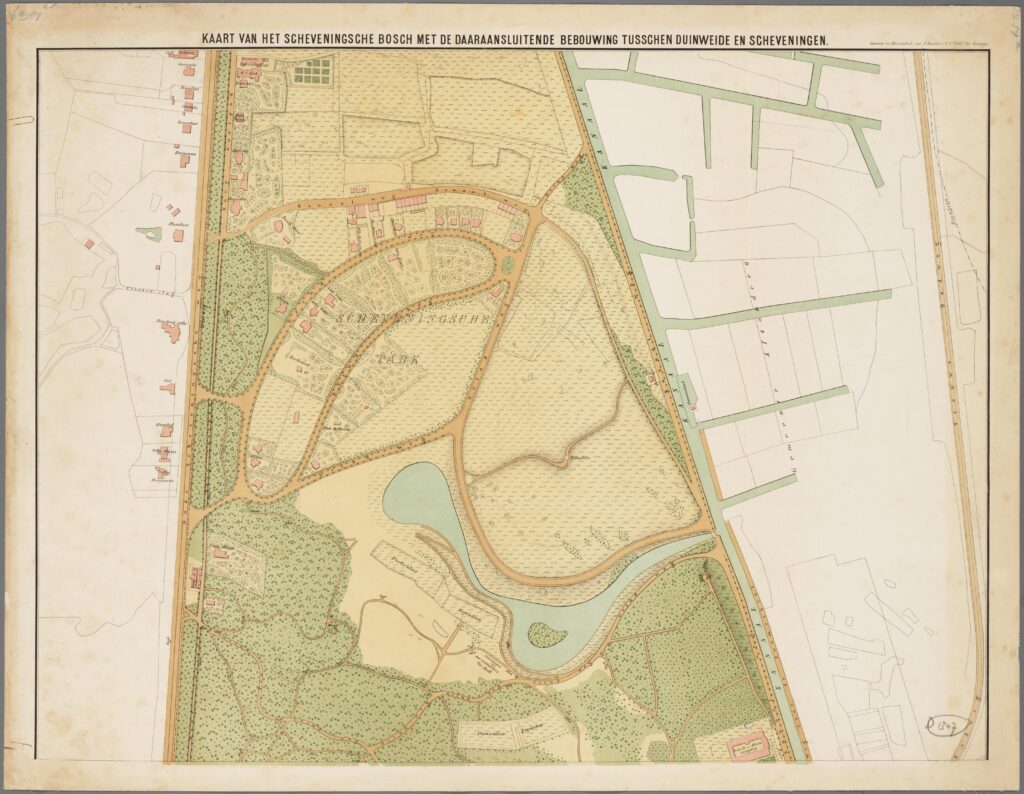

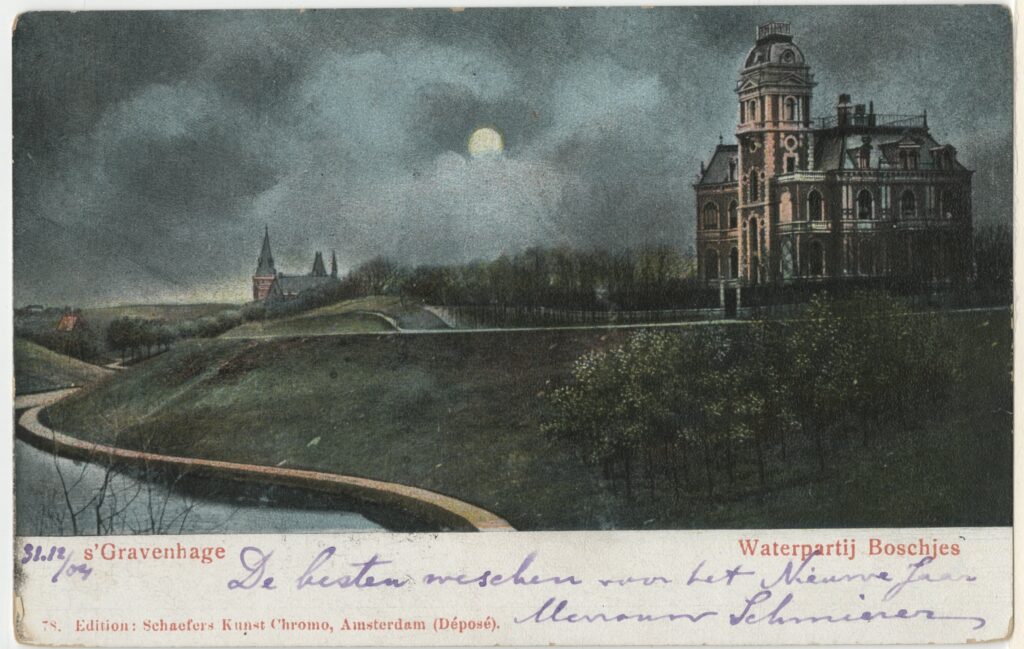

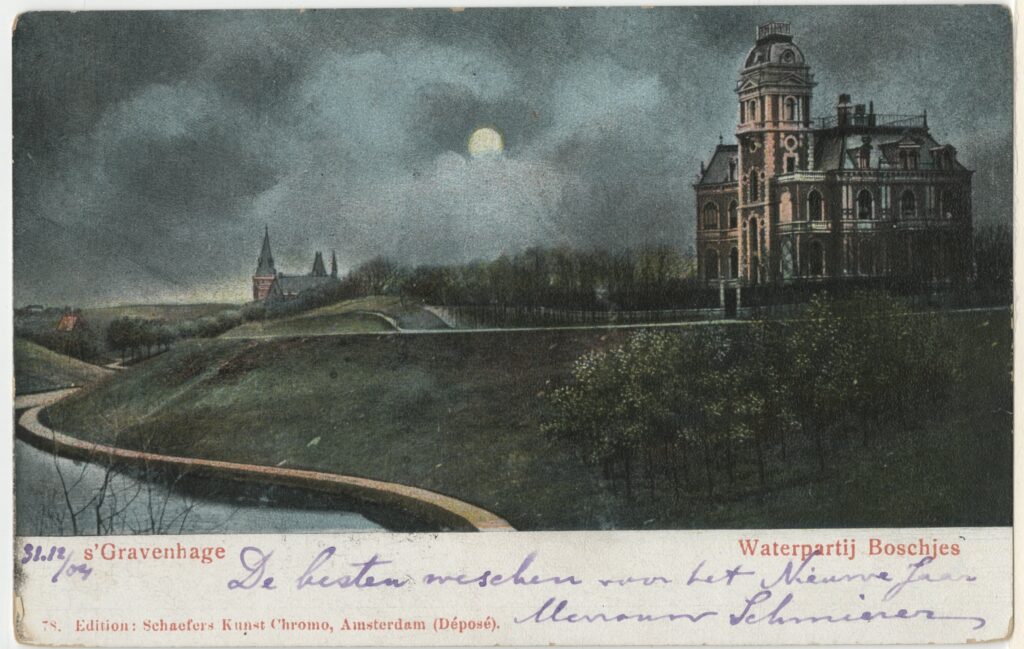

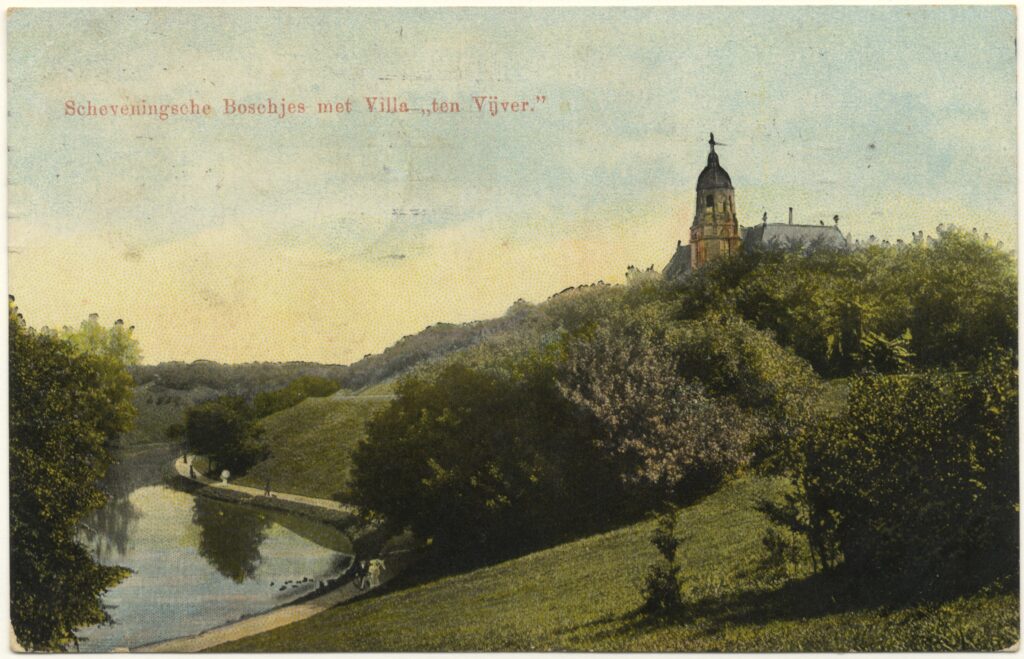

The residential parks were located in a ring around the Scheveningse Bosjes in the vicinity of the seaside resort, such as the Van Stolkpark and theBelgisch Park. In a park-like setting stood the white villas with verandas and balconies, the summer houses of port barons and industrialists.

The social homogeneity within the living environments became an increasingly important consideration when choosing a place to live (Stokvis, 1987) (Schmal, 1995). Driven by status or lack of money, socio-economically like-minded people sought each other out in the qualitatively different neighborhoods. The wealthy in the residential parks, the citizens and in the civic quarters and the paupers in the revolution-building districts. Each district was given its own atmosphere, its own amenities, its own urban spaces and its own typology ofbuildings. The leafy greenery was mainly reserved for the residential parks and the avenues through civilian districts such as Regentesselaan.

The activities of the lawyer and entrepreneur Mr. Th. van Stolk were exemplary for the period 1860-90. On the sand in a park-like landscape, he laid out the Van Stolkpark with its beautiful white villas by, among others, the architect Westra. In the Zeeheldenkwartier, Van Stolk’s street plan was already more sober and simple houses for the lower middle-class were built. In the Rivierenbuurt workers’ quarter, Van Stolk developed workers’ houses and slums of the lowest quality. The trade-off between the investment costs and therevenues was assessed differently by Van Stolk at each location in the city.

A factor in this must have been that the original land price negotiated by the Grand Duchess at the auction near the seaside resort wasprobably different from elsewhere in the city. The motive of all the individuals who worked on the city and organized themselves intoLimited Companies was usually the same: maximizing revenues.

Causes of spatial segregation

There were a number of important factors that led to these three specific urban ensembles.

First of all, the state formation process had entered a phase in which wealthy citizens participated more than before in municipal government thanks to the Constitution (1848), Municipal Act (1851) and the census suffrage that was introduced in 1848 until the amendment of the law in 1887, after which the middle-class was also allowed to vote. The main people involved in the city image of laissez-faire were these wealthy citizens. Just after the introduction of the municipal act, the conservatives still dominated in The Hague, but the liberals gained more and more ground until they gained the majority at the end of the nineteenth century. The era of Mercantilism, the ossified market, protectionism and conservative guilds came to an end and liberalization of the economy and free trade in the colonies increased. Until 1850, the Netherlands was more or less at a standstill, but between 1850 and 1890 the industrial revolution would continue. This liberal state was a prerequisite for industrialization (Lintsen et al., 1992-1994, 2003, 2005).

