2 - Theming the cityscape of a village in the leafy greenery

2.1 - City Image as Legitimation of an Administrative Status

"Europe's richest, most beautiful, and largest village"

The Hague is unfortunately and high against the dune rows in the corner of Holland located and has never had the luxury of shippingand trade routes. As a result, it could never develop into a classic Dutch water and trading city such as Rotterdam, Delft, Leiden,Haarlem, or Amsterdam. It never got city walls or real city gates; the canals were only dug in the seventeenth century. The Haguealso did not receive city rights in the Middle Ages. This geographical omission would strongly determine the character of The Hagueand be used in the city image to distinguish itself from the ‘real’ cities. In 1567, the Italian-Antwerp merchant and humanist LodovicoGuicciardini (1521-1589) visited The Hague and described the village in his book Descrittione di tutti i Paesi Bassi, altrimenti dettiGermania inferiore (1567) as:

“The Hague was undeniably Europe’s richest, most beautiful, and largest village. Where did you find an open village with suchbeautiful hiking places as the leafy Vijverberg and the neat, orderly planted Voorhout?” (Stal & Kersing, 2004: 67).

The description in the quote above was provided with a map entitled Gravenhaghe, T’ hoff van Hollant and shows a village with roadssurrounded by orchards and gardens. In this bestseller, Guicciardini repeated the image of The Hague that had been common sinceCount Albrecht van Beieren (1336-1404): a distinguished village in leafy greenery. A neutral administrative village between powerfulcities of merchants. Between 1422 and 1425, court painter Jan van Eyck (1390-1441) painted a fish party in the Hague stream withthe court and the Voorhout in a paradisiacal green environment in the background (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Not only the much-vaunted tree-filled Hofkwartier that connected directly to the Haagse Bos was a paradisiacal environment, but the village must alsohave looked like this.

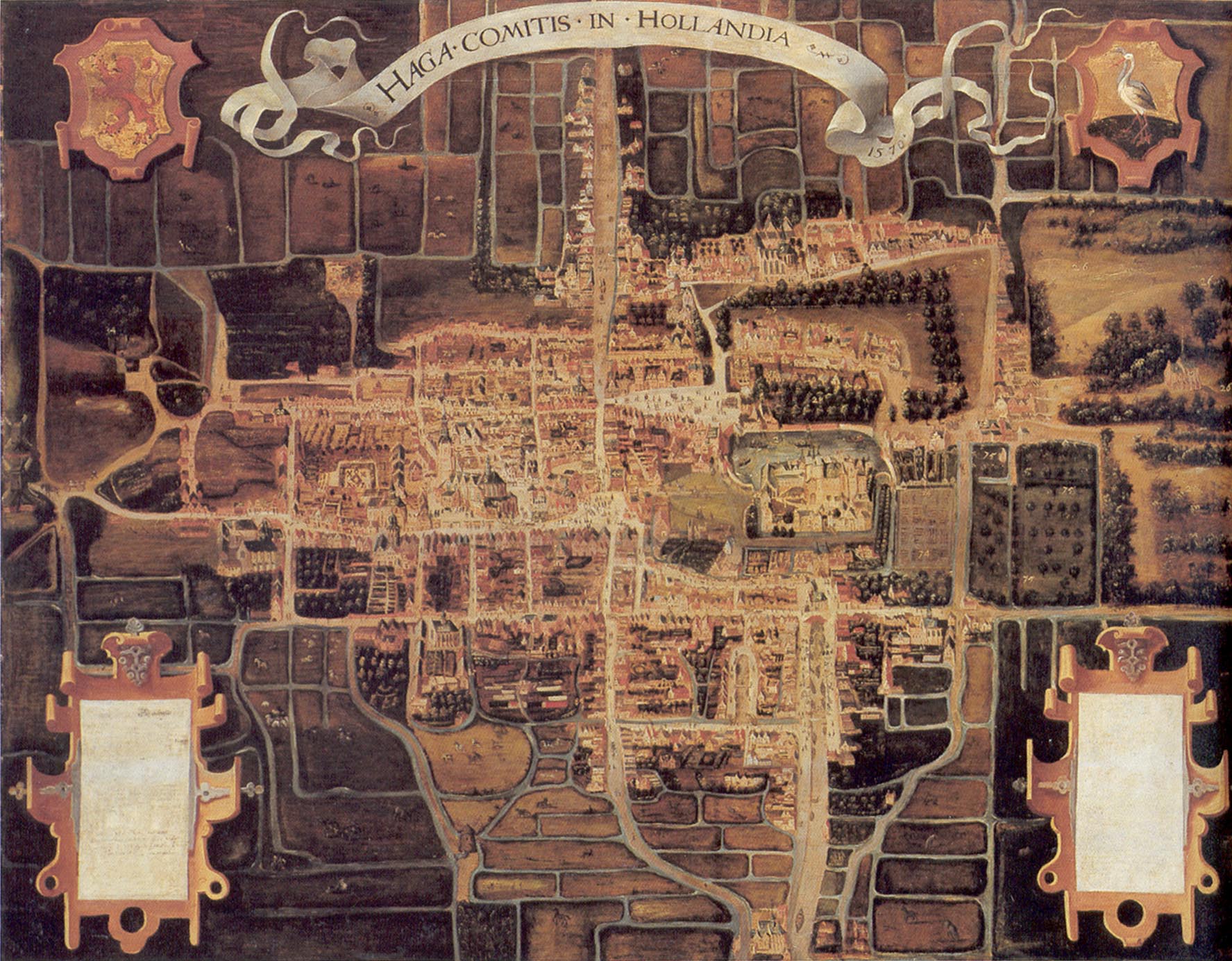

The village of ‘die Haghe’ had no less than four monasteries with extensive market gardens and orchards. The village itself with itsunusually spacious courtyards with gardens and orchards must have reinforced the image of a village in the leafy greenery. Becausethere were no city walls and canals, the village could grow freely along roads and take up space for courtyards. The Voorhout and the Vijverberg with the spacious city castles grew into the first green suburb of Holland. After 1470, all developments stagnated so thatthe paintings of a hundred years later give a true picture of the village from the time of Albrecht and Jacoba van Beieren. In 1553, the painting of the Hofkwartier ‘Haga in Hollandia’ by an unknown painter repeats the exaggerated pride of the inhabitants in front of theleafy greenery. Just like the painting by Cornelis Elandt’s Haga Comitis in Hollandia from 1658, a copy of an older painting from ca. 1570. Both paintings are in the Haags Historisch Museum.

Other paintings from this period also confirm Guicciardini’s words and show a spacious and open village that was richly endowed withgardens and orchards and that connected to the Haagse Bos, for example the map of Jacob van Deventer from 1560 (HGA gr.0236) and the map of G. van Giesen from 1730 (HGA gr.0239) where the situation in 1570 is depicted.

This glorification of a city image was a flight forward, after all The Hague was a distinguished and neutral village for administrators. Itcouldn’t and shouldn’t be a city. It therefore had no city walls, canals, gates, and towers. It could not compete with Dutch merchantwater cities such as Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Haarlem, Delft or Leiden.

The creation of The Hague into a distinguished village in the leafy greenery was the result of the complex geomorphological andgeopolitical conditions. The interplay over a longer period between what made the landscape possible and impossible and the presence in certain periods of the Court that wanted to stand neutrally between the cities. Due to its location high against the dunes, The Hague was also unsuitable for growing into a Dutch merchant water city, but it acquired its distinct character because there wasno other way and because of the fortunate coincidence that the court appreciated this (Van Doorn, 1991; 1998) (Stal, 1998, 2005)(Stal & Kersing, 2004) (Stal, Groenveld & Penning, 2007) (Smit et al., 2004).