Secondly, the Crédit Mobilier phenomenon suddenly made a lot of international capital available (Vos, 2003). In Public LimitedCompanies, various (construction) disciplines could be organized and undertake urban development together. The shares of thesecompanies were not traded in registered form. Public limited companies already existed in the seventeenth century, but due to changesin the capital market, a new dynamic took place: many more entrepreneurs took a gamble, conservative and liberal.

Thirdly, there was a significant increase in population and the city received many new affluent residents. There was a densification withinthe canals and courtyards were filled up at a rapid pace. The quality of life became unsustainable and the middle-class from the city center moved to the new civilian districts. With this population increase, Crédit Mobilier and Public Limited Companies made it possibleto build for the anonymous housing market. In addition, potential buyers or tenants were already anticipated and the differences between the neighborhoods were exaggerated by the entrepreneurs. These national and international developments were reinforced atthe local level in The Hague by the specific population structure with a broad upper-class in the city and because a lot of building landwas publicly auctioned from the estate of Willem II.

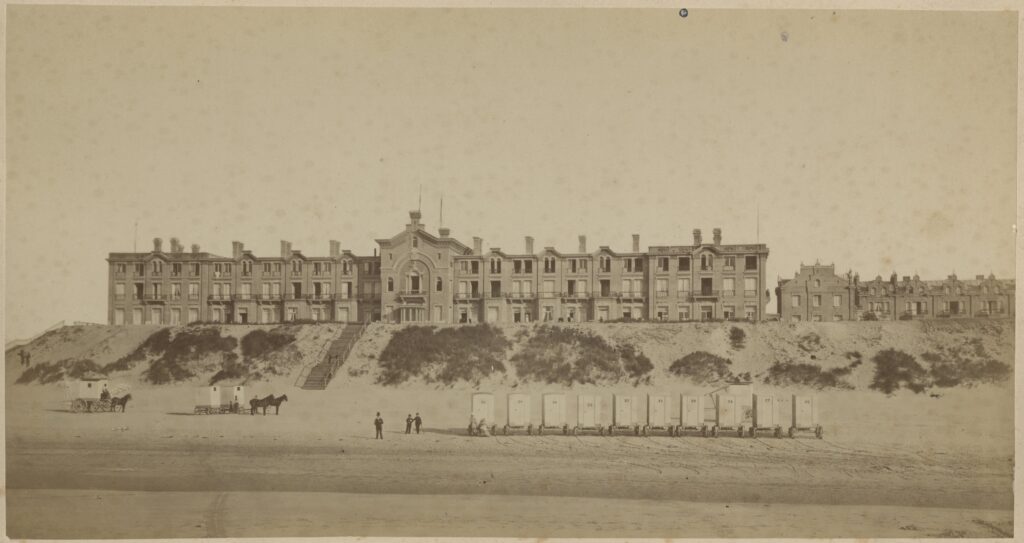

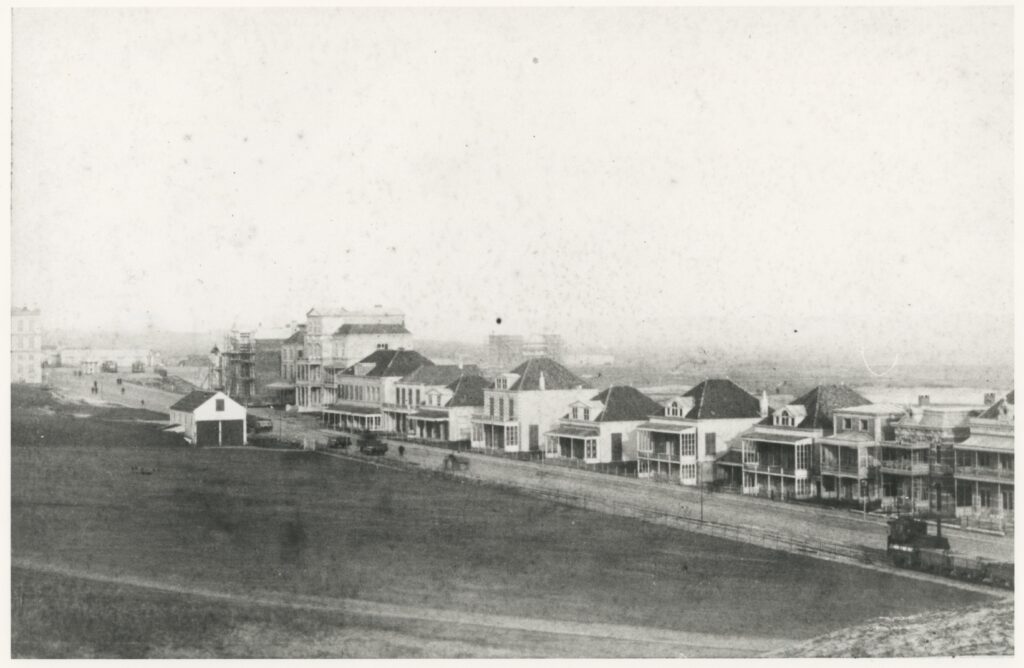

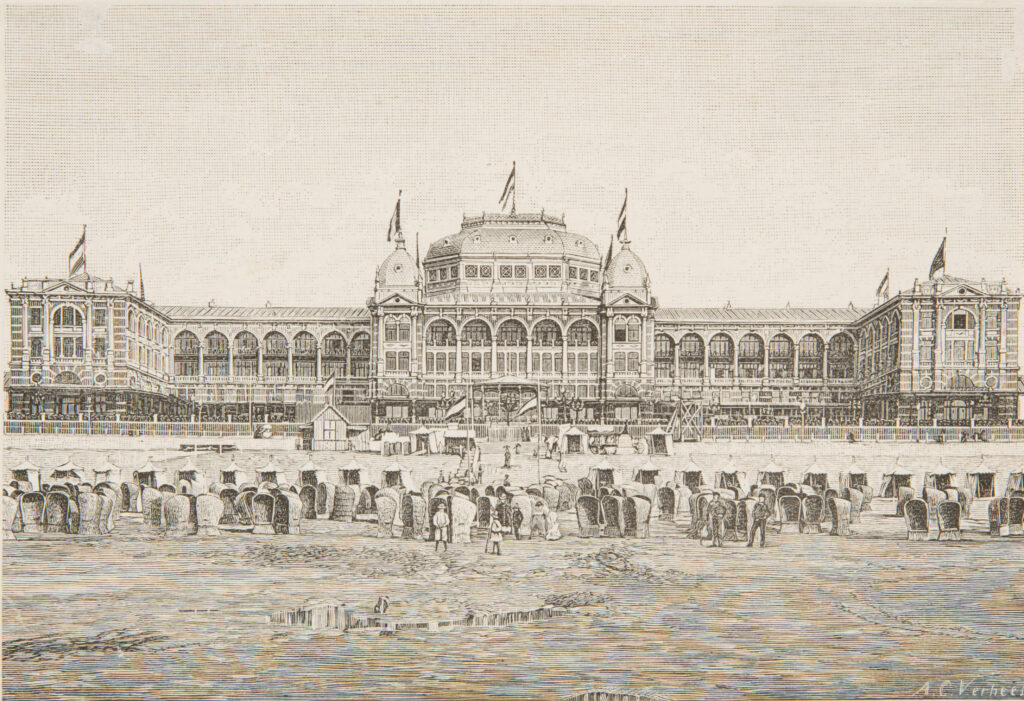

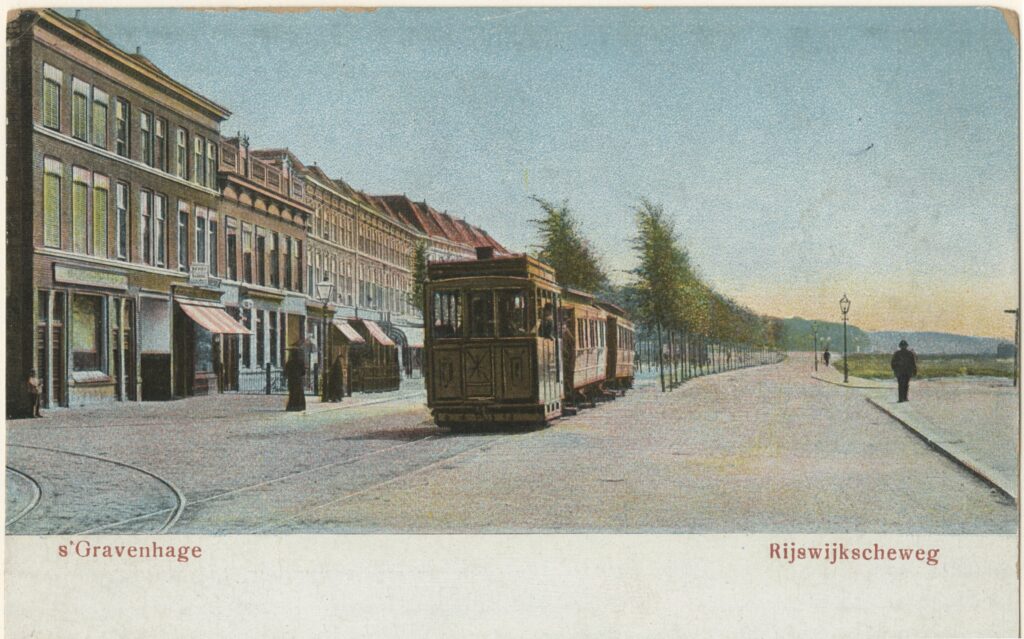

Fourth, the available land around The Hague offered space for the new districts. As early as 1876, the Grand Duchess began selling outer parts of Willem II’s vast estate to building-land-companies. This concerned approximately 265 ha of the total 600 ha of contiguouse states: Sorghvliet, Buitenrust, Rustenburg, Hanenburg, Houtrust and Segbroekpolder. At the time of the sale, the Sorghvliet park withthe Catshuis was still excluded (Goekoop, 1953). In the years that followed, pieces of land were always auctioned. Furthermore, the seaside resort attracted many financiers from Paris, Amsterdam and Antwerp. Partly because the casino was no longer an elitist closed club, but attracted the general public with the gambling game. The old municipal Kurhaus was sold to Maatschappij ZeebadScheveningen MZS and replaced between 1885 and 1887. The construction of the steam tram routes (Stadtbahn) between 1878-1887 along the outskirts of the city brought visitors to the seaside resort and Kurhaus. By the same financiers who had previously invested money in the MZS and the railways (Crefcoeur, 2010).

Fifthly, the disastrous Het Stedelijk Keur that divided the city between 1841 and 1892 into a zone with the strictest rules for the beautifulfaçade on the streets and squares, and the free hand and the lack of laws and regulations for buildings that were not on streets such asin courtyards and meadows. The beautiful facades were built on the wide streets and squares with the fragrant lime trees had crevicesthat led to miserable exploitation slums in the courtyards where one of the darkest episodes of The Hague’s social history took place. This Het Stedelijk Keur suggests a convenient political compromise between conservatives who stood for a city with beautiful facadeson the streets and liberals who were mainly in favor of government abstinence in courtyards and meadows. Especially between 1840 and 1870 there would be a considerable densification within the canals with major consequences. Article 41 of Het Stedelijk Keur (TheUrban Label) read:

‘No one shall be permitted to erect a new building on the street or the public road in connection with adjacent buildings, streets orsquares, other than the Mayor and Aldermen shall judge it useful on presentation of a notice or declaration of the building, on painthat it shall be demolished again at his expense.’ (Baker Schut, 1939: 6).