Outside the court, the village and the monasteries, an ensemble emerged that has remained iconic to this day, the first green suburbof Holland with the Voorhout and the Vijverberg planted with fragrant linden trees (Wijsenbeek-Olthuis, 1998). Because The Haguewas a village, it would have no voice in the States of Holland and would have a say in state affairs. Something that other cities (18votes) also liked. Villages such as The Hague were represented by the nobility, also called the Knighthood (1 vote). The Hague had alot of nobility among its inhabitants who lived on the Voorhout and around the Vijverberg in the leafy greenery.

The Golden Age, Status and Power

Stadholder Maurits van Oranje

Not everyone believed in neutrality and green. Stadholder Maurits van Oranje (1567-1625) chose The Hague as his residence anddreamed of developing it into a real fortified city. From the Southern Netherlands, many prominent Protestant refugees came to TheHague, who brought the court culture with them, such as Van Aersen, Huygens, and Stevin.

These families were loyal to the Oranges and were far from the Dutch merchants and mainly propagated continental politics. Moneyand support from wealthy southern Dutch citizens and the land to carry out the ramparts and waterworks were there. Part of the planswould be carried out on Maurits’ own domains. However, due to the actions of the States of Holland, nothing came of it. The pro-French Oranges advocated a continental policy in which the interests of the Oranges were central and the war with Spain had to goahead.

The Republic of trading cities and merchants saw nothing in this belligerent policy. As a politically feasible alternative, canals and aport neighborhood were constructed with an orthogonal structure. With all the sub-plans that followed, it seemed that the ideal gridcity of Maurits’ confidant and teacher, the Hagenaar and mathematician Simon Stevin (1548-1620), was implemented. The Haguewould never become a real fortified city. In the meantime, the green urban spaces were surrounded by a completely new type ofbuildings.

Pavilion houses

A new tradition from France to build city palaces according to pavilion model was introduced by these new residents (Meischke, Rosenberg & Zantkuijl, 1997) (Wijsenbeek-Olthuis, 1998). These were block-shaped houses with a pavilion roof, a roof with four roofshields and a roof rich parallel to the facade. These blocks were re-connected so that there were palaces of three or more pavilions.Hofwijck van Huygens and the Mauritshuis are examples one pavilion. The Amsterdam architect Hendrick de Keyser is probably the master builder of the House of Oldenbarnevelt (1611) at Kneuterdijk 22.

This was followed by the house of ambassador Van Dyck, later also called leprosy house (ca.1615), which was located opposite the Bierkade along the Spui. On the corner of the Lange Voorhout and the Kneuterdijk, the House of Wassenaar van Duivenvoorde(1624) was built, which was also designed by De Keyser and is an example of a pure pavilion house (Meischke, Zantkuijl & Rosenberg, 1997).

Stevin himself also lived in The Hague, in the Raamstraat in a stately pavilion house. From 1593 he was a private tutor in fortificationsand confidant of Maurice and served as an engineer in the army. In 1604 he became quartermaster of the prince. Until his death, Stevin wrote his De Huysbou, a work that was never completed but had a great influence on Huygens.

The largest pavilion house was built by ambassador Van Aersen on the Lange Voorhout. His neighbor and assistant diplomatConstantijn Huygens would later have two of the most beautiful pavilion houses built by the architects Jacob van Campen and PieterPost. Maurits’ contribution to the city itself was probably minimal, but it was mainly the circle around him that was intensively involvedin the creation of The Hague and the construction of the city palaces. Maurits would leave The Hague as a place with an orthogonalstructure, without walls or gates, but with canals, ports, and new neighborhoods where craftsmen settled. Impressive pavilion houseswere built on the Voorhout, and simple and affordable versions of pavilion houses were built in the port neighborhoods.

It was clear that not all of Maurits’ ambitions came true, but an attempt to dig a canal on the Lange Voorhout was not sabotaged bythe States of Holland, this turned out to be unfeasible due to the unruly landscape and the location on top of an ancient sand barrier or rich. Perhaps the advice of the wise Stevin, who died in 1620, was missing. Maurits’s attention was not so much in leafy green, buthe was not against it either. The city image of The Hague was steadily built on with Paris as example.