So only permission was needed from the municipality for building along streets and on squares. For Bakker Schut, this article was mostlikely the cause of the questionable way in which housing conditions in The Hague would develop in the years that followed: the slums in the courtyards and meadows, the years of the laissez fair and free enterprise (Bakker Schut, 1939: 6). In The Hague, Het Stedelijk Keur laid the foundation for the city of living on the sand and living in the peat. From the city of the well-to-do and prosperous bourgeoisie who live on the beautiful squares and streets and the paupers in the courtyards, far out of sight.

These causes led, specifically for The Hague the last two, to the way of layout The Hague’s neighborhoods until about 1890. On the one hand, there were the Hague hygienists such as doctor Schick and engineers who denounced the lagging behind of utilities such asdrinking water and sewers, and a lack of building legislation, especially in the slums. On the other hand, there were the architects and journalists who denounced the dullness of the new neighborhoods and many in the city felt that there was a lack of national historical awareness, after all, history was what united the population and brought a sense of community. The call for quality was loud until the national amendment of the law in 1887 also allowed the ordinary bourgeoisie to vote and in the following period the unbridled laissezfaire came to an end.

Census suffrage 1848-1887 and the wealthy bourgeoisie

Partly determining the segregation of urban ensembles was the influence and voice that wealthy citizens gained in the city government, caused by the change in the polity and the liberalization of the economy under Thorbecke and by the arrival of the Constitution in 1848 and the Municipal Act in 1851.

The census suffrage that would exist from 1848 to 1917 received a major change in 1887, after which the ordinary bourgeoisie also received a vote in the municipality. Only citizens who contributed more tax than they received (in the form ofwages or benefits) were allowed to decide on the use of taxpayers’ money, was the idea behind census suffrage. Wealthy votersdominated local politics between 1848 and 1887, shaping the division of living in the bog land and on the sand.

With the introduction of the Municipalities Act in 1851, the highest governing body of the municipality consisted of the elected council and a board of one mayor, appointed by the Crown, and several aldermen who emerged from the council.

From 1851 to 1919 this meant the dominance of two parties in The Hague. The conservatives in the early years, who mainly stood up for the interests of the well-to-do bourgeoisie, nobilityand regents, and later especially the liberals, who were concerned about the free enterprise and limitation of influence of themunicipality (Stokvis, 1987) (Schmal, 1995). The social historian Stokvis argued about the different approaches:

‘Conservative’ councilors who defended the living pleasure of genteel citizens and ‘liberal’ councilors who shared the position of building contractors with arguments from economic theory only differed on the role of the government in urban sprawl. While courtyard houses were built for workers on private indoor land in the city center, after 1860 villas were built for well-to-do citizens on public streets outside the canals. Affluent inner-city residents and newcomers settled in the suburbs, which initially led the council to strictly monitor their construction in order to ensure an attractive living environment for taxpayers.’ (Stokvis, 1987: 45).

Between 1851 and 1887, the city board was in the hands of privileged citizens and the city council was constantly weighing and weighing the urban facilities and amenities. Still, there was a tension. On the one hand, the tax paid by the bourgeoisie called for public hygiene, public amenities and representativeness of the city, but on the other hand, they also demanded that the municipal tax be keptas low as possible. It wasn’t until the constitutional revision of 1887 that the interests were placed entirely differently in the city counciland the city.

From now on, men who owned or tenanted a house with a rental value above a certain minimum could also vote. Article 80stated that, among other things: Dutch male residents aged 23 years and older who pay a certain minimum sum in direct taxes, or whoare owners or tenants of a house with a rental value above a certain minimum (elaboration: over the last expired year of service withregard to the occupancy of a house fully in the personal tax or for at least 10 Dutch gulden in the land tax and have paid tax bills). From that moment on, amenities such as utilities and infrastructure were built in Dutch cities at a rapid pace.

The new upper-class

Between 1830 and 1940, the population of The Hague and Rotterdam grew more than twice as fast as that of Amsterdam and theNetherlands (Gemeente ‘s-Gravenhage, 1948), This growth is explained by the fact that Rotterdam and The Hague benefited muchmore from the strong economic growth and industrialization that took place in German cities after the unification of Germany in 1871(Ladd, 1990). Amsterdam and Rotterdam were already cities of size, The Hague was catching up. Compared to 1830, the population ofAmsterdam had quadrupled in 1940, while Rotterdam had eight-and-a-half times the number of inhabitants and The Hague even ninetimes. In 1849 The Hague had 72,225 inhabitants. The number of inhabitants grew to 90,277 in 1869, making The Hague the highestnumber of residents ever. In 1889 the city had 156,809 inhabitants, an increase of more than 200% compared to the year 1849(Gemeente ’s-Gravenhage, 1948: 47). According to the Staats Courant, between 1859 and 1889 the number of wealthy and eligiblecitizens in The Hague (87%) increased much faster than in Rotterdam (14%) and Amsterdam (6%) (Schmal, 1995). Between 1850 and1870 the city would still densify within the canals, after which the city would grow outwards with new residential areas.

From 1870 onwards, the exodus of wealthy citizens from the city center started to the new hygienic residential areas such as the Zeeheldenkwartier outside the canals. The city underwent a transformation from a residential work city to a service city, from a darksmelly water city to a hygienic and illuminated city with shops and offices, but also with the decay of certain residential neighborhoods inthe old city. This change was accompanied by an increase in land costs in the attractive parts of the city, which accelerated that process(Bakker Schut, 1939) (Gemeente ‘s-Gravenhage, 1948) (Stokvis, 1987).

The population growth with wealthy citizens who settled in the residential parks was also reinforced by the special position that TheHague had as an administrative city within the geographical network of Dutch cities. The Hague also offered an attractive livingenvironment with residential parks, luxury warehouses, ‘gymnasia’ and ‘hbs’ (secondary schools of different levels), theatres, seasideresort, beach and societies.

At the turn of the century, the ministries also expanded considerably, so that the share of civil servants in the labor force became increasingly important. There was a large well-to-do civil service, whose influence on the city has hardly been portrayed, but which must certainly have played an important role. The rapid growth of the civilian districts may have something to do with this. Furthermore, more and more embassies and headquarters of companies and trading companies that wanted to stay close to the center of power were established there, especially when after 1870 the trade on the colonies was released by the liberal minister De Waal of Colonies and private individuals were given ownership of Java with the Agrarian Act. Schmal argued that: ‘The growth of The Hague was not accompanied by mass immigration of poor populations. The residence mainly had wealthy newcomers who came to the pleasant living environment that the royal city offered.’ (Schmal, 1995: 187). The well-to-do citizens and civil servants gave The Hague a broad socioeconomic top and a sizeable underclass of caretakers in the domestic service, workers who worked mainly in the care industry and soldiers of the garrison.

In the period between 1859 and 1909, the cities diverged considerably in the occupations of its labor force (Schmal, 1995). The data onthe number of families with one or more servants also showed that there were significant differences between the three major cities. Inthe year 1909 in The Hague 11.7% of the families had a maid and 4% had more servants, in Amsterdam this was only: 7% and 2.1% and in Rotterdam only 6% and 1.8%. But it was mainly the ‘Statistics of Income and Wealth’ that showed the large differences in theassessments of taxes (Schmal, 1995: 198). The new affluent residents had different requirements for facilities, homes and livingenvironment. The need for fashion warehouses and luxury shops, with the latest fashion from Paris, Vienna and Brussels, was great.The proximity of the seaside resort and the beach, the luxurious bathhouse and bazaar on the Zeestraat, the new zoo, panoramas and theatres for stage performances and musical performances offered the new wealthy entertainment. The ‘Sociëteiten’ were the center ofthe social life of many inhabitants of The Hague (Stokvis, 1987).

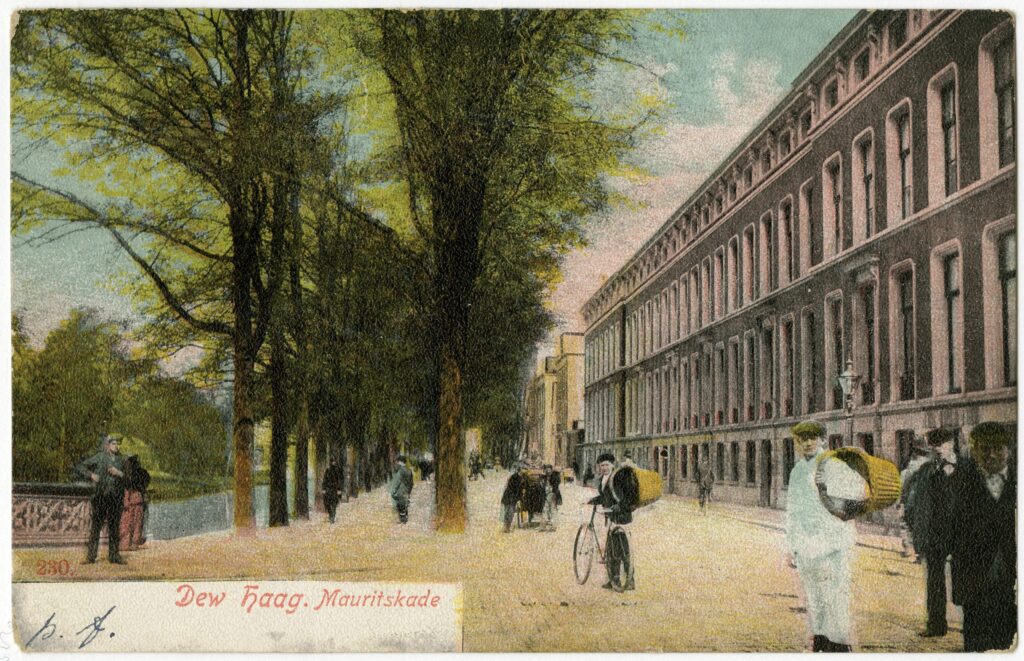

In addition to the differences in facilities and amenities, there were also considerable differences in the type of residential houses withAmsterdam and Rotterdam. In The Hague, mainly large and spacious homes were built for well-to-do citizens and the middle-class.These houses were given a raised first floor with often a beautifully ornamented balcony. Space was reserved for the maid in the atticand at street level in the lower basement with the kitchen: the civilian house as designed by the architect Delia. A house like on the Mauritskade no.43 where the author Louis Couperus was born in 1863.

Capital: crédit mobilier and constructing for the anonymous market

The layout of the first new suburbs and the change in the old city within the canals were accompanied by a new form of financingconstruction activities and therefore of the urban extensions. Because they started producing homes in stock in large quantities, homesfor an anonymous market, entrepreneurs anticipated the type of customer. Was it someone with a well-stocked purse, someone from themiddle-class or were they constructing units for workers?