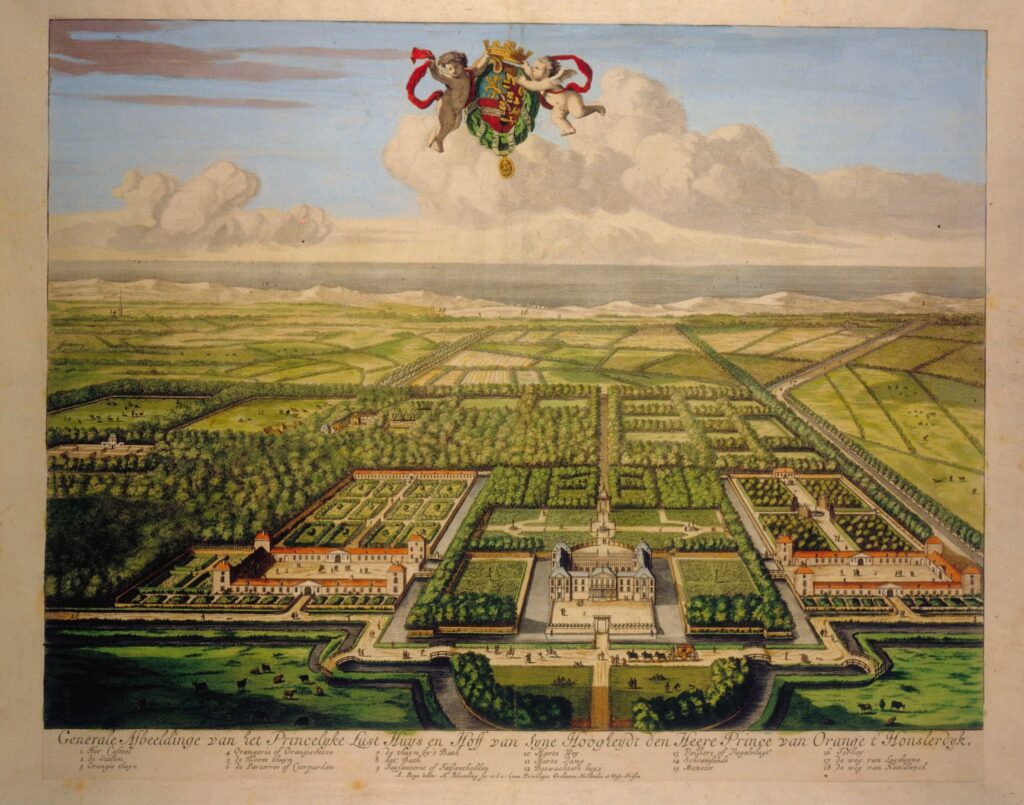

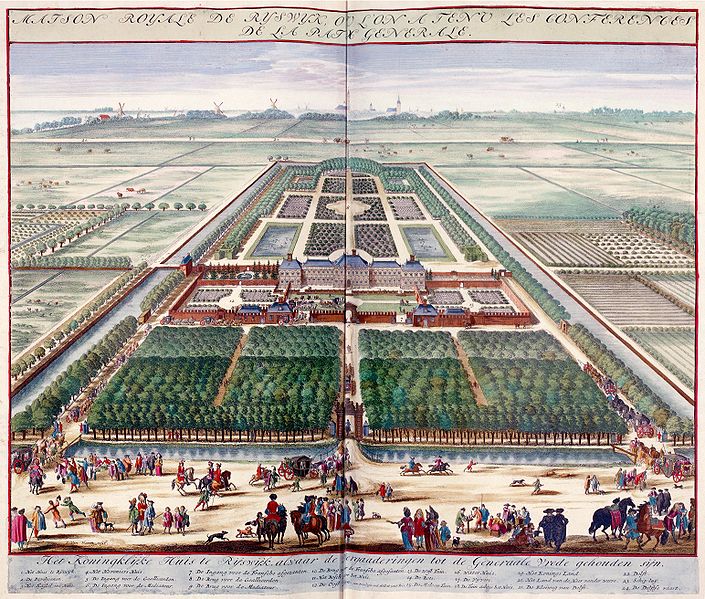

Stadtholder Frederik Hendrik

After Maurits’ death in 1625, the representative village with its park courts was firmly expanded. Country estates appeared all aroundthe village. Under his successor Stadtholder Frederik Hendrik, Prince of Orange (1584-1647), huge pleasure gardens and summerpalaces were built outside The Hague after the latest French fashion, such as Huis ter Nieuburch (1630-34) in Rijswijk, Huis ter Honselaarsdijk (1621-1640). Within the canal’s, narrow crooked streets were straightened, and re-parceled and empty gardens filledup. In addition to the city palaces that were located on the Lange Voorhout, the Kneuterdijk and the Buitenhof, geometric urbanspaces surrounded by the block-shaped spacious pavilion houses were built on Princen Plein (currently Het Plein), Korte Voorhout, Prinsessegracht, Herengracht, Prinsengracht, Boekhorststraat and Lange Beestenmarkt. From 1621 until his death in 1647, FrederikHendrik studied architectural problems almost continuously as a principal (Ottenheym, 1997: 107). The prince-stadtholder surroundedhimself with an elite that was aware of the developments in French court culture and Italian Renaissance architecture: customs, architecture, landscaping, literature, music, and painting. Especially his young secretary Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687), his clerkLaurens Buysero and his general and later governor of Brazil Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679) proved to be wellinformed. With his Batava Tempe. That’s ‘t Voor-Hout van ’s Gravenhage (1621), Huygens reminded us of a neutral administrative citywith its palaces in green. The Stadtholder’s French orientation shifted to Italian Renaissance architecture and the burgeoninghumanism in Europe. In the end, two of the most beautiful pleasure gardens with outdoors in Dutch classicism were built: Huis tenBosch (1645-52) for the prince and his consort and Hofwijck (1639-42) where Huygens retired after his prince died.

Dutch Classicism

Among the many new and influential residents of The Hague were engineers, master builders and craftsmen from the SouthernNetherlands who played a role in the introduction of new urban ensembles with geometric urban spaces and pavilion houses. Forexample, the families of Stevin, Van Bassen and Huygens came from there, while the family of the architect brothers Van ‘s-Gravesande and Noorwits came from Norwich, a place where many families had also fled after the fall of Antwerp (Ottenheym &Tussenbroek, 2011).

But it was above all the young wife of the stadtholder Amalia van Solms (1602-1675) who brought the spirit, panache and style of theFrench Court to the stiff Protestant The Hague (Van Gelder, 1937). The arrival of the Court of Bohemia in the year 1621 with the‘winterkoning’ Frederick V, Elector of the Palts (1596-1632) and ‘winter queen’ Elizabeth Stuart (1596-1662) will certainly have been aconsiderable incentive for this.

Part of the continental politics, discussed earlier, was the French alliance. The Francophile tendencies of Frederik Hendrik were andremained a sensitive subject for Dutch merchants, regents, and Protestants (Hofman, 1983). The capture in 1642 by the French of the free city of the Huguenots La Rochelle with the help of the Oranges aroused great anger. For the Oranges, this French alliancewas of strategic importance. France and Spain waged war with each other. France supported the stadtholder in his not alwayssuccessful campaigns in the Southern Netherlands against the Spaniards. During the stadtholder ship of Frederick Henry, the courtwould become an integral part of the political and social culture of The Republic within Europe.

The fate of The Hague was linked to that of the Oranges and the continental politics that were pursued. Constantijn Huygens helpedshape this as secretary, diplomat, and cultural expert. The Hague would have a special image with the many city palaces, pleasuregardens, estates, squares, and straight streets full of lime trees and the block-shaped pavilion houses with hipped roof: the image of adistinguished village in the leafy greenery after the French example. After Frederik Hendrik, the great period of The Hague andcontinental politics was over. The States of Holland and Amsterdam took over (Wijsenbeek-Olthuis, 2005). All that remained werememories of the beginning of the Golden Age. In the eighteenth, economic developments in the Netherlands and The Haguestagnated.

Yet the glorification of the seventeenth century of Frederik Hendrik and Huygens with ’the distinguished village in the leafy greenery’was not entirely forgotten. The historian and jurist Jacob de Riemer (1676-1762) recalled this image in the eighteenth century with his: Beschryving van ’s Graven-Hage, containing its origin, name, location, extensions, mischiefs, and splendor; mitzvot of the Court, ofchurches, monasteries, chapels, alms-houses, and other distinguished buildings. As well as the Privileges, Charters, Approvals andWyze der Regeringe (1730 part I, 1739 part II, republished in 1974). The well-known city image of The Hague was described in detail in it.

After the French Age, the Monuments of the Oranges

When it turned out that the village of The Hague did not pay any city tax, The Hague received city rights from King Louis Napoleon in1806 and was elevated to ‘Bonne ville de l’empire’. The city came out of the war battered and many buildings had been demolishedby owners who had moved elsewhere and did not want to pay taxes on their property. With the arrival of King Willem I (1772-1843) in1815, the old city image of The Hague was also restored. With the Belgian revolt in 1830-31, the Kingdom was reduced to thepresent-day Netherlands.

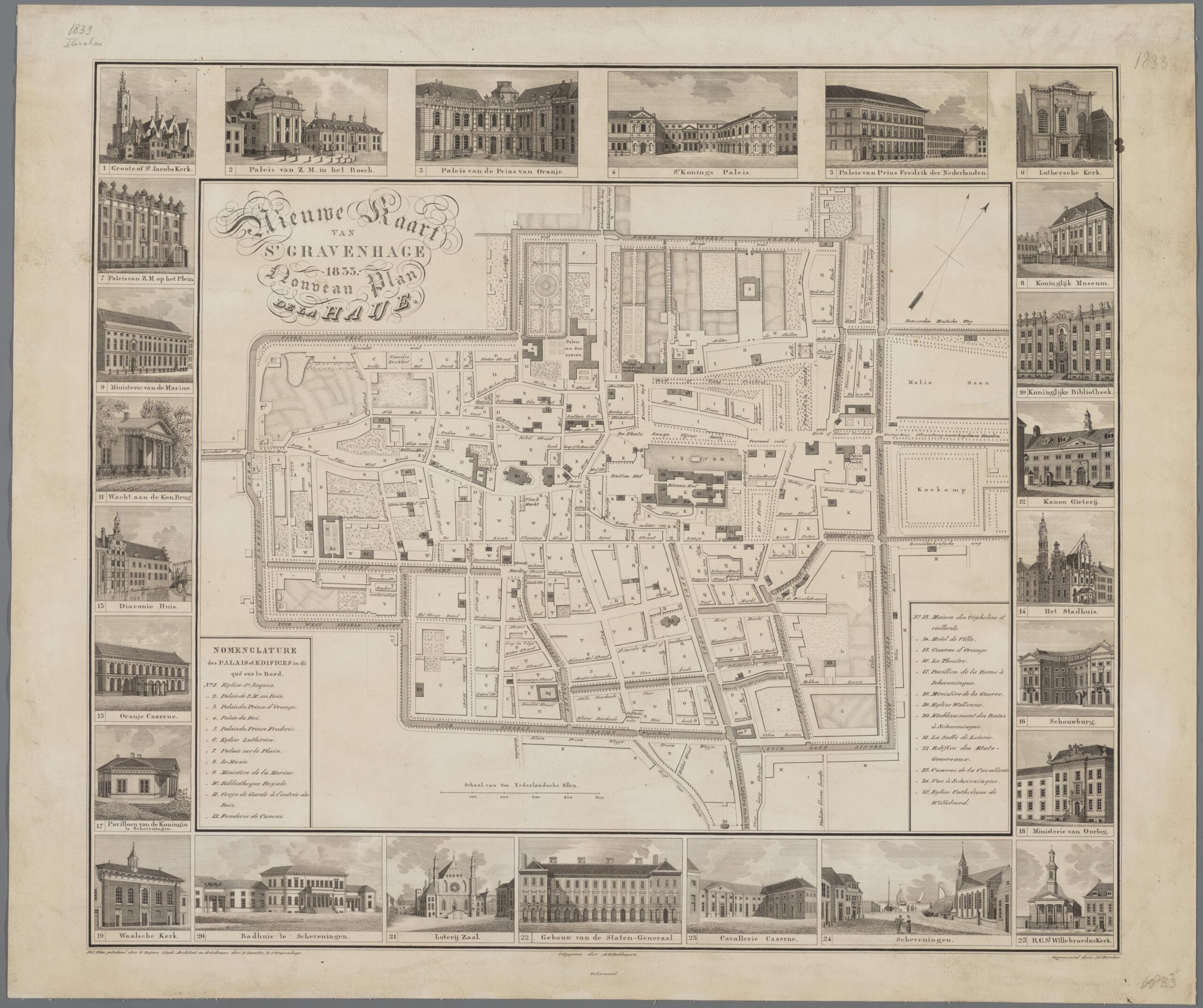

In the meantime, The Hague was gradually renovated as a residence and a representative city with monumental buildings. The Nieuwe Kaart van s’ Gravenhage 1833 Nouveau Plan De La Haije (HGA gr.0311) by city architect Zeger Reijers from 1833 and 1835 testifies to this. In the edge of a version from 1835, all monuments of the city are highlighted. The courtyards are not drawn, only the streets and squares with the monuments. All trees on the Voorhout, around the Vijverberg and along canals are individually indicatedper tree.

A few years later in the first issue of: Panorama van de Noordelijke Provinciën der Nederlanden, bevattende de schilderachtigste gezichten, kerken, hoofdgebouwen, gedenktekens, de belangrijkste straten en pleinen der steden, benevens de wandelingen in en om dezelve (1836) of the Van Lier brothers from The Hague. It also shook up the old city image as people liked it in The Hague, adistinguished village with huge pavilion houses in the ‘leafy green’ in the Hofkwartier, on Princen Plein and along the canals. However,this book turned out to be not only a retrospective but above all a program for the future: the period of the restoration of old values in the Netherlands, and in The Hague with its monuments.

For King Willem I, the triumvirate of mayor Lodewijk Constantijn Rabo Copes van Cattenburch (1771-1842), Secretary MarcellusEmants (1778-1854) and the city architect Zeger Reijers (1789-1857) took on the implementation of the representative parts of the city in the period 1824 and 1847. This depiction of the city by Zeger Reijers and the Van Lier brothers is rather suggestive, perhapseven misleading. There was no mention of the enormous war damage, the demolished houses, the slums on the outskirts of the city.In the years that followed, it was mainly conservative forces and students of Reijers who stuck to the beautification of the city andtried to keep Thorbecke’s liberal ideas at bay.

In 1840 Willem II (1792-1849) took over the kingship, but he died in 1849. A year before his death, the Constitution had been passedby Parliament in 1848 and the Municipal Act was introduced in 1851. During his reign, profound changes to the polity also took placeunder Thorbecke’s leadership. The state budget had taken on a worrying form after the Belgian uprising and the public debts hadbecome unmanageable. The power and influence of the Oranges was finally limited and fell to the national, provincial, and municipalgovernment.

The tension between the liberals who did not want government intervention and the conservatives who wanted to continue the line ofthe Oranges and especially the beautiful city was increased. The buildings of Willem I and II were still a collection of separatemonuments without any urban planning connection, as Zeger Reijers and the Van Lier brothers show. The buildings in neoclassicismmainly referred to Paris, where the architects of the Restoration were trained. Willem II opted for a different architecture. He washostile to the powerful club of court architects such as Reijers and the Hague Drawing Academy, who so benevolently designed allmonuments for his father. Neoclassicism had lost all the meaning associated with the Enlightenment and had become a slavishimitation of Parisian court culture.

The English-inspired architecture, of which Willem II was such a proponent, had taken on a different political and social significance atthat time, with Pugin and Barry as great examples. The image of this neo-Gothic architecture was used by Willem II, whose politicalpower was waning with the rise of the popular liberal Thorbecke. Willem II proceeded to purchase land around the city to realize hisambitions for palace clusters in the green. The Willemspark and the Willemshof were central to this. This iconic urban ensemblewould have a major influence on the urban development of The Hague. The Hague was on the eve of a huge urban development thatwould continue far beyond the canals.

The Willemshof 1838 and the Willemspark 1843

The Willemshof

With Willem II, the orientation shifted from Paris to London and Oxford. From individual monuments in the old city within the canals toa park courtyard outside the canals. In addition, the new king, and his consort Anna Paulowna (1795-1865), sister of the Russian tsar,brought the magnificent court culture to The Hague. Willem and Anna lived at Kneuterdijk Palace during the short reign from 1840 to1849. For his building plans, Willem II bought the Sorghvliet estate on 30 December 1837 and united it with his previously purchasedestates Hanenburg and Houtrust.

In the following years he bought the estates Buitenrust, Valkenbosch, Meerdervoort, Cranenburg and Rustenburg so that the RoyalDomain covered more than 600 hectares. They formed a contiguous area north and west of the city. His plan was to build theWillemshof near Sorghvliet (Goekoop, 1953). He did his own architectural work with his friend and adjutant Merkes van Gendt. Theking had all kinds of works carried out according to his own architectural ideas and plans, which did not exactly benefit thearchitectural quality. The king’s and hobby architect’s difficult dealings with The Hague architects contributed to the rapid decline ofhis own designed buildings (Ubels, 1966), (Blijstra, 1968).