Obtaining capital for a company was considerably simplified after 1860 when the Crédit Mobilier made a rapid rise in the Netherlandsfrom Paris (Vos, 2003). Large sums of money were invested by new credit banks in private enterprises and urban projects. For exempel,the Comanditiekas in Rotterdam (1861), De Algemeene maatschappij voor Handel en Nijverheid in Amsterdam (1863), De Nederlandsche Crediet en Depositi Bank in Amsterdam (1863), De Rotterdamsche Bank (1863) and De Amsterdamsche Bank (1871).Private individuals organized themselves into Public Limited Companies such as building-land-companies, construction companies and operating companies and gradually gained a significant influence on the development of the city. The role of the municipality wasincreasingly restricted.

Expropriation of real estate for urban development was possible from 1851 but cumbersome, in 1887 the court gained control over it. In1889, a Royal Decree (Koninklijk Besluit) prohibited municipalities from prescribing a mandatory street plan (Stokvis, 1987). Theinfluence of entrepreneurs also increased considerably in the seaside resort with the arrival of the casino around 1884 (Crefcoeur,2010).

The new system of financing came from Paris where the brothers Emile (1800-1875) and Isaac Péreire (1806-1880) with their bank’Société générale de Crédit Mobilier’ had already made numerous investments in railways, infrastructure, insurance companies, gaslighting and newspapers. The idea was to invest directly with large sums of money and participate in one particular industry and nolonger invest a little here and there. The bank thus became mainly a lender that acquired a direct interest in a particular company (Vos, 2003). Many private urban projects, railways, utilities, etc. could be financed in this way. The Crédit Mobilier was also a godsend forhousing construction and urban development in The Hague. With short-term loans one could borrow money at high interest rates fromthe new creditbanks (Bakker Schut, 1939) (Kleinegris & Leferink, 1985) (Stokvis, 1987) (Doorn & Nijs, 2005).

This new way of financing came at a price: the process time played an important role in the construction of houses and urban layout,because entrepreneurs had to pay banks high interest rates over the term of the loan. The interest was deducted from the profits of the companies and therefore there was an urgency to keep the time between taking out the loan and the repayment as short as possible.On the one hand, companies wanted speed in development to limit interest costs, on the other hand, the municipality mainly wantedquality. By slowing down the process, it was able to increase the pressure to make companies more lenient in contributing to urbanfacilities. Furthermore, the municipality required in ’the general conditions for building sites’ that if a company had purchased land fromthe municipality within five years of the purchase, the buildings on these sites had to be occupied. The municipality wanted to preventland speculators from leaving construction sites fallow to drive up the price for colleagues. For many building-land-companies, this wasan obligation that they wanted to avoid, because negotiations with the shrewd engineer and civil servant Lindo and his department couldbe time-consuming (Handelingen van de gemeenteraad 1891, bijlage 16: 3).

The creators of the city

The way of laying out neighborhoods determined what the city would look like. Building for the anonymous market meant that the quality and status of the district had to be determined in advance. The construction of neighborhoods and houses between 1865 and 1902 went as follows. A Limited Company or landowner owned or purchased land. This land was sometimes divided up and placed with different building-land-companies. They produced the street plan with a subdivision in building plots for the buildings. The negotiation process with the municipality was about the costs and quality of the urban facilities and connections of the streets. After the street plan was ready and approved, the lots were sold to construction and operating companies.

However, some building-land-companies sold plots before there was approval from the municipality and so the pressure on the municipality was increased. With short-term credit, the construction company paid for the land purchase, paid for building materials and hired workers. In the event of a bankruptcy of the contractor, it was mainly the subcontractors, workers and suppliers who were not paid. In the nineteenth century, many unskilled workers worked in construction and it often happened that these workers were left destitute in the event of a bankruptcy of a construction company (Gram, 1893, 1906) (Bakker Schut, 1939) (Stokvis, 1987). This practice was the cause of much social misery in the housing and construction sector. The adventurer entrepreneurs have just started a new Limited Company. The money borrowed from the mortgage bank was paid to the contractor in installments. The first term went to the building-land-company and the workers who laid the foundations.

According to Stokvis (1987), in 1911 the municipality of The Hague had a total of 140 contractors and about 1,000 self-builders, occasional contractors: people and companies for whom building was not the main profession. When an entrepreneur had obtained a small capital or could borrow a sum of money at an absurd interest rate, he built another row of houses. Building on credit with a short construction time for the anonymous housing market became common. Anticipatory entrepreneurs who built homes in advance or sold the land for housing pots deliberately exalted the status of a particular neighborhood to lure buyers. These neighborhoods were decorated with ronds-points and more wide streets in the residential area.

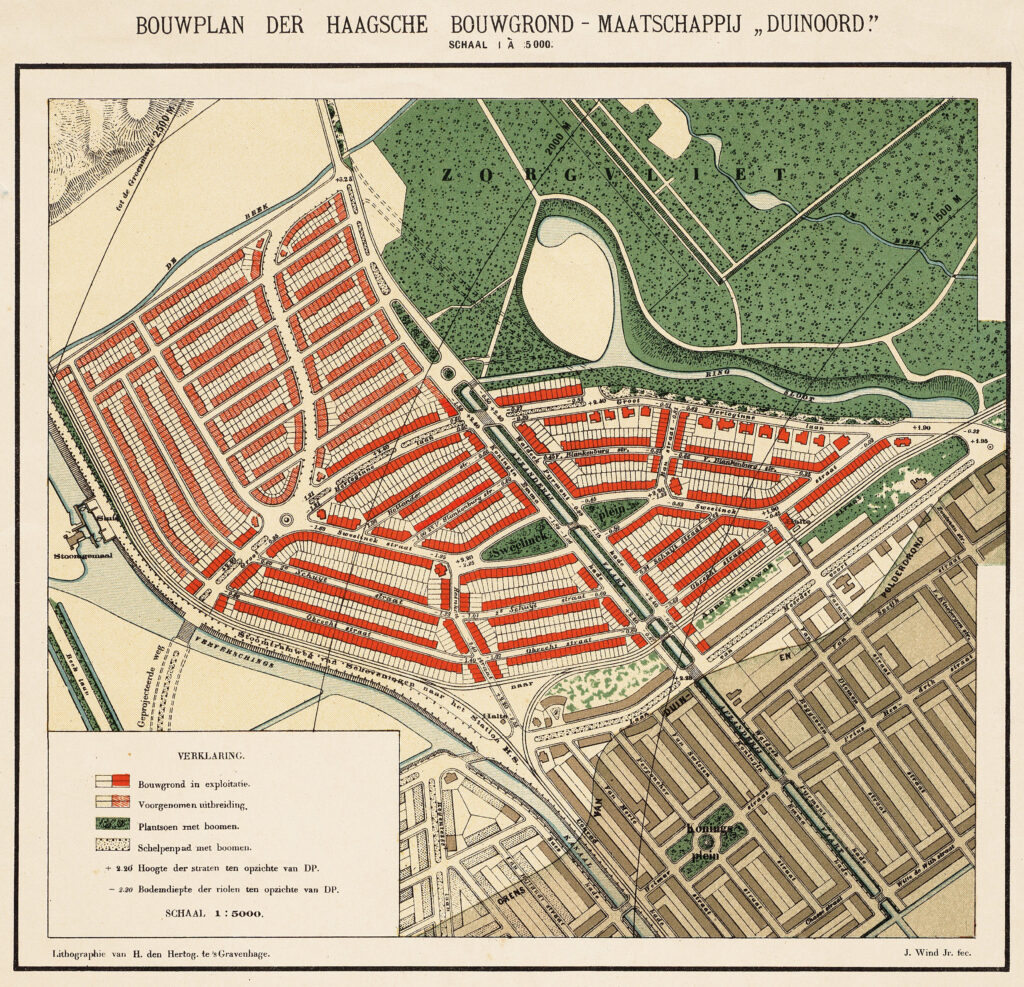

The entrepreneur Scheurleer introduced the idea of living on the sand (dry) and in the bog land with the development of Duinoord. On maps published by his Haagsche Bouwgrondmaatschappij Duinoord the boundary between peat and sand was meticulously indicated to convince residents of the quality of the new Duinoord neighborhood (HGA kl.1119).

The separation between working-class quarters, civilian districts and residential parks was stimulated and reinforced by private entrepreneurs such as Scheurleer. The interdependence of the local government with the owners of the Limited Companies that built the city was great. Especially the council reports with the correspondence between the many Public Limited Companies and the city council between 1870 and 1905 show a shocking picture of the way of urban development.

Limited liability companies came in all shapes and variants such as building-land-companies, construction-companies and operating-companies. Some companies were influential in the city and others did not get beyond one small row of houses. Businessmen with an extensive international network who had enough money to invest were, for example, involved in the development around the Kurhaus and casino, such as Eugène Anselm Jacob Goldschmidt, Louis Guillaume Coblijn and Moritz Anton Reiss (1839-1893) who were partners in the NV Maatschappij Zeebad Scheveningen, founded in 1883 (Crefcoeur 2010). The group around Petrus Josephus de Sonnaville (1830-1925) and assuradeur and municipal councilor for the Liberal Union from 1898 to 1909 Barend Janse Johzn (1847-1916?) also played an important role in numerous iconic urban ensembles, including the seaside resort, the shopping passage at the Buitenhof and residential parks. People who played an important role in the urban development during this period were De Sonnaville, Janse Johzn, Maxwills, Van Stolk and De Lint.

Johannes Antonius de Sonnaville was one of the first councilors and aldermen after 1851. He died in 1860. His son Josephus de Sonnaville initially played an important role in the layout of the Zeeheldenkwartier and the Archipelbuurt between 1870 and 1890. After that, he would focus his activities mainly on the lucrative seaside resort. He was one of the four concessionaires of the Maatschappij Zeebad Scheveningen'(M.Z.S.) and involved in the Société des Galeries, ‘s-Gravenhaagsche Passage-Maatschappij (1876) which had the shopping passage at the Buitenhof built in 1885 by the architect Wesstra. He was also involved in the successor of the M.Z.S. NV Exploitatie Maatschappij Scheveningen (E.M.S.), Exploitatie Maatschappij van Zeerust and NV Maatschappij tot Exploitatie van Hotel Wittebrug.

De Sonnaville, Janse Johzn and Jac. Jenezon, for example, were also commissioners of the Exploitatie Maatschappij van Roerende en Ononroerend Goederen Scheveningen. Janse Johzn was director and supervisor director of Nederlandsche Verzekeringsmaatschappij op het Leven, Nederlandsche Maatschappij voor Electriciteit en Metallurgie and Hollandsche-Belgische Bouwgrond Maatschappij (Belgisch Park).

Janse Johzn was a member of the City Council of The Hague from 1898 to 1909 for the Liberal Union and from 1902 to 1912 of the Provincial Council of South Holland. In 1909, a motion was filed in the Municipal Council of The Hague against Janse Johzn regarding transactions he carried out on behalf of the municipality with the Bouwgrond-Maatschappij-Zandoord (of, among others, Jurriaan Kok, council member and later alderman who had bought land there from Goekoop) for which he would have accepted funds. He resigned from the council for health reasons. With Goldschmidt, Coblijn, Reiss, De Sonnaville and Janse Johzn, international capital gained a face and influence in local politics. Another example is Adrianus Nicolaas de Lint (1838-1894), a material trader from Delft who, like Maxwils, was involved in the development of the Archipelbuurt and the Zeeheldenkwartier.