For his most prestigious project, the Willemshof, he attracted the English architect Henry Ashton (1801-1872). Ashton had worked on the Windsor Palace, made improvements to Victoria Street, and designed some of the finest buildings on that street (Blijstra, 1968)(Van der Laarse, 2010). The Goekoop family, who would later buy the Catshuis, found in the attic with about twenty designs byAshton from the spring of 1838 for the Willemshof palace (Goekoop, 1953). In preparation for the construction activities for the Willemshof, Van der Spuij changed the course of the Haagse Beek. The old Beekmolen near the Zeestraat, which pumped the water from the Haagse Beek to the Hofvijver, had insufficient capacity (HGA gr.1028). At his own expense, the king had a steam pumpingstation built at Hanenburg and a canal built to lead the water from the Delftland bosom to the Haagse Beek. The flow of water on hisestates and in the city should start again (Goekoop, 1953), (Laarse, 2010). Van der Laarse claimed about the plans for the enormousneo-Gothic palace:

“[it] should, however, have become a very monumental palace complex by Dutch standards on the domain of the former Bentinckproperty Zorgvliet (the current Catshuis). Directly connected to the Binnenhof and its palaces in The Hague, this ‘Willemsparkhof’seemed intended in size, scale, and allure as a full-fledged counterpart to the great European parks of Versailles, Sanssouci(Potsdam), Schönbrunn (Vienna), and Windsor Castle.” (Van der Laarse, 2010: 174-175).

However, it remained with Ashton’s paper fantasies because the erratic client endlessly interfered with every detail. Van der Laarse(2010) further argued that the transition from neoclassicism to neo-Gothic in palace construction was mainly motivated by the positionof the Oranges in the European power play. Willem II’s plans must above all be seen in a European context. ‘[The] Hague plans, however, should have far exceeded this. Willem II’s ideal was to recreate The Hague, just like Brussels, as a city of culture. Despitehis earlier preference for the empire, his second building campaign in The Hague therefore seems to have been intended as a stylisticresponse to this court style continued in the South, of which his ‘looted’ Brussels palaces were rather a glorious symbol. He, the son-in-law of the Tsar of Russia and nephew of the King of Prussia, who above all wanted to be a different monarch from his authoritarianfather, now chose as head of state a neo-Gothic palace complex with a castellated character. Van der Laarse further argued that:

“It therefore seems certain that the Dutch Orange Prince wanted to compete with the European park courts with his constructioncampaigns in The Hague. However, the new national context after the Belgian Secession opposed a continuation of the neoclassicalpalace style. This was probably the reason why Willem II orientated himself on English neo-Gothic architecture, as it was mainly usedfor churches and garden buildings in the previous period. All over Europe, in this romantic period of cultural nation-building, the needfor a monumentalizing of one’s own past grew. The neo-Gothic glorified the newfound medieval prehistory and the chivalrous heroismof kingship.” (Van der Laarse, 2010: 178).

The European context certainly played an important role, but the social position of the king in a changing Dutch state system and in aturbulent period of Dutch and European history should not be overlooked.

Palace Quater

In addition to the park itself, it was also the surrounding buildings that partly determined the image. Between the palace cluster (Noordeinde, Kneuterdijk) and the Alexander barracks (1841/48) and the Alexanderplein (or field) where the cavalry did its exercises,the walking and riding park was started in 1843 with a riding school for Willem II. The old palaces on the Noordeinde and theKneuterdijk were connected by a combination of new intermediate buildings. In the garden of Kneuterdijk Palace the Gothic Hall wasbuilt and on the Noordeinde the Gothic Gallery, these were inaugurated in 1842, designed and executed by the architect G. Brouwer(Rosenberg, Vaillant & Valentijn, 1988) (HGA 0.51133).

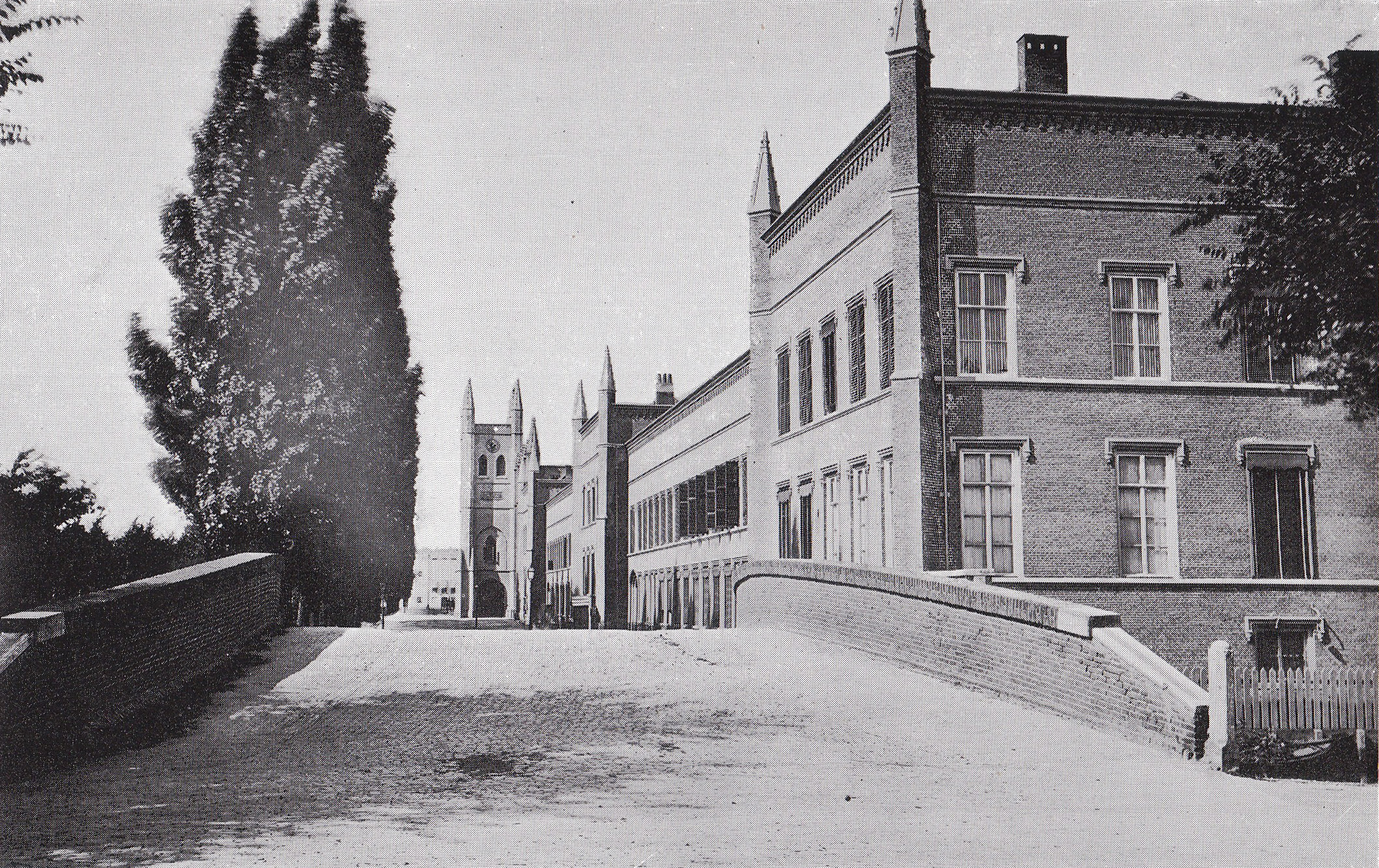

An impressive collection of paintings purchased by Willem II and originating from Brussels was housed here. With that park, onecontinuous green space was created from the Kneuterdijk to the Willemshof. Some streets were already partly built up, such as the Zeestraat, in the extension of the Noordeinde, which led to the village of Scheveningen. Where the Javastraat is now located, was atthe time a country road: the Laan van Schuddegeest, where the Alexanderveld was located with the barracks under construction inutilitarian architecture behind it. Here Hussars with horses were established, the cavalry that was part of the light cavalry. In 1875 the Third Regiment ’the Red Hussars’, later the ‘Court Regiment’ settled permanently in the Alexander barracks with 400 to 800 men andhorses. The Haagse Beek around the barracks was straightened and transformed into a system of canals and ditches. The architectwas Jhr. J.G.W. Merkes van Gendt, a colonel of engineers and aide-de-camp to Willem II. The barracks were demolished in 1971.