Neville Davison Goldsmid (1814-1875), for example, showed that urban facilities and amenities were financed on a European scale, whose family was active in London, Paris, Amsterdam and The Hague, in the seaside resort (Lintsen et al., 1993). With the capital of this London and Parisian banking and speculator family, the ‘Compagnie d’ éclairage au Gaz des Pays-Bas’ was founded in The Hague, which had concluded a concession for gas lighting with the municipality for the period 1844-1874, and thereby enforced exclusive rights (Stokvis, 1987). There were major differences between the companies that dealt with the urban development. After the major changes around 1890, Scheurleer and Goekoop in The Hague in particular would be active in the extension of neighborhoods, both with strong ideas about the quality of urban interpretation.

All the companies that dealt with the urban development were Public Limited Liability Companies, a form of legal entity in which the share capital is divided into freely transferable shares. These Limited Liability Companies had the advantage for the partners that there was limited liability for the owners of the shares. For each project (hotels, passages, panoramas, etc.) or urban layout (residential parks, streets, neighborhoods and districts, etc.), a Public Limited Company was established. Hence, most names refer to a location in the city or a particular project. Often several parties worked together in a Limited Company, a kind of construction team in a legal form where each party had one or more shares. The financiers and the landowners often had majority shares (De Sonnaville, Janse Johzn, Goekoop, Scheurleer, Van Stolk), while others, such as architects (Maxwils, Wesstra, Van Liefland), building contractors and material suppliers (De Lint), took a minority share in order to show involvement or to take on the development of a street plan themselves (Maxwils, Van Liefland, De Lint). Everyone shared in the profit and risk of the project.

In addition to the companies that only aimed for short-term profit, there were also those that paid attention to the beautiful city and good facilities and amenities. Delia was already mentioned, but also the engineer and land trader Johannes Bartholomeus Maxwils (1811-1881), who also played a role as a hygienist, and the architect politician Willem Bernardus van Liefland (1857-1919) had a completely different attitude than colleagues such as Vogel, De Vletter and Klomp. Maxwils and probably also the city architect B. Reinders (1875-1890) were relatives of the painter and banker and Hague school painter Hendrik Willen Mesdag (1831-1915) (Groninger Archief, access number: 555 Family Mesdag, 1666-1992). After 1890, Goekoop and Scheurleer also showed that quality was important to attract wealthy buyers to their new neighborhoods. So, there were big differences between the Limited Liability Companies.

If a building-land-company imposed special requirements on the buildings with regard to the image or the construction time, this was done in the land contract with the buyer of the plot. When building-land-companies started with street plans, the municipality also set requirements for these plans. Entrepreneurs then set requirements for the municipality to co-pay for these general facilities or amenities. A situation of negotiation arose between building-land-companies and the municipality about the street plans and amenities of the new neighborhoods, such as with the construction of the Anna Paulowna Park. Initially, building-land-companies donated the land of the public area to the municipality in exchange for the construction of streets, sewers and lighting at municipal expense. However, in the years that followed, the municipality wanted to get rid of these costs and gradually the municipal contributions were reversed. The tension between the building-land-companies and the municipality was therefore constantly present and determined to a large extent the street plans, until the arrival of the Housing Act in 1901. For example, in the dispute between the municipality and Haagsche Bouwgrond Maatschappij Duinoord of entrepreneur Goekoop during the construction of residential parks such as Het Park Zorgvliet (HGA library C k 102 n0. 1-2 from 1902: Het Park Zorgvliet: overprint of the articles concerning this park appeared in newspaper De Avondpost).

Well-known architects such as Van Liefland were involved in many building-land-companies. For example, van Liefland and Simons were involved in the building land company Burgerlijke Maatschappij Bouwlust, which was involved in the slaughterhouse and the cattle market development around 1887 (Simons later became alderman in The Hague) (Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Ministry of Justice: Centraal Archief Vennootschappen). Van Liefland was also involved in the Public Limited Companies such as: De Toekomst, De Maatschappij voor Onroerende Goederen, ‘s-Gravenhaagsche Bouwmaatschappij and Exploitatie Maatschappij Scheveningen, Bouw Maatschappij Anna Paulowna (Handelingen van den Gemeenteraad 1891, appendix 78: 18). It was conceivable that a renowned architect like Van Liefland owned a minority share in all the projects he worked on to show his loyalty and belief in the project. Together with the architect Wesstra, Van Liefland was, for example, in Zuider Bouwgrond Maatschappij in The Hague where they developed the lands of the widow Pronk (Bijvoegsel Nederlandsche Staatscourant, 4 September 1895, no.207: Naamlooze vennootschap: ‘Zuider Bouwgrond-Maatschappij’ in The Hague).

This way of financing, laying out neighborhoods and building houses for the anonymous market with Limited Companies led to the city image of laissez-faire with residential parks in leafy greenery, fashionable civic quarters with a rond-point and working-class neighborhoods full of slums and epidemics.

On June 24, 1832, skipper Knoester’s fishing boat landed in Scheveningen and, in addition to fish, also landed cholera with an estimated 378 deaths in the densely built-up slums of Scheveningen. Meanwhile, another epidemic had also crept into the slums of The Hague and Scheveningen, typhus. With the city filled with working-class neighborhoods and slums, and the poorly fed new citizens, the number of deaths rose rapidly in the working-class neighborhoods (Schick, 1852) (Krul, 1892) (Oorschot, 2021). It was a miracle when a baby stayed alive.