In the wake of the park construction, a fairy tale neo-Gothic urban bathhouse was built on the Zeestraat between 1842 and 1852, a castle-like building with towers and battlements. After only a few years, the building was replaced by luxury villas by the developer-architect Delia.

‘Au bon Marché’

In the year 1843, the Groote Koninklijke Bazar or Grand Bazar Royal (1843-1882-1927) (HGA kl.B 1723) was opened at Zeestraat80-82, a kind of department store museum for exotic products from all corners of Europe and the colonies. Probably the firstdepartment store appeared in Paris in 1851 ‘Au bon Marché’ and was a new concept where ‘small shops’ were merged into oneuncluttered space. Originally, the Bazar was a low-width one-story building with two naves, but in 1882 it was converted into an open and light building in an eclectic style with an open façade. Between the pilasters were wide shop windows where citizens couldadmire all the exotic merchandise of the world on the Sunday walk to Scheveningen. The entire building exuded the openness,freshness, and lightness of a warehouse. Gram (1906: 161-164) described the rise and fall of the bazaar, a building full of curiositiesand exotic wares. It was a combination of museum and shop in curiosities from Europe and the colonies. In 1927 this first bazaar inthe Willemspark was closed. The center of gravity had already shifted to the city center, where a variety of bazaars and warehouseswere built on the sites where seventeenth-century houses with workshops and shops once stood.

The riding school and barracks

Along the park on Nassaulaan, the architect Brouwer of Merkes van Gendt designed and built the riding school for the king in 1845, which also gave the park a wall on this side (HGA 5.24337). On the map of the Belinfante brothers, which was produced in 1845 andpublished two years later, there was no mention of the start of the park construction (HGA kl.0444). The new riding school was already signed as built and the construction of the Nassaustraat was in preparation, given the demarcation of the route. This streetwas exactly in line with the entrance of the Oranjekazerne so that a coherent urban ensemble was created between the two barracksand the park.

In 1846, houses for the officers of the Frederikskazerne were built next to the riding school on Nassaulaan, so that the wall wascompleted (HGA 0.49391). In 1862 a connection was made between the Laan van Schuddegeest (later called Javastraat) and theFrederikstraat. The three barracks were now easily accessible to each other and the street network around the park became morefine-meshed. After the death of Willem II in 1849, the buildings, gardens and parks of the Oranges were sold in 1855 and the parkpassed to the municipality. Already in 1863, the riding school was converted into a church by Saraber. The construction of the parkand the riding school resulted in a new building along the edges of the Zeestraat and later after 1857 also on the Javastraat and theMauritskade, but not in the neo-Gothic architecture of Willem II. The map of Ary van der Spuij, director of the private domains of KingWillem II, from 1857 showed the ensemble of the park, the riding school, the edge buildings with the bathhouse, the bazaar, and thebarracks in their original context (HGA gr.1028).

The Neo-Gothic Architecture of Willem II

Why did Willem II force a break with the Hague court architects of his father Willem I? Willem II was strongly oriented towardsEngland and was inspired for his neo-Gothic architecture, as in the Gothic Hall, by the Tudor hall in Christ Church College, Oxfordwhere he had studied (Blijstra, 1968). The soft yellow color of brick and sandstone of Willem II’s buildings seem to refer to Oxford, which was largely built with these materials and gives the city image its own unique atmosphere.

In the years before Willem II became king, in 1836-1837, the Houses of Parliament in London were built by the architects AugustusWelby Pugin (1812-1852) and Charles Barry (1795-1860). The work was a critique of Enlightenment rationalism and burgeoningindustrialization. It was also a critique of neoclassicism, the architecture of the Enlightenment, an architecture that also symbolizedthe Republic. Pugin recalled the ‘true ethos’ of the Middle Ages in north-western Europe where the monarch, like the church, stillstood among his subjects. In books such as: Contrasts (1836) and The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture (1841),Pugin described his social and architectural ideas in detail (Bank & Van Buuren, 2000: 155-164).

Pugin’s criticism did not mean abolishing the achievements of industrialization and capitalism, but he advocated a restoration of the long-lost medieval community ideal with a place for the sovereign. Early industrialization in England drove people apart and deprivedthem of historical awareness and awareness of the common origin. Especially in this troubled period of continuous uprisings in European cities and reform of the polity in the Netherlands under Thorbecke, the historical connection of the people with its monarchwas questioned by more and more people. Utensils reproduced as industrial mass products were signs of decline for Pugin (andpresumably also for Willem II). One had forgotten the authentic original of the product, just as one had forgotten the original societyfrom which one came. Pugin felt that the quality of the articles could be improved if they were designed and manufactured by artistsinstead of producing industrially, and thus endlessly repeating the original.

Pugin was supported by Henry Cole, who strongly encouraged the arts and crafts and helped organize the London World’s Fair in1851, where handicrafts from all over the world were exhibited. Cole’s pupil, Gottfried Semper had a major influence on architecturein the second half of the nineteenth century (including Berlage). Pugin, Cole and Semper did not reject industrialization but wanted toperfect it by restoring it by the artist’s hand and thus a common origin as it was assumed in the Middle Ages and the Gothic.

Seen in that light, the ideas of Pugin cum suis offered a perspective for both the Oranges and the people in the long run. GivenWillem II’s interest in art and England, it is certainly plausible that he was aware of the political and social significance of the Neo-Gothic in the sense of Pugin and Cole in architecture.

Only after the death of Willem II did another follower of Pugin’s ideas, John Ruskin, take a much more extreme position in his bookThe seven lamps of architecture (1849). He rejected all industrial products and use of machines and glorified craftsmanship andartistry. At the local level, the Oranges were sensitive to Roman Catholic emancipation, especially when the issue of the cemeterythat had been laid out in 1824 was high and the Catholics had to pay a toll to get to their final resting place. The Oranges supportedthe influential Catholic middle-class families in The Hague such as Drees, Peek, Krul, Smulders, Kaiser etc. (De Regt, 1986: 58-61).A few years earlier, the court architect Tollus had already built a chapel on the cemetery (1833/38).

The steam pumping station at Hanenburg

The construction of the expensive steam pumping station at Hanenburg and the canal of the Vliet there also showed that Willem IIhad an eye and nose for the needs of the city where the stagnant flow after raising the water level in 1825 saddled the city withstench, diseases, and death. A worthy monarch who imagined himself among his people had to intervene, even if it was symbolic.

In the year 1848 the Communist manifesto appeared and in February a revolution broke out in Paris because of the economicdepression and social unrest, which quickly spread to other European cities such as Vienna and Berlin. There were also fierceuprisings going on in The Hague, which were put down by the garrison. Willem II would die in March 1849 and be succeeded by hisless visionary son.

2.2 - The End of the Oranges' Interference

After 1948 and Thorbecke

In 1847, Manufacturing Department of The Hague was again placed under the control of a council committee. The triumvirate thatmanaged the manufacture and development of the city began to disintegrate as early as 1842 with the sudden death of the single-reigning Mayor Copes of Cattenburgh at City Hall. Three years later, in 1845, Emant’s resignation was requested due to his health and ayear later he was granted it. Now that Emants and Copes van Cattenburgh had disappeared, the Hague Council seized the opportunityto reorganize the Manufacturing Department of The Hague (Vijfvinkel, Campanje, Geus & Hegener, 1986).