Conflicts about health, hygiene and facilities 1851-1887

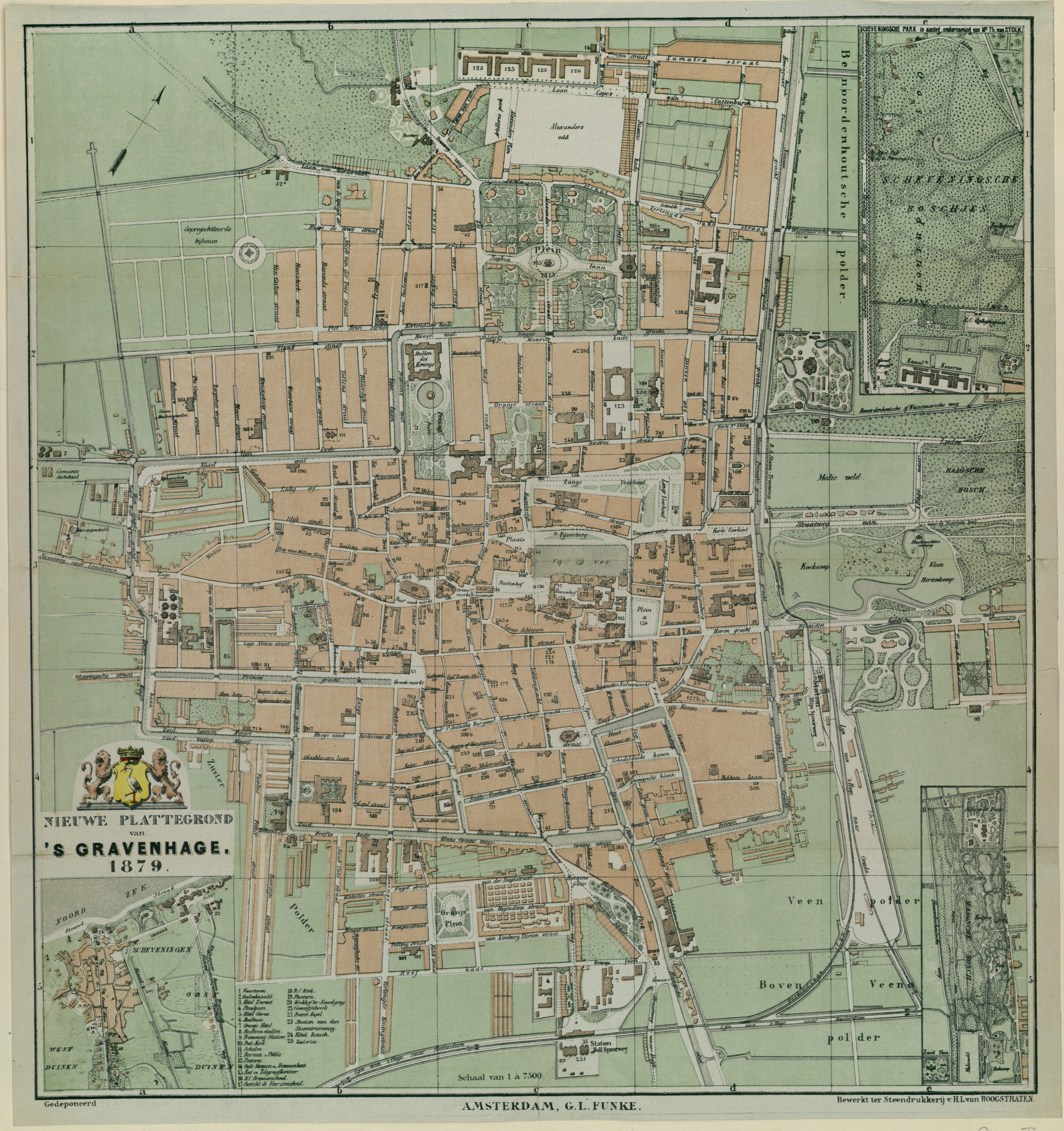

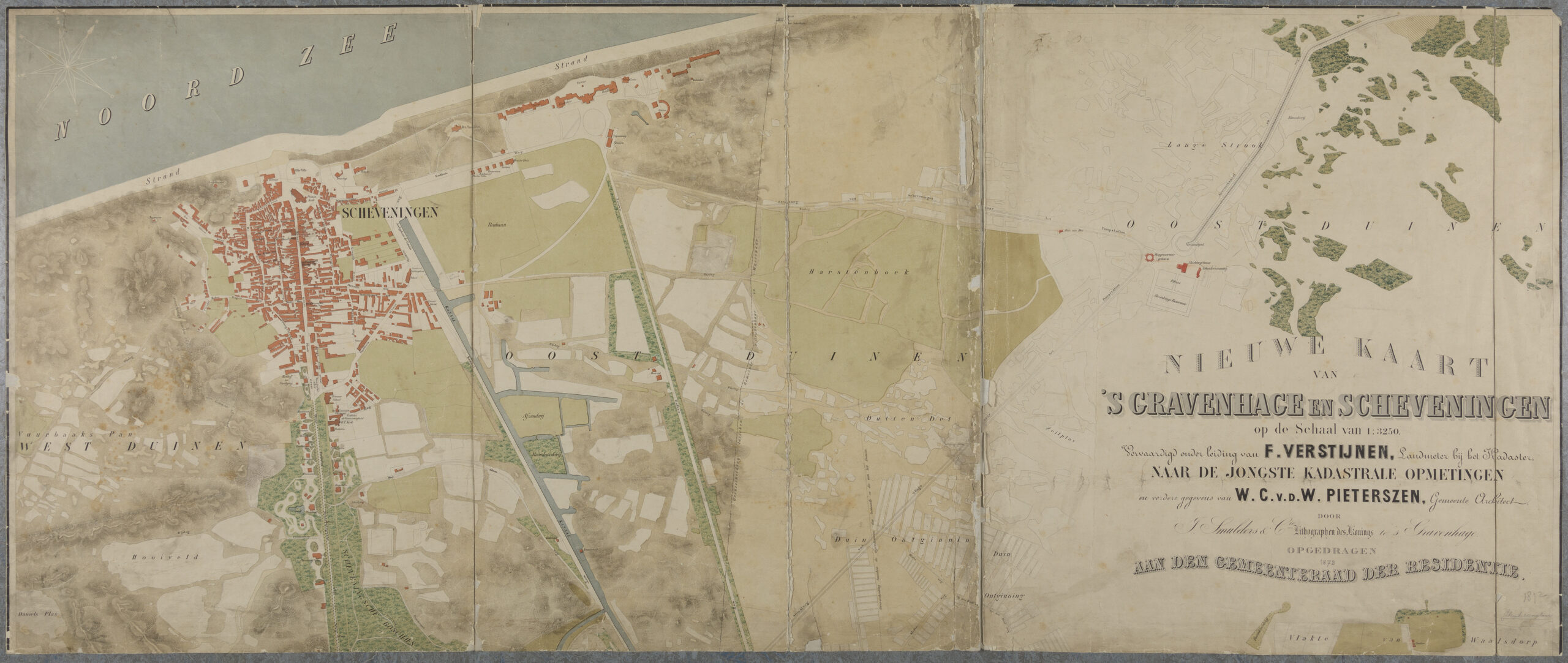

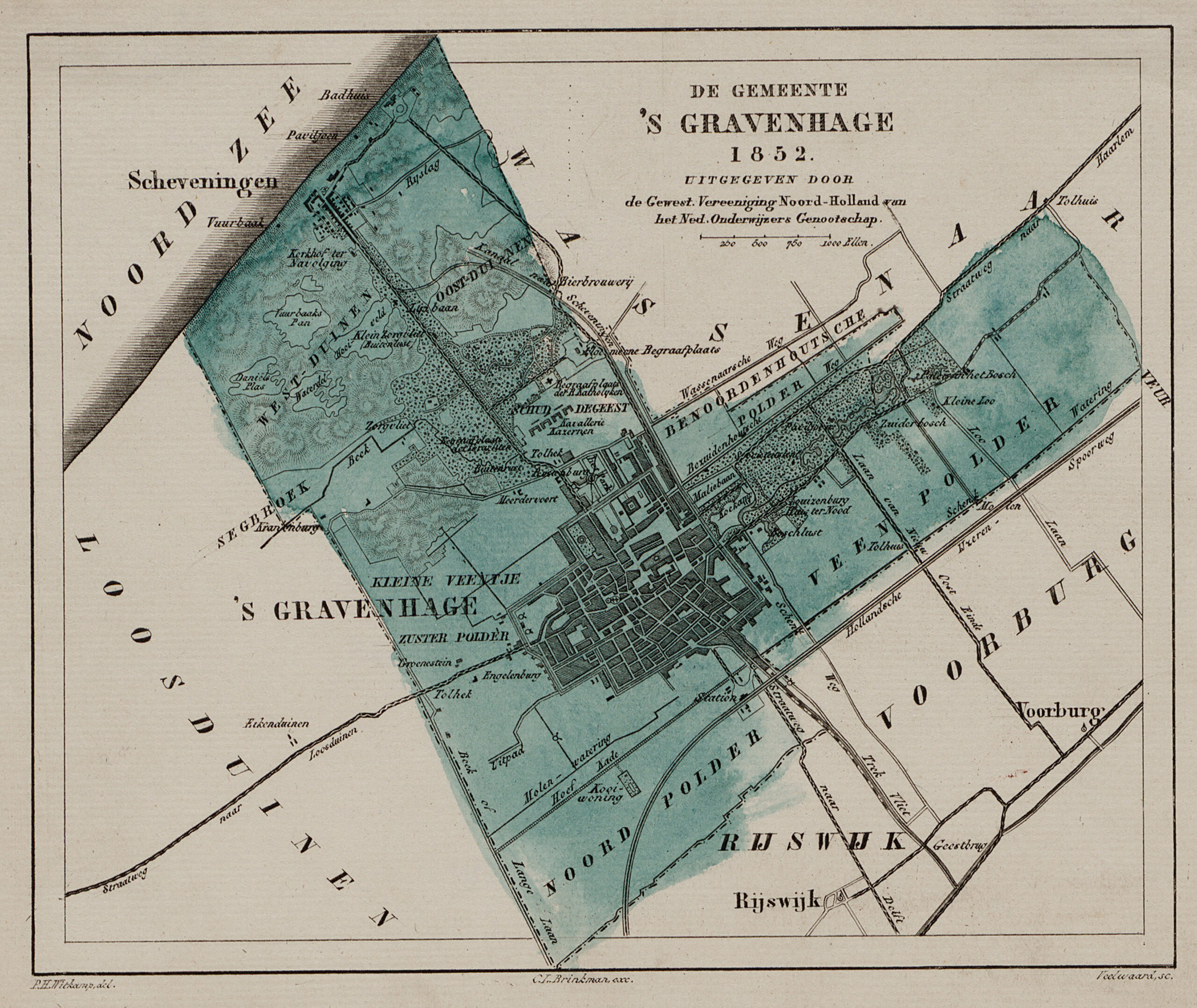

The new city map of The Hague and Scheveningen

City architect Zeger Reijers (1819-1874) meticulously drew on the city maps in 1833 and 1835 all the great monuments of the city andlinden trees individually on squares and along quays while the slums in the courtyards were left white, as if they were not there. In the second half of the nineteenth century, The Hague transformed from a smelly dark water city into a dry, lit, hygienic service city. This wasaccompanied by numerous conflicts of interest between citizens, hygienists, the city government and the seaside resort. For the inhabitants of The Hague, the miserable life in the slums of the people from The Hague and the Scheveningen in the second half of thenineteenth century was made visible by a new way of drawing city maps by hygienists. In addition to the progressive newspapers, whichconstantly reported on the abuses in the slums, it was mainly the city map and the statistical data that made it visible to residents of The Hague what was going on in the slums in the courtyards. The city image of a hygienic city was born and the entire second half of the nineteenth century would be fought for in order to achieve truly healthy homes and urban spaces with modern architecture and urbanplanning in the twentieth century.

Following in the footsteps of physician Johannes Wilhelmus Schick (1818-1853), whose study Over den gezondheidstoestand van ’s Gravenhage (On the state of health of The Hague) was published in 1852, the city architect Willem Cornelis van der Waeyen Pieterszen(1819-1874), who took office in 1853, had the city maps drawn differently from his predecessor Reijers. During the Restoration, inner areas were preferably not drawn by Reijers cum suis and the city was presented as a collection of magnificent monuments. Thesemonuments were often drawn in revolt or redrawn in the lace decoration. Often, they were enlarged on the city map, so that there wasno doubt about the prominence of the palaces and important urban facilities. For example, the city maps of Reijers (1833), Reding(1837), Van Stockum (1839), Zürcher (1844), brothers Belinfante (1847) testify to this old way of drawing.

Van der Waeyen Pieterszen broke with this tradition and was the first to meticulously record the slums of The Hague and Scheveningen.These were then used for the new generation of maps of The Hague. For example, the city map by Elias Spanier (1858), Last & Lobatto (1868), Verstijnen & Van der Waeyen (1873) and Verstijnen with the design for a sewer plan (1876). Especially the city map from 1868 measured by C.E. Last, surveyor at the land registry and drawn and stoned by J. Lobatto on behalf of the Vereeniging tot Onderzoeknaar de Middelen ter Verbetering van den Gezondheidstoestand der Gemeente ‘s-Gravenhage (1866- 1872) meticulously showedall the slums. Given the large circulation of the lithographs, these maps must have played a role in the process of raising awareness of what took place in the slums. Van der Waeyen Pieterszen had been concerned about the city’s sewers and drinking water supply for some time and argued: ‘… The need for good drinking water is increased and increased by the alarmingincrease in the construction of courtyards and the accumulation of dwellings and people who have to search for their water in the middleof the city.’ (Stokvis, 1987: 35). This new way of drawing city maps and the enlightened ideas of Schick cum suis must be seen within the social developments and upheaval of the polity with Thorbecke (Oorschot, 2021).

During the second half of the nineteenth century, enlightened citizens increased the pressure on the city government to come up with legislation and urban facilities. But changing the city wasn’t that easy. Certainly not because The Hague experienced explosive growthand there was even a catch-up compared to big cities Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Because after the introduction of the Municipal Act (1851) only very wealthy citizens of The Hague were on the Hague council who mainly tried to reduce municipal expenditure, this washardly heeded. Under pressure from public opinion, the municipality reluctantly granted concessions for utilities, often to foreigninvestment companies that often-demanded sole dominance over this supply as a condition. The city council thought that suchconcessions would reduce expenditure, but it became increasingly clear that it was a very expensive facilities or amenity for the citizens (Bakker Schut, 1939) (Gemeente ‘s-Gravenhage, 1948) (Stokvis, 1987) (Buiter, 2005).

In addition, the coherence between different urban facilities and amenities was complex and the interests were high. All choices in favorof one particular amenity had immediate consequences for other amenity. For the sewer system, a water supply network was needed torealize the flushing system. Sidewalks gave the opportunity to build street sewers. Main sewers were laid in the filled-in canals and tramroutes above them. The Renewal Canal was needed to be able to discharge the sewers at sea, which led to a conflict with the shipowners and the seaside resort. With the construction of the ports, the need to use the canals as ports disappeared and they couldbe filled in. In short, all decisions interlocked.

In 1875 the city architect Van der Waeyen Pieterszen passed away and was succeeded by B. Reinders as city architect who would stayon until 1890. For the engineers and doctors of The Hague, the change of the city was an endless puzzle hindered by its own administration. After 1887, the way was cleared to make urban facilities a municipal task and the city came into the hands of engineersand architects. The city had changed from a smelly dark water town in 1850 to a dry ly lit hygienic service town in 1900, despite the municipal administration.

Conflict between hygienists in The Hague and the city council - 1852

The cat was thrown among the pigeons by physician and hygienist Schick with his publication in 1852. He made a direct connectionbetween soil conditions, urbanization and epidemics with the case of The Hague (Schick, 1852) (Bakker Schut, 1939) (Oorschot, 2021).In his publication, he pointed out the risk of contamination of drinking well water and rainwater because of the landfills and manureheaps in the vicinity of pumps. After the epidemic of 1849, many more would follow. The cholera years were: 1849, 1853, 1854 and1855; and the typhoid years: 1856, 1857 and 1858. The explosive growth of the population, the densification within the canal and the filling of slums were accompanied by continuous epidemics, and that put pressure on the city council to do something.

Everywhere in Northwest Europe, hygienists made themselves heard. Using statistical research, they tried to demonstrate a linkbetween diseases and social differences (Houwaart, 1991) (Ladd, 1990). These hygienists were individual doctors and engineers whofocused on improving public hygiene, public health and the living environment. Equal quality of medical assistance to all was the aim.Insights from England and France, where urbanization had already taken place, were brought to the Netherlands by enlightened citizenssuch as Schick. Schick went a step further and showed with a statistical study in the province of South Holland that, if everyone receivedequal medical care, there were still large differences in people’s health.

There was a link between landscape geomorphology, urbanization, quality of houses and epidemics, Schick showed. In rural areas, themortality rate was much lower than in urban areas. Schick concluded: ‘The observation that the mortality rate in different places, which are spread over a certain extent, shows a very striking similarity, leads to the conclusion that there are circumstances which influencethem over a certain space.’ (Houwaart, 1991). Schick even observed that there has been a significant deterioration since the eighteenthcentury. With his statistical method, he also made visible the causes of the deterioration: inadequate sewers, toxic vapor of canals with rotting substances and stagnant water, accumulation of dwellings in the courtyards, the lack of sanitation, overcrowding, insufficientcleaning of the streets, spoiled drinking water and contamination of the soil with organic substances, houses built directly on the moistpeat soil without it being excavated and replaced by sand, damp building walls, no ventilation and no daylight in the houses in the slums,and canals like open sewers full of impurities.