They wanted a broad Commission of Fabrication, as it existed between 1816-24, with the city architect, the mayor, the municipalsecretary and two councilors. Reijers, who was able to determine his own policy until 1847, was now being reprimanded by thecommittee, which felt that he was making unnecessary expenditures. In 1848, the council significantly cut the budget of theManufacturing Department. Work was postponed and staff laid off. When purchasing material, it now had to be put out to public tender,which did not always benefit the quality of the material.

After the reorganization of 1848, the administrative basis was laid for a new Public Works Department. Every year in June, the department made an annual report indicating which embellishments and improvements needed to be discussed for the coming year.Reijers’ health left much to be desired, and he was assigned an assistant architect in 1852. Finally, after an application procedure inJanuary 1853, Van der Waeyen Pieterszen was appointed to assist him. Every year The Hague closed with a surplus but after 1853, after a reorganization of the municipal tax system because of the new municipal law, things went wrong: the city suddenly had muchless income. In 1857 the old master builder Reijers died.

On the advice of the college, his assistant Willem Cornelis van der Waeyen (or Waayen) Pieterszen (1819-1874) was appointed as hissuccessor. From 1857 to 1874 he would be the city architect of The Hague. After the death of Willem II in 1849, the Royal House with allthe estates and art that had been purchased appeared to be financially on the brink of collapse. The estate was a debt of four and a halfmillion guilders. The walking and riding park of Willem II (Willemspark) was sold to the municipality. The impressive art collection of theOranges was also sold. The riding school had already been sold and the Gothic Gallery along the Noordeinde was demolished in 1882due to dilapidation and the risk of collapse. The widow Anna Paulowna became the new owner of Sorghvliet. When she died atBuitenrust in 1866, Princess Sophie, Grand Duchess of Saxony, who normally stayed in Weimar, took possession of the estate.

Of all the buildings of Willem II, only the buildings on the Nassaulaan and the Gothic Hall behind the Kneuterdijk survived therenovations. After the accession of Willem III (1817-1890) in 1849, the Oranges would hardly exert any influence on the city image ofThe Hague. All that remained was the sale of royal possessions. Prince Alexander and his aunt Grand Duchess Sophia bought backKneuterdijk Palace and the Gothic Hall in a personal capacity. The garden of Kneuterdijk Palace, which extended all the way to theHooge Wal (the current Mauritskade), was sold to a pupil of Reijers, the architect Delia. After the death of Willem III, Kneuterdijk Palacewould remain the residence of Queen Regent Emma and her daughter Wilhelmina until 1940. The Oranges stayed from 1813 to 1940 inthe Noordeinde and Kneuterdijk palace cluster.

The Transformation from Private Park to Residential Park

The competition as a means of change

The Willemspark was transformed between 1857 and 1861 from a walking and driving park to a residential park. Separatemonuments and sub-plans were brought to a coherence with streets that made the houses accessible and emphasized the city imageof the leafy greenery, this time with luxury villas. With the purchase in the year 1855, the municipality wanted to transform the park into a residential park to increase the allure of the city.

One of the first plans for this was the building plan of the German architect Hermann Wentzel (1820-1889) from 1855 (HGA gr.1061). The court architect of Prince Frederik of the Netherlands. A plan that had been drawn up at the request of the municipal executive, but which was rejected by the city council on March 11, 1856. The buildings consisted of several spacious detached villas in a park-like environment.

Then the landscape architect J.D. Zocher (1791-1870) designed the park neighborhood in 1856, he had already shown what he was capable of based on a number of studies, but that design was not honored. The proposal differed quite a bit from the usual oeuvre of the Zochers and had a static and symmetrical design. Perhaps this design was by his son L.P. Zocher (1820-1915).

Eventually, the new city architect Cornelis van der Waeyen Pieterszen (1819-1874) designed the park. This was also a symmetrical design but now with an oval square instead of a round square. The street plan was also simpler, and the winding avenue had disappeared. Both designs followed the main structure of the existing park: an axis cross with a round point in the middle. Between 1857 and 1861, the municipality finally transformed the park into a luxury residential park, with the building plots being sold at a substantial profit.

The first photographs taken of the city around this period show young, planted trees in the residential park. Modern urban facilitiessuch as elevated sidewalks, drainage of streets with sewers and gas lanterns were immediately included in the design by Van derWaeyen Pieterszen and later in the surrounding streets such as Javastraat. In 1860, the surveyor Bevers drew a plan map of the Willemspark (HGA gr.1064) with the scale 1:2500, in which the plots, the buildings, the building heights and the height of the monument on the Plein 1813 were indicated.

On a series of wood engravings from 1860 in the The Hague Municipal Archive, the buildings were already drawn. Photos from the municipal archives showed that the young trees on Nassaustraat were already of some size around 1860 (HGA 0.49390). Theconnection between sub-plans and separate monuments of the Oranges was brought by Van der Waeyen Pieterszen. For the Hagueliberals in the new city council, the municipal development of the residential park was a painful defeat. In 1858, a council committeewas set up which concluded that private construction should be subject to as few regulations as possible (Stokvis 1987: 46).

In 1859 the result was a Algemeen Plan van Uitbouwing der Gemeente (General Plan of Development of the Municipality) by Van derWaeyen Pieterszen with expansion sketches for the Veenpolder in the following years with the Plan voor de uitbreiding van het N.W. gedeelte van ‘s-Gravenhage (Plan for the expansion of the north west part of ‘s-Gravenhage) (ca.1866) (HGA gr.1102), and the Stationsbuurt with the Plan van den Nieuwen Aanleg in het Zuidelijke gedeelte van ‘s-Gravenhage (Plan for the expansion of thesouthern part of ‘s-Gravenhage) (ca.1862/63) (HGA kl.1285 & kl.1286). In the end, only the parts were carried out on municipal land,just as they did with another municipal development at Oranjeplein (Stokvis, 1987: 46).

The iconic architects of the eclecticism

Eight architects and building contractors from The Hague bought the building plots in the Willemspark, designed, and built villas fortheir own account, which were resold. Beautiful mainly whitewashed villas by the architects Elie Saraber (1808-1878), JohannesJacobus Delia (1816-1898), Arend Roodenburg (1804-1884), Q. Wennekers, J.P.C. Swijser and Jansen (Blijstra, 1968: 36) were built in the park.

Only Delia used masonry in plain sight. The influence of Reijers’ students on the new generation of architects in The Hague wasgreat. The white colonial villas at Alexanderstraat 1 and 2 by Saraber with the green lawn along the Noordsingel and the wideverandas and balconies became a standard for residential park architecture. The beautiful brick mansions of Delia along the tree-lined avenues became a standard for the bourgeois neighborhoods that were built in the following years.

The rond-point Plein 1813 with its four stately houses and the grid structure of the Willemspark by the city architect Van der WaeyenPieterszen became the archetype for the squares and rigid grid street plans of the civilian neighborhoods that were built between1870 and 1890. Saraber, Delia, Roodenburg and Van der Waeyen Pieterszen were students of Reijers, educated at the HagueDrawing Academy Department of Architecture. The place where some of them would also become teachers themselves.