Schick’s findings focused on geographic space. Schick advocated a technocratic approach to the problems in which the hygienistsshould be given control over public hygiene and regulations for housing and street layout. In addition to the link between the city and disease, the link between drinking water supply and contamination was undeniably established, but the city council was silent and believed that the solution to the problem was found in government abstinence and that the free market did its work in this. Schick’s recommendations for housing construction were: ‘To have all the construction carried out according to a fixed plan, taking into accountthe height of the ground, the nature of the ground, the design of the streets and the distance from the dwellings with regard to the height;In the incorporation of dwellings to take into account good ventilation, lighting, heating and construction of the houses as well as of thesanitation, sewers and gutters; To regulate the size of the houses according to the number of inhabitants.’ However, theserecommendations were also overruled by the city council. In 1853, less than a year after Schick’s research and in the year of the appointment of Van der Waeyen Pieterszen, there was another cholera epidemic in the slums in The Hague and Scheveningen. Theyoung physician Schick himself would die of typhoid fever that year.

The KIVI and the fear of degradation on the civilized classes - 1854

In 1854, by order of the king, engineers from the Royal Institute of Engineers (KIVI) wrote a report on the state of housing, which waspublished a year later as: Verslag aan den Koning, over de vereischten en inrigting van arbeiderswoningen, door eene commissie uit het Koninklijk Instituut van Ingenieurs (Report to the King, on the requisition and interior of workers’ houses, by a committee from the RoyalInstitute of Engineers) (KIVI, 1855). The Hague engineer and trader in building land Johannes Bartholomeus Maxwils (1811-1881), whowould later develop the better parts in the Zeeheldenkwartier and the Archipelbuurt, inspected the slums in The Hague for the KIVI andconfirmed Schick’s findings. In his conclusions, he went a step further and argued that there this was not only the cause of sickness andmisery, but also of immorality, which would eventually affect civilized classes.

‘Limited in space, often poorly lit, imperfectly sheltered from the influence of the atmosphere in damp places and in corridors andalleys, not supplied with the much needed. Without a supply of abundant water, without the discharge of the most hideousuncleanness, the workman’s dwelling is not infrequently a place of terror for the more civilized, where uncleanness sometimesrises to the top, the atmosphere is ruined by all that is piled and rigged, where immorality finds its cradle and cradle, and wherethe foci of diseases arise, whose influence spreads widely around, to attack all classes, and to cause the scourge of destructionto go around into the homes of the more civilized.’ (KIVI, 1855)

The report was not only limited to the old houses but also to new homes, Maxwils complained about the system behind this housingconstruction: ‘Little or no attention was paid to the location and humidity and only intended to build many homes with little money.’ Thehouses were too low, often the wooden floor was only 20 cm above the water, there was no bottom closure, the masonry was poor, therooms too small and too small in height, and there was no air flow. Homes were built too low in unexcavated peat. There was no cleansand layer, no drinking water, no sewer, no sanitations, no daylight and epidemics of typhoid and cholera broke out constantly.

Association for the Improvement of Housing of the Working-class - 1854

A number of prominent citizens and members of the KIVI were concerned about the fate of the people in the slums. In 1854 theyfounded the first housing association in The Hague: Vereeniging tot Verbetering der Woningen van de Arbeidende Klasse.(Association for the improvement of Housing of the Working-class). The driving force was Isaac Paul Delprat (1793-1880), anenlightened officer and engineer who was trained in Paris at the École des ponts et chaussées and was commander of the MilitaryAcademy in Breda and also a board member of the KIVI (Dirkzwager, 1979). The articles of association set out the following ambitions:

’the construction of new dwellings furnished separately for each household, in order to rent them out at a fair price; the purchaseof poorly furnished houses, either so-called blocks or individual dwellings in order to improve them as much as possible and thento rent them out or, if necessary, to resell them; to take all such measures as are within its reach to promote the health of the inhabitants and the potty training, especially by urging improvement in this respect from other owners or from the Government; inconnection with this, to improve the morality of the inhabitants by all means which experience shall designate as effective.’ (BakerSchut 1939: 4).

Later this association changed its name to: Koninklijke Haagse Woningvereniging van 1854. The association included Hofje vanSchuddegeest from 1854 by Saraber, Mallemolenhofje from 1868-69 by Jager and Van der Kamp, Paramaribohofje from 1881 by Wesstra, the 42 residential blocks at Van Hogendorpstraat 52-162 from 1862/69 by Saraber, the Red Village from 1874, the Delprathouses from 1897/98 by Van der Poll.

In the year 1854, a committee of the city council was instructed to ‘Ordinance on building within the municipality of The Hague’ and ’to make a general plan for relatively all the expansion of the city, all the construction of new streets, squares, etc. in order to test allsubsequent plans and applications in this regard against that plan.’ (Baker Schut, 1939).

As argued, cities such as Rotterdam and Amsterdam already had an expansion plan in the second half of the nineteenth century. In1859 Van der Waeyen Pieterszen suggested a Algemeen plan van Uitbouwing der Gemeente (General Plan of Development of theMunicipality), but it did not go beyond partial plans for the Northwest and Southern part, of which due to the ownership relationships andthe impossibility of expropriation, nothing ultimately came to fruition. The municipality itself was too busy with the Willemspark, whichwas built at municipal expense during this period and whose building plots were sold. Just like the expansion plan, nothing came of abuilding code or regulations that Schick had insisted on. Unsurprisingly, at a council meeting in 1859, councilor De Pinto dismissed allthe arguments of the medics and the engineers and opined:

‘I do not dispute that it is very desirable that houses should be built healthy and well, but I may trust that those who have housesbuilt will understand this in their own interest, but it is equally useful to have good clothes and good food. It is not possible toprovide for everything in this matter by Police Regulation. It is said that it is in the interest of public health. I cannot see this: it mayaffect the health of the individual who occupies the house, but it is not so for others. The provisions are very restrictive. Peopleare under illusions, they follow Amsterdam and Rotterdam, where these provisions have been put on paper, but have never beenimplemented, because it was not possible.’ (Baker Schut (1939: 8)

Instead of the intended building ordinance, some very fragmentary regulations were eventually incorporated into the Algemeene Politie-Verordening (General Police Ordinance) (Chapter IV of 1860). It was accepted that there had to be a ratio between the width of a streetand the height of a building. The minimum thickness of the building wall was set at 22 cm and a minimum height of 250 cm for a livingroom was approved. The ban on the construction of back-to-back housing was rejected by the city council by a vote of 28 to 6. The wishthat each house should have its own sanitation was invalidated by a dispensation power of the mayor and aldermen: one toilet perperson for every six houses was included in the ordinance. The regulations on the thickness of the building walls were not declaredapplicable to the slums to be designated by the mayor and aldermen; those of Scheveningen were immediately designated, according toBakker Schut (1939).

Associations for health improvement - 1866-1908

In 1865, sixteen physicians wrote a letter to the city council in which they again expressed their concerns about the health of thepopulation, but this was set aside for notification. A year later, in 1866, the next cholera epidemic broke out. In that year, the Vereeniging tot Onderzoek naar de Middelen ter Verbetering van den Gezondheidstoestand der Gemeente ‘s-Gravenhage(1866-1908) was founded, an association that had a major influence on the hygienic development of The Hague (Bakker Schut, 1939). The association changed its name a few times during its existence: in 1871 it became Vereeniging tot verbetering van de gezondheidstoestand te ’s-Gravenhage; in 1903 Het Hygiënisch Genootschap te ’s-Gravenhage; in 1908 the association wasdissolved. Bakker Schut argued about the status of the association that:

‘Year after year, this association mercilessly exposed the hygienic abuses, and although it could not rely on the approval, let aloneappreciation, of the city council, especially in the first two decades of its existence, one got the impression that it was not leastthanks to it that better concepts of public housing and hygiene began to take hold. The association gave unsolicited advice to the council and in 1867 sent the foundations for a building ordinance to the city council’ (Bakker Schut, 1939: 11).

Important points were minimum street width of 10 meters. Height of the houses does not exceed the street width. Each house musthave at least two rooms, of which one room at least 25 square meters in size. Minimum height living room 3 meters. Separately toilet foreach dwelling discharged into a sewer or watertight cesspool. Prohibition of closet-bed. Obligation to make a waterproof masonry ofdouble baked brick from the foundation to approximate 60 centimeters above ground level. Some demands were met and others werenot. The only physician on the city council, Mr. Dr. P. Bleeker, raised the housing issue again at the council meeting of March 26, 1867.On his ‘cholera map’ all deaths were recorded and located (Van Doorn, 1991: 19). Once again, Bleeker made an unequivocalconnection between housing conditions, geography and cases of illness at the council meeting.

‘And now it has struck me very much that even in the more afflicted neighborhoods, the main streets and canals and moderatelyspacious streets have suffered very little from the epidemic and that the unfavorable mortality ratio even in those neighborhoodsis mainly due to the numerous courtyards, slums and corridors and alleys, often localities with limited airflow outside and virtuallyno air flow inside the house.’ (Bakker Schut, 1939: 9).

Bleeker suggested appointing a council committee to investigate what could be done to improve public housing. The proposal wasadopted and a committee appointed. Bleeker resigned as a counselor a few weeks later and on 7 May 1867 the committee wasdissolved without a vote or discussion in the council (Bakker Schut, 1939:9) (HGA bnr 0036, inv.nr 1-39 ‘Vereeniging Verbetering Gezondheidstoestand’, 1866-1908).

General Police Ordinance - 1871, 1876, 1878, 1884, 1892

Between 1866 and the advent of the Housing Act in 1901, the associations of hygienist were able to amend the Police Regulations stepby step with constant pressure. In the years 1870 and 1871, smallpox epidemics broke out again in the slums. Two years later, in 1873,there was another cholera epidemic. It was not until the General Police Ordinance of 1871 that the flawed bylaw of 1860 was revised.The Association for the Improvement of Health Status was disappointed in this reluctant admission and turned to the city council again,but was not heard. Nevertheless, two articles 44 and 45 were included that would become important for the city, according to BakkerSchut (1939: 12). ‘No one may build higher in new streets than determined for each street by the City Council. No one may build a streetexcept to be determined by the City Council on its width and in the direction.’

In the street layout after 1875, articles 44 and 45 on the city interpretation of the General Police Ordinance of September 19, 1871 and June 20, 1876 were incorporated in council reports and agreements between the municipality and the building-land-companies. Thesestandards applied to all neighborhoods. However, there were no monumental ronds-points with fountains or beautiful streets with linden trees in working-class neighborhoods and the streets there were often narrower than the police ordinance prescribed. Ten meters or lesswas common, while twelve meters was the prescription. In the layout of streets, various articles of this ordinance from 1871 would playan important role. These were provisions that related to the size of the street and height of the façade, but what took place in the courtyards and the slums, was still considered of no importance by the council.