Plein 1813

The park consisted of Plein 1813 with four monumental white plastered villas, a monument in the middle and two intersectingmonumental axes, Alexanderstraat and Sophialaan and a ronds-point as was also in vogue in Paris. Furthermore, it was striking thatthe axes were not at an angle of 90 degrees to each other: there was an angular rotation. With this, Van der Waeyen Pieterszenseemed to anticipate the extension of the Sophialaan to a new urban interpretation in the ‘Kleine Veentje’ further away. TheSophialaan started at the riding school / church and ended with existing buildings in the Zeestraat. They hoped to buy properties thereand make a breakthrough to the new lay out of the city. The buildings in the Willemspark would also set the tone for the years thatfollowed. The Nassaustraat and Zeestraat were already built up.

For example, in the layout of the Zeeheldenkwartier and Archipelbuurt as shown on the maps Van der Waeyen Pieterszen & Last from 1868 (HGA z.gr.0025a), Van der Waeyen Pieterszen & Last from 1870 (HGA gr.0325)nand Van der Waeyen Pieterszen & Lastfrom 1879. Around 1860, the first blocks of mansions of Delia appeared on Alexanderstraat: Alexanderstraat 3-5, 4, 7-9-11, 8-10-12,13-15 and 14-16. The building at Plein 1813 no. 1 was also owned by Delia; this was the only white-plastered building of his hand.Two of the most iconic villas of the Willemspark were located on the corner of

The Alexanderstraat Axis, connecting the old and new centre of power

Alexanderstraat 1 and 2 and the canals and were designed by Saraber around 1860: white plastered villas with wide verandas thatoverlooked the lawn and the canal to the Mauritskade. There, at the same time as the development of the Willemspark, a contiguousblock of mansions was built by Delia on the corner of Mauritskade 19-33 with Parkstraat, ca. 1860. On the map of Lobatto from 1868buildings are drawn here (HGA z.gr.0024). There were also buildings on the other side of the Parkstraat. The council reports alsoshow that it belongs to Delia. Around the corner in the Parkstraat 109- 105 appeared another building block with three distinguishedmansions. These were also built around 1860 or perhaps a little later. In the wake of the development in the Willemspark, theconstruction of the Javastraat followed (after 1862/ 64). The residential building Javastraat 1a and 1c (1865) was also designed bythe architect Delia. Further on at Mauritskade 43-57 and Mauritskade 1-17, blocks of mansions with great architectural coherence andkinship appeared (Rosenberg, Vaillant & Valentijn, 1988: 67).

The Alexanderstraat axis was extended via the newly constructed Parkstraat, which took shape from 1859 and led to the LangeVoorhout. In 1862 Van der Waeyen Pieterszen drew the allotment for the Javastraat on the other side of the Willemspark on a scale of1: 2500. The seven very spacious lots were given a rhythm of protruding and backward buildings; the buildings in the axis of theAlexanderstraat jumped forward (HGA gr.1016). Jan Willem Arnold (1813-1885), who had become wealthy in the Indies, would havehis winter residence built there at Javastraat 26 between 1862 and 1864. On either side, the millionaire had three more buildings built, so that he owned Javastraat 20 to 32, almost all the lots that Van der Waeyen Pieterszen had drawn in 1862. The master builder isunknown. From 1910 to 1972, the council chamber would have been located here from where one could look from a widemonumental balcony over the Alexanderstraat and the Plein 1813, to the real center of power, the Lange Voorhout (De Regt, 1986).This axis would also become the new connection from the old city in the direction of the seaside resort of Scheveningen.

The Dutch Virgin of the Plein 1813

The competition in 1864 around the monument on the Plein 1813 gave rise to a serious conflict (Moll, 1954) (Blijstra, 1968). Twocamps emerged, one that supported the neoclassicism of the ‘Ebenhaëzer’ plan and one that supported the neo-Gothic ‘NO’. Asdescribed above, in both designs that remained, there was in any case no king worn or surrounded by his subjects on the pedestal, but the Dutch Virgin, symbol for the unity of the Dutch people and country. All designs with a king had already fallen off.

The first plan turned out to be by Koelman and Van der Waeyen Pieterszen, the second plan by Cuypers. There was a maincommittee of conservative industrialists who were staunch supporters of protectionism. In addition, there was a jury and anassessment committee. The division of labor was obviously not well organized. Ebenhaëzer won with 22 votes to 2 against the committee, however, the jury declared NO as the winner.

A fierce battle ensued in which all Dutch architects took sides for Ebenhaëzer. The architect Jan Leliman, secretary and laterchairman of the Society of Architecture (BNA) played an important role in this. The opposing party referred to important foreign greatssuch as Viollet le Duc, Labrouste, Garnier, Semper and Bötticher. Before Ebenhaëzer, Dutch greats such as government architectWillem Nicolaas Rose (1801-1877), who initially had doubts, were De Greef, Springer, Offenberg, Metzelaar, Bleijs, Eberson andGosschalk.

Eventually, Ebenhaëzer’s design was carried out, but the contradiction within the world of architects and society had become sharplyvisible. The controversy surrounding the competition for the monument on the Plein 1818 after 1863 symbolized the transition (Blijstra1968: 37-38). Proponents of the neoclassical design of J.P. Koelman and Van der Waeyen Pieterszen were diametrically opposed tothe proponents of neo-Gothic design: Pierre Cuypers (1827-1921). It was significant that in both designs there was no longer a kingon a pedestal but the Dutch Virgin as a symbol of National unity. The loser Cuypers would still be heard of in The Hague.

2.3 - The distinguished village in the leafy greenery

The iconic urban ensemble of Willemspark was mainly themed by the conservative forces that stood for a representative city image that people liked and that liberal forces in the city deeply regretted.

The theme neutral village in the leafy greenery stands like a house in The Hague. After 1860, The Hague would grow explosively andneighborhood after neighborhood would be laid out outside the canals. It was in this aftermath of the Oranges and the political upheavalthat the cityscape was themed by conservative and Orange-minded forces. The impetus for this was to be found in the unbridledambitions of Willem II with The Hague, of which hardly anything came to fruition. Under the Oranges, it remained only incidentalmonuments and parks.

The walking and riding park under Willem II was an island, the residential park after Willem II was embedded in a larger urbanensemble. Streets that connected all the new houses. The Lange Voorhout was connected with the Parkstraat and Plein 1813 with theJavastraat and thus a true avenue was created. The Plein 1813 should become the shining center of the series of squares of the civicquarters that were explained in the period that followed. Elsewhere in the city, the laid out of Oranjeplein had ended in failure becauselandowners did not want to cooperate.

Expropriation was not an option under Thorbecke. The city image organized by the municipality was a problem for liberals, after all:urban lay out was not a government task in their opinion. In the period from 1870 to 1890, the layout of neighborhoods became a matterfor private initiative. Until 1890, this field of tension would determine the urban lay out, resulting in three qualities of urban ensemble zones: luxury residential parks, civilian quarters, and working-class neighborhoods full of slums.

The city image of the beautiful city would mainly be extended to the residential parks and in a reduced version to the civilianneighborhoods, in the working-class neighborhoods only the sparse details in facades still remind of the bourgeois houses of Delia, leafygreenery was missing here.

Nowadays, the old city image of The Hague is experiencing a rebirth with a desire for climate adaptation and biodiversity in cities. Withcity architects from The Hague from the past such as Lindo, Berlage, Dudok and Van der Sluys and even with the layout of Ypenburg, one would always keep that city image in mind. That city image would prove to be a constant in The Hague’s DNA. In the comingchapters, the ideas of the urban planners mentioned will be discussed. Other city images are also highlighted and discussed, but the basic tone with all the other fragments of city images as islands would not change.