Another article, labeled as eccentric by Bakker Schut, dealt with toilets. In doing so, the old dispensation power was repeated by themunicipality. Each home must have a toilet unless one has a permit to make a common toilet for every six homes. The associationopposed this article which gave a dispensation power. This was a continuation of the old policy; the Criminal Procedure Commission ofthe municipality gave the following curious answer: ‘The Commission dares to express the opinion that one toilet for every six small houses outside in a narrow environment is healthier than having such an opportunity for every small house inside.’ The associationresponded to this curious statement that one toilet for six homes meant, one for twelve families, one for every sixty persons. However,the council accepted the opinion of the Criminal Procedure Commission.

At the urging of the Vereeniging tot verbetering van de gezondheidstoestand te ’s-Gravenhage, the first building regulations weredrawn up in 1878: ‘Regulation regulating the building police’. For the first time, doubts were also expressed in the city council about theHague courtyard system. Councilor Rietstap argued on April 10, 1877 that the first courtyards were founded by friends of people, withthe aim of meeting the needs of less fortunate fellow citizens. The courtyards of the new age, on the other hand, are merely means ofspeculation and exploitation. From now on, building plans for courtyards had to be submitted to the municipality for approval. Thedistance between the facades had to be at least 6 meter and the height of the living quarters at least 260 centimeters. People wereallowed to build houses back-to-back, a gate to the courtyard was allowed and the communal toilet per six houses remained the rule.

In 1882, a committee from the association consisting of Dr. Carsten, Ir. D.E.C. Knuttel and Dr. A.H. Pareau reported on the changesdeemed necessary in the revision of the regulation. The Criminal Procedure Commission, when the Ordinance was revised in 1884,informed the association: ‘and with regard to the further construction and interior of dwellings, the Commission considered that, however desirable it may be, that the health measures recommended by the addressees should be observed, the prescribing of such measures, under threat of punishment, would be highly restrictive and impossible to maintain, since it would restrict the freedom of residents in avery questionable manner. As long as the need to restrict freedom in the public interest has not become apparent, no further than isnecessary may be taken in this respect.’ (Baker Schut, 1939: 13). That is the liberal position of the committee. In a new revision in 1888, only an access of 250 centimeters wide and 300 centimeters high was added to the articles of the ordinance, otherwise everything interms of building legislation remained the same.

In the year 1892, during a revision of the police ordinance, article 41 of Het Stedelijk Keur of 1841 was abolished, the law that left the building in the courtyards and in the meadows to the free market without regulations and subjected the facades on the streets andsquares to all kinds of requirements. Het Stedelijk Keur was replaced by an article that prohibited ‘building other than on streets, laid outon site, according to the dimensions in the direction and at the height determined or approved by the City Council.’ (Baker Schut, 1939:13, 14). They were not allowed to build more than ten meters behind the building line. After 51 years, construction working-class units and slums in courtyards and on empty meadows came to an end. A year later in 1893, the journalist Gram argued about the livingcondition:

‘So, a lot depends on whether the Hague City Maiden is seen first from the front or from the back. … Dr. Pareau, who recently in The Hague press denounced the layout of the numerous narrow and musty alleys with low workers’ houses, so-called ‘courtyards’, on hygienic grounds disapproved, found in all these iniquities reason to compare the court city with someone whoonly washed face and hands. There is much truth in this witty chosen image. Indeed, The Hague City Maiden needs the spaciouscloak of love to cover it, which is neither beautiful nor attractive. She appears neat and elegant, kind and brightly, but when shecarelessly lifts her tunic a little high, things come up that make you blush greatly.’ (Grams, 1893: 18, 20).

Coal, coke, gas lighting, sanitation, electricity and communication

As for utilities, which also covered the better parts of the city, the city government was more lenient than it was regarding regulationsregarding the health of city dwellers. Around 1840, the open fire of wood and peat was replaced by stoves, stoves and cooking stovesthat burn coal with a significantly higher energy yield. Gas could also be made from coal, which was important for street lighting. Theresidue left behind during degassing was called coke fuel. As early as 1774, the streets of The Hague were illuminated with 1659 oillanterns. In 1820 the first gas lighting appeared on the Binnenhof (Stokvis, 1987).

In 1843 a concession was granted for thirty years for municipal gas lighting to a stooge of the Anglo-French banker and speculator Neville Davison Goldsmid (1814-1875) and his ‘Compagnie d’ éclairage au Gaz des Pays-Bas’ established in Paris in 1844. The Goldsmid family was active in Paris, London and The Hague and had ties to the Rothschild banking family. The company was given amonopoly in The Hague for thirty years over the supply of the running gas, which ultimately cost the municipality dearly. The companyinstalled 880 gas lanterns at its own expense and the operation came to 40,000 Dutch guldens per year, at the expense of themunicipality. High costs and low quality were the result, according to Stokvis (1987). The municipality negotiated and litigated in vain.Goldschmid demanded three million guilders for the redemption of his concession. Around 1870, Goldsmid’s gas factory was built on theLijnbaan, where coal was processed into gas. In 1875, the concession finally expired. In that year, 2900 private customers spent morethan three times as much money on gas as the municipality.

Already in 1872, the municipality decided to set up its own gas company. Under the leadership of director J.E.M. Kos, a new municipal gasworks was built on the Loosduinseweg-Gaslaan in 1875, which began supplying municipal gas in June 1876 at a much lower price.Due to the arrival of gas stoves, the consumption of gas in the new neighborhoods increased significantly and coke and coal graduallydisappeared. In 1880 the old gasworks of Goldschmid on the Lijnbaan closed. Gas was not only used by the municipality and privateindividuals, but especially by companies that worked with gas engines. With the introduction of the coin gas meters by the year 1900, the less well-off citizens were also connected to the gas network. Due to the urban expansions, the municipality decided in 1904 to buildthe second gas factory along the Trekvliet in the Bickhorst. In 1907 it was completed and this factory was accessible to cargo ships with500 tons of coal. The First World War caused problems with the supply of coal in The Hague and these were therefore rationed.Gradually, the gas extracted from coal disappeared and was switched to electricity. In 1917, coal was so scarce that even municipal waste incineration connected to the municipal power plant.

Stokvis (1987: 38) reported that the gas lanterns were only placed in the better neighborhoods. However, Van der Haer (1968) collectedphotographs from the period 1860 to 1870 and showed that the lesser districts were also provided. Almost all urban spaces in the oldcity and new neighborhoods were illuminated, including smaller streets such as Bleyenburg and Maliestraat. The slums in ScheveningenWest, such as the Wassenaarsestraat near the Seinpostduin, were not illuminated. Another book with photos from the end of the nineteenth century also shows that alleys were equipped with gas lanterns, such as the Schapensteegje around 1895 (Nieuwenhuijzen & Slechte, 1975). Other urban spaces, such as the Lage Zand, were still unlit by 1900. A slop at the Westeinde also had no lighting. Thelesser neighborhoods, such as the old Slijkeinde and the new streets, such as the working-class streets Haveriusstraat andJacobastraat, were illuminated at the turn of the century. It could be said that around 1870 the city was completely illuminated with gaslight, apart from the slums in courtyards that were still in darkness (HGA bnr 0452 ‘Raadscommissie ad hoc omtrent de aangelegenheden der gasverlichting’, 1873-1879).

In the newspaper De Opmerker of 1867, four articles by Van der Waeyen Pieterszen appeared in which he described plans for anintegrated sewer system in The Hague on a flush basis with steam pumping stations. The rinsing water would have to be supplied bythe city bosom, but a drinking water network was also needed to flush the sewers of the houses. The waste water of the sewers wouldthen have to be directed to the dunes as fertilizer. Unfortunately, they remained intentions (Buiter, Riool, rails en asfalt: 80 jaar straatrumoer in vier Nederlandse steden, 2005).

In addition, there was disagreement in The Hague about whether to install an integrated sewer system based on water flushing or the Liernur system in which faeces were sucked out of the piping system by means of negative pressure, for which no water pipes would beneeded. Still, the malodorous canals and dirt in the streets must have troubled the gentlemen of standing. The beautiful city image wasmarred and the city council decided that this junk had to be picked up. Private individuals who tendered the lowest in the tender pickedup the dirt in the city by handcart and barge and deposited it outside the city (Stokvis, 1987). This was not always done carefully and in1871 the municipality took the city cleaning into its own hands. The cleaning service was equipped with new equipment: horse and cartentered the service. The stench of the canals, the epidemics, the system of partial sewer systems with settling pits and discharge to thecanals remained a problem. From 1908, dump trucks were put into service and in 1912 the first garbage trucks appeared, first onelectricity and later with gasoline engine (HGA-bnr0394 ‘Gemeentelijke reinigingsdienst’, 1871-1969).

The construction of a drinking water supply network was promoted by the Vereeniging tot verbetering van de gezondheidstoestand te ’s-Gravenhage (HGA-bnr0395 ‘Ingenieur van den eerste aanleg der Duinwaterleiding’, 1871-1874) (Stokvis, 1987). Finally, in 1873,money was borrowed for the construction of this facility. Previously, public wells, pumps or lead-lined cisterns were used to collectrainwater. Small households involved hot water at water and fire stores. As early as 1863, several private concessions were applied forbut not granted or realized. After proposals by councilor De Pinto for municipal construction were rejected in 1866 and 1869, hisproposal was accepted in 1871 by 18 votes to 11, while two years later it was also decided that the municipality to operate the system. Under the direction of the chief engineer of the State Railways J.A.A. Waldorp and the Norwegian engineer Th. Spang, trained in Liège, the construction went well in 1874: in January 1875 there were already 1002 connections.

Foreign entrepreneurs also played a key role in this facility. A London firm laid the pipes. In 1874 the total length was 64,000 meters andin 1912 almost five times that. Consumption increased faster than expected due to the installation of fire hydrants in the city and the annual rate for homes that was adjusted to the rental value.

Only when waste was prevented by regulating the pressure and in 1884 the collection in open canals gave way to fine sand drainage in the dunes, which also reached deeper from 1890, did municipal exploitation of drinking water become profitable. The water supplynetwork from the period 1873-1875 made the integrated flush-based sewer system possible. Now the houses with water connectionscould also flush the sewers. A map from 1874 is known on which a sewer system was drawn in 1876 by the city architect Reinders, witha pumping station to discharge water into the sea; a refined sewer plan, in which all streets of the city were given a sewer (HGAgr.2030). On October 14, 1879, the city council decided with a narrow majority not to build a sewer system but large sinkholes in the Spui and Prinsegracht to be filled in (HGA-bnr0451 ‘Raadscommissie tot onderzoek van het riolenplan of rioolstelsel’,1875-1887).

As early as 1876, the International Bell Company requested that a telephone connection be established and operated. In 1880 thecouncil considered this request. According to the pre-advice to the city council, the municipality did not need such a facility, but somecouncil members thought very differently (Stokvis, 1987). Bell’s Dutch subsidiary was prepared to invest in the overhead lines, but inreturn demanded the exclusive right for a number of years. In 1883 there were already 116 telephone connections and when theconcession expired in 1897 there were 607.

After many meetings and much opposition from the city, it was not until 1902 that it was decided to operate the municipality. Thetelephone service became an independent municipal company that expanded rapidly. Cables came together in telephone towers thatwere connected to the telephone exchange with an underground cable. In 1903, the municipal telephone service already had 2032connections and became a profitable municipal business. In 1885, W.J. Wisse, deputy director of the Rijkstelegraaf, received a limitedconcession to build a power station. The Hofsingel power plant, completed in 1889, was taken over by Siemens in 1891. Consumptionwas small-scale and some companies and hotels had their own power stations